1.

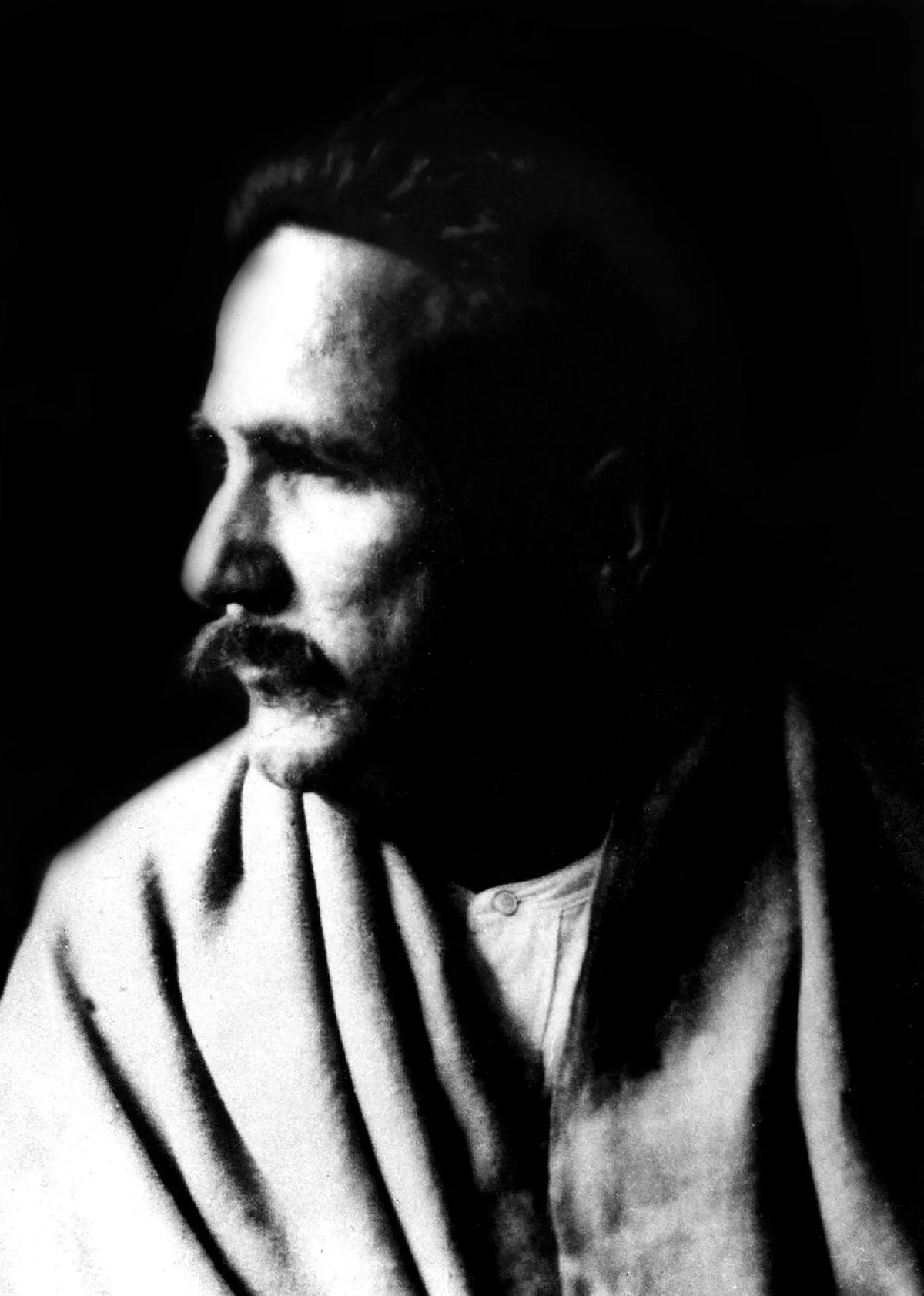

1. Sir Muhammad Iqbal was a South Asian Islamic philosopher, poet and politician.

1.

1. Sir Muhammad Iqbal was a South Asian Islamic philosopher, poet and politician.

Muhammad Iqbal's poetry is considered to be among the greatest of the 20th century, and his vision of a cultural and political ideal for the Muslims of British-ruled India is widely regarded as having animated the impulse for the Pakistan Movement.

Muhammad Iqbal taught Arabic at the Oriental College in Lahore from 1899 until 1903, during which time he wrote prolifically.

An ardent proponent of the political and spiritual revival of the Muslim world, particularly of the Muslims in the Indian subcontinent, the series of lectures Muhammad Iqbal delivered to this effect were published as The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam in 1930.

Muhammad Iqbal was elected to the Punjab Legislative Council in 1927 and held several positions in the All-India Muslim League.

Muhammad Iqbal was born on 9 November 1877 in a Punjabi-Kashmiri family from Sialkot in the Punjab Province of British India.

Muhammad Iqbal's family traced their ancestry back to the Sapru clan of Kashmiri Pandits who were from a south Kashmiri village in Kulgam and converted to Islam in the 15th century.

Muhammad Iqbal's mother-tongue was Punjabi, and he conversed mostly in Punjabi and Urdu in his daily life.

Muhammad Iqbal's grandfather was an eighth cousin of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, an important lawyer and freedom fighter who would eventually become an admirer of Muhammad Iqbal.

Muhammad Iqbal often mentioned and commemorated his Kashmiri lineage in his writings.

Muhammad Iqbal loved his mother, and on her death he expressed his feelings of pathos in an elegy:.

Muhammad Iqbal was four years old when he was sent to a mosque to receive instruction in reading the Qur'an.

Muhammad Iqbal learned the Arabic language from his teacher, Syed Mir Hassan, the head of the madrasa and professor of Arabic at Scotch Mission College in Sialkot, where he matriculated in 1893.

Muhammad Iqbal received an Intermediate level with the Faculty of Arts diploma in 1895.

Muhammad Iqbal was influenced by the teachings of Sir Thomas Arnold, his philosophy teacher at Government College Lahore, to pursue higher education in the West.

In 1907, Muhammad Iqbal moved to Germany to pursue his doctoral studies, and earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 4 November 1907.

Muhammad Iqbal preferred to write in this language because doing so made it easier to express his thoughts.

Muhammad Iqbal would write continuously in Persian throughout his life.

Muhammad Iqbal began his career as a reader of Arabic after completing his Master of Arts degree in 1899, at Oriental College and shortly afterward was selected as a junior professor of philosophy at Government College Lahore, where he had been a student in the past.

Muhammad Iqbal worked there until he left for England in 1905.

Muhammad Iqbal was profoundly influenced by Western philosophers such as Nietzsche, Bergson, and Goethe.

Muhammad Iqbal closely worked with Ibrahim Hisham during his stay at the Aligarh Muslim University.

Deeply grounded in religion since childhood, Muhammad Iqbal began concentrating intensely on the study of Islam, the culture and history of Islamic civilization and its political future, while embracing Rumi as "his guide".

Muhammad Iqbal's works focus on reminding his readers of the past glories of Islamic civilization and delivering the message of a pure, spiritual focus on Islam as a source for socio-political liberation and greatness.

Muhammad Iqbal denounced political divisions within and amongst Muslim nations, and frequently alluded to and spoke in terms of the global Muslim community or the Ummah.

Muhammad Iqbal's poetry was translated into many European languages in the early part of the 20th century.

Muhammad Iqbal was not only a prolific writer but a known advocate.

Muhammad Iqbal appeared before the Lahore High Court in both civil and criminal matters.

In 1933, after returning from a trip to Spain and Afghanistan, Muhammad Iqbal suffered from a mysterious throat illness.

Muhammad Iqbal spent his final years helping Chaudhry Niaz Ali Khan to establish the Dar ul Islam Trust Institute at a Jamalpur estate near Pathankot, where there were plans to subsidize studies in classical Islam and contemporary social science.

Muhammad Iqbal ceased practising law in 1934 and was granted a pension by the Nawab of Bhopal.

Muhammad Iqbal's tomb is located in Hazuri Bagh, the enclosed garden between the entrance of the Badshahi Mosque and the Lahore Fort, and official guards are provided by the Government of Pakistan.

Muhammad Iqbal first became interested in national affairs in his youth.

Muhammad Iqbal received considerable recognition from the Punjabi elite after his return from England in 1908, and he was closely associated with Mian Muhammad Shafi.

Muhammad Iqbal did not support Indian involvement in World War I and stayed in close touch with Muslim political leaders such as Mohammad Ali Jouhar and Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Muhammad Iqbal was a critic of the mainstream Indian National Congress, which he regarded as dominated by Hindus, and was disappointed with the League when, during the 1920s, it was absorbed in factional divides between the pro-British group led by Shafi and the centrist group led by Jinnah.

Muhammad Iqbal was active in the Khilafat Movement, and was among the founding fathers of Jamia Millia Islamia which was established at Aligarh in October 1920.

Muhammad Iqbal was given the offer of being the first vice-chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia by Mahatma Gandhi, which he refused.

In November 1926, with the encouragement of friends and supporters, Muhammad Iqbal contested the election for a seat in the Punjab Legislative Assembly from the Muslim district of Lahore, and defeated his opponent by a margin of 3,177 votes.

Muhammad Iqbal supported the constitutional proposals presented by Jinnah to guarantee Muslim political rights and influence in a coalition with the Congress and worked with Aga Khan and other Muslim leaders to mend the factional divisions and achieve unity in the Muslim League.

Ideologically separated from Congress Muslim leaders, Muhammad Iqbal had been disillusioned with the politicians of the Muslim League, owing to the factional conflict that plagued the League in the 1920s.

Discontent with factional leaders like Shafi and Fazl-ur-Rahman, Muhammad Iqbal came to believe that only Jinnah was a political leader capable of preserving unity and fulfilling the League's objectives of Muslim political empowerment.

Muhammad Iqbal firmly believed that Jinnah was the only leader capable of drawing Indian Muslims to the League and maintaining party unity before the British and the Congress:.

Muhammad Iqbal elucidated to Jinnah his vision of a separate Muslim state in a letter sent on 21 June 1937:.

Muhammad Iqbal, serving as president of the Punjab Muslim League, criticized Jinnah's political actions, including a political agreement with Punjabi leader Sikandar Hyat Khan, whom Muhammad Iqbal saw as a representative of feudal classes and not committed to Islam as the core political philosophy.

Nevertheless, Muhammad Iqbal worked constantly to encourage Muslim leaders and masses to support Jinnah and the League.

Madani's position throughout was to insist on the Islamic legitimacy of embracing a culturally plural, secular democracy as the best and the only realistic future for India's Muslims where Muhammad Iqbal insisted on a religiously defined, homogeneous Muslim society.

Madani and Muhammad Iqbal both appreciated this point and they never advocated the creation of an absolute 'Islamic State'.

Muhammad Iqbal expressed fears that not only would secularism weaken the spiritual foundations of Islam and Muslim society but that India's Hindu-majority population would crowd out Muslim heritage, culture, and political influence.

Ambedkar, Muhammad Iqbal expressed his desire to see Indian provinces as autonomous units under the direct control of the British government and with no central Indian government.

Muhammad Iqbal was elected president of the Muslim League in 1930 at its session in Allahabad in the United Provinces, as well as for the session in Lahore in 1932.

The latter part of Muhammad Iqbal's life was concentrated on political activity.

Muhammad Iqbal travelled across Europe and West Asia to garner political and financial support for the League.

Muhammad Iqbal reiterated the ideas of his 1932 address, and, during the third Round Table Conference, he opposed the Congress and proposals for transfer of power without considerable autonomy for Muslim provinces.

Muhammad Iqbal would serve as president of the Punjab Muslim League, and would deliver speeches and publish articles in an attempt to rally Muslims across India as a single political entity.

Muhammad Iqbal consistently criticized feudal classes in Punjab as well as Muslim politicians opposed to the League.

Muhammad Iqbal was the first patron of Tolu-e-Islam, a historical, political, religious and cultural journal of the Muslims of British India.

Muhammad Iqbal asserts that an individual can never aspire to higher dimensions unless he learns of the nature of spirituality.

In "Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed", Muhammad Iqbal first poses questions, then answers them with the help of ancient and modern insight.

Muhammad Iqbal depicts himself as Zinda Rud guided by Rumi, "the master", through various heavens and spheres and has the honour of approaching divinity and coming in contact with divine illuminations.

Again, Muhammad Iqbal depicts Rumi as a character and gives an exposition of the mysteries of Islamic laws and Sufi perceptions.

Muhammad Iqbal's The Call of the Marching Bell, his first collection of Urdu poetry, was published in 1924.

The second set of poems date from 1905 to 1908, when Muhammad Iqbal studied in Europe, and dwell upon the nature of European society, which he emphasised had lost spiritual and religious values.

Muhammad Iqbal urges the entire Muslim community, addressed as the Ummah, to define personal, social and political existence by the values and teachings of Islam.

Muhammad Iqbal's works were in Persian for most of his career, but after 1930 his works were mainly in Urdu.

Muhammad Iqbal wrote two books, The Development of Metaphysics in Persia and The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, and many letters in the English language.

Muhammad Iqbal wrote a book on Economics that is rare.

Muhammad Iqbal discussed philosophy, God and the meaning of prayer, human spirit and Muslim culture, as well as other political, social and religious problems.

Muhammad Iqbal was invited to Cambridge to participate in a conference in 1931, where he expressed his views, including those on the separation of church and state, to students and other participants:.

Muhammad Iqbal wrote some poems in Punjabi, such as "Piyaara Jedi" and "Baba Bakri Wala", which he penned in 1929 on the occasion of his son Javed's birthday.

Muhammad Iqbal has been referred to as the "Poet of the East" by academics, institutions and the media.

The Vice-Chancellor of Quaid-e-Azam University, Dr Masoom Yasinzai, stated in a seminar addressing a distinguished gathering of educators and intellectuals that Muhammad Iqbal is not only a poet of the East but is a universal poet.

Yet it should be borne in mind that while dedicating his Eastern Divan to Goethe, the cultural icon par excellence, Muhammad Iqbal's Payam-i-Mashriq constituted both a reply as well as a corrective to the Western Divan of Goethe.

For by stylizing himself as the representative of the East, Muhammad Iqbal endeavored to talk on equal terms to Goethe as the representative of West.

Muhammad Iqbal thought that Muslims had long been suppressed by the colonial enlargement and growth of the West.

Muhammad Iqbal is called Muffakir-e-Pakistan and Hakeem-ul-Ummat.

In Iran, Muhammad Iqbal is known as Muhammad Iqbal-e Lahori.

Muhammad Iqbal was not acquainted with Persian idiom, as he spoke Urdu at home and talked to his friends in Urdu or English.

Muhammad Iqbal did not know the rules of Persian prose writing.

Muhammad Iqbal highly praised the work of Iqbal in Persian.

An example of the admiration and appreciation of Iran for Muhammad Iqbal is that he received the place of honour in the pantheon of the Persian elegy writers.

Muhammad Iqbal became even more popular in Iran in the 1970s.

Muhammad Iqbal's verses appeared on banners, and his poetry was recited at meetings of intellectuals.

Muhammad Iqbal inspired many intellectuals, including Ali Shariati, Mehdi Bazargan and Abdulkarim Soroush.

Muhammad Iqbal has an audience in the Arab world, and in Egypt one of his poems has been sung by Umm Kulthum, the most famous modern Egyptian artist, while among his modern admirers there are influential literary figures such as Farouk Shousha.

In Saudi Arabia, among the important personalities who were influenced by Muhammad Iqbal there was Abdullah bin Faisal Al Saud, a member of the Saudi royal family and himself a poet.

Critics of Abbot's viewpoint note that Muhammad Iqbal was raised and educated in the European way of life, and spent enough time there to grasp the general concepts of Western civilization.

Muhammad Iqbal is widely commemorated in Pakistan, where he is regarded as the ideological founder of the state.

The Government of Madhya Pradesh in India awards the Muhammad Iqbal Samman, named in honour of the poet, every year at the Bharat Bhavan to Indian writers for their contributions to Urdu literature and poetry.

The Pakistani government and public organizations have sponsored the establishment of educational institutions, colleges, and schools dedicated to Muhammad Iqbal and have established the Muhammad Iqbal Academy Pakistan to research, teach and preserve his works, literature and philosophy.

Muhammad Iqbal's son Javed Iqbal served as a justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.