1.

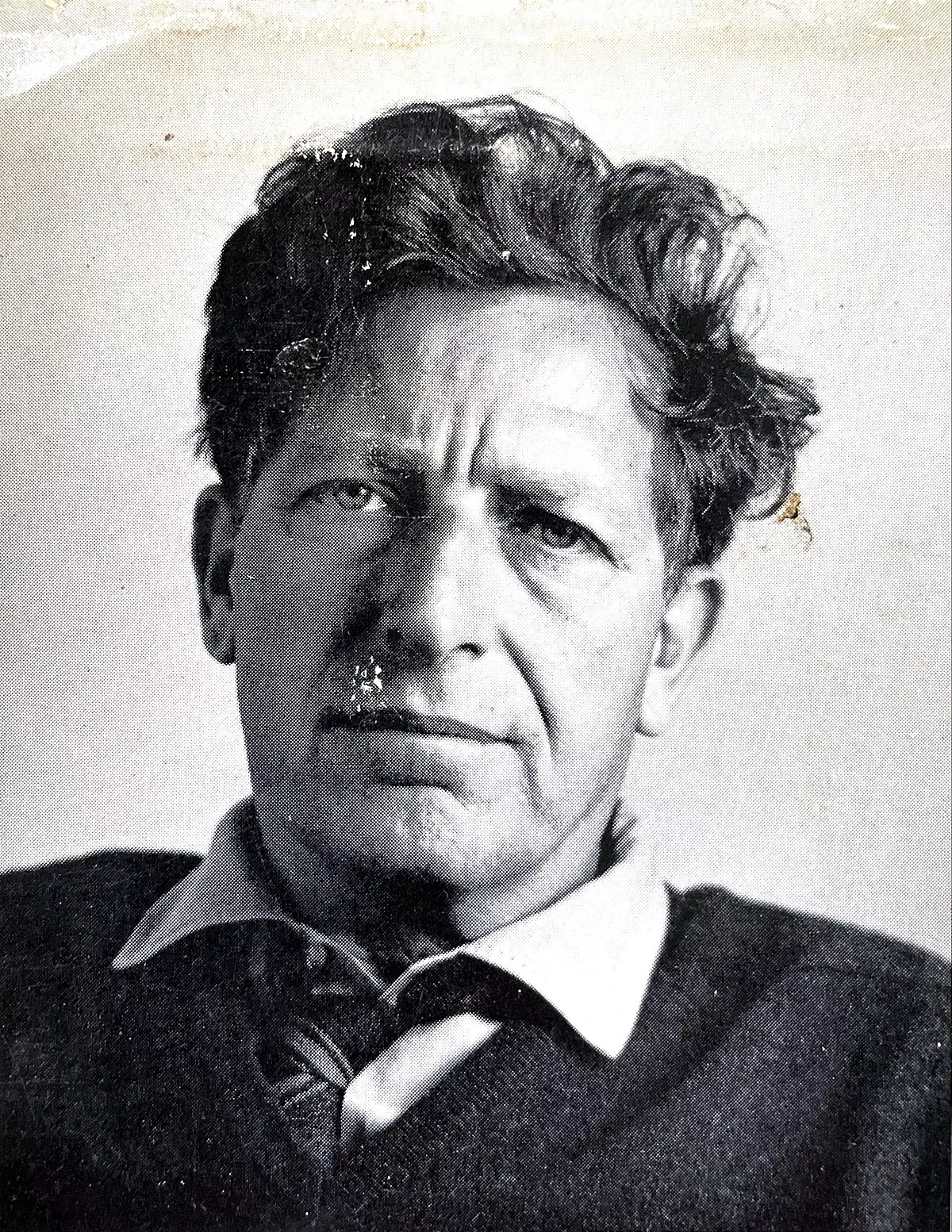

1. Paul Goodman was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism.

1.

1. Paul Goodman was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism.

Paul Goodman returned to writing in New York City and took sporadic magazine writing and teaching jobs, several of which he lost for his overt bisexuality and World War II draft resistance.

Paul Goodman co-wrote the theory behind Gestalt therapy based on Wilhelm Reich's radical Freudianism and held psychoanalytic sessions through the 1950s while continuing to write prolifically.

Paul Goodman became known as "the philosopher of the New Left" and his anarchistic disposition was influential in 1960s counterculture and the free school movement.

Paul Goodman is remembered for his utopian proposals and principled belief in human potential.

Paul Goodman was born in New York City on September 9,1911, to Augusta and Barnette Paul Goodman.

Paul Goodman's grandfather had fought in the American Civil War and the family was "relatively prosperous".

Paul Goodman attended Hebrew school and the city's public schools, where he excelled and developed a strong affinity with Manhattan.

Paul Goodman performed well in literature and languages during his time at Townsend Harris Hall High School and graduated atop his class in 1927.

Paul Goodman started at City College of New York the same year, where he studied classical literature, majored in philosophy, was influenced by philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen, and found both lifelong friends and his intellectual social circle.

Paul Goodman came to identify with "community anarchism" since reading Peter Kropotkin as an undergraduate, and kept the affiliation throughout his life.

Paul Goodman graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1931, early in the Great Depression.

Paul Goodman did not keep a regular job, but read scripts for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and taught drama at a Zionist youth camp during the summers 1934 through 1936.

Unable to afford tuition, Paul Goodman audited graduate classes at Columbia University and traveled to some classes at Harvard University.

When Columbia philosophy professor Richard McKeon moved to the University of Chicago, he invited Paul Goodman to attend and lecture.

Between 1936 and 1940, Paul Goodman was a graduate student in literature and philosophy, a research assistant, and part-time instructor.

Homesick and absent his doctorate, Paul Goodman returned to writing in New York City, where he was affiliated with the literary avant-garde.

Paul Goodman worked on his dissertation, though it would take 14 years to publish.

Paul Goodman taught at Manumit, a progressive boarding school, in 1943 and 1944, but was let go for "homosexual behavior".

In 1945, Paul Goodman started a second common-law marriage that would last until his death.

Fritz and Lore Perls contacted Paul Goodman after reading his writing on Reich and began a friendship that yielded the Gestalt therapy movement.

Paul Goodman authored the theoretical chapter of their co-written Gestalt Therapy.

Paul Goodman continued in this occupation through 1960, taking patients, running groups, and leading classes at the Gestalt Therapy Institutes.

Paul Goodman spent 1948 and 1949 writing in New York and published The Break-Up of Our Camp, a short story collection, followed by two novels: the 1950 The Dead of Spring and the 1951 Parents' Day.

Paul Goodman returned to his writing and therapy practice in New York City in 1951 and received his Ph.

Mid-decade, Paul Goodman entered a life crisis when publishers did not want his epic novel The Empire City, a new lay therapist licensing law excluded Paul Goodman, and his daughter contracted polio.

Paul Goodman embarked to Europe in 1958 where, through reflections on American social ills and respect for Swiss patriotism, Goodman became zealously concerned with improving America.

Paul Goodman read the founding fathers and resolved to write patriotic social criticism that would appeal to his fellow citizens rather than criticize from the sidelines.

Paul Goodman's work had brought little money or fame up to this point.

Paul Goodman proposed alternatives in topics across the humanist spectrum from family, school, and work, through media, political activism, psychotherapy, quality of life, racial justice, and religion.

In contrast to contemporaneous mores, Paul Goodman praised traditional, simple values, such as honor, faith, and vocation, and the humanist history of art and heroes as providing hope for a more meaningful society.

Paul Goodman spoke regularly on college campuses, discussing tactics with students, and seeking to cultivate youth movements, such as Students for a Democratic Society and the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, that would take up his political message.

Paul Goodman became known both as the movement's philosopher and as "the philosopher of the New Left".

Paul Goodman continued to publish at least a book a year for the rest of his life, including critiques of education, a treatise on decentralization, a "memoir-novel", and collections of poetry, sketch stories, and previous articles.

Paul Goodman produced a collection of critical broadcasts he had given in Canada as Like a Conquered Province.

Paul Goodman was the Washington Institute for Policy Studies's first visiting scholar before serving multiple semester-long university appointments in New York, London, and Hawaii.

Paul Goodman, who enjoyed polemics, was undeterred by their words but dispirited by the movement's turn towards insurrectionary politics.

Paul Goodman's health worsened due to a heart condition, and he died of a heart attack at his farm in North Stratford, New Hampshire, on August 2,1972, at the age of 60.

Paul Goodman's prose has, at times, been commonly criticized for its sloppiness or impenetrability.

Paul Goodman believed that humans were inherently creative, communal, and loving, except when societal institutions alienate individuals from their natural selves, such as making them suppress their impulses to serve the institution.

Paul Goodman's oeuvre addressed humanism broadly across multiple disciplines and sociopolitical topics including the arts, civil planning, civil rights and liberties, decentralization and self-regulation, democracy, education, ethics, media, technology, "return to the land", war, and peace.

Paul Goodman was prolific in sharing specific ideas for improving society to match his aims, and actively advocated for them in frequent lectures, letters, op-eds, and media appearances.

Paul Goodman resolved to write positively, patriotically, and accessibly about reform for a larger audience rather than simply resisting conformity and "drawing the line" between himself and societal pressures.

Paul Goodman was most famous as a political thinker and social critic.

Paul Goodman rejected grand schemes to reorganize the world and instead argued for decentralized counter-institutions across society to downscale societal organization into small, community-based units that better served immediate needs.

Paul Goodman blamed political centralization and a power elite for withering populism and creating a "psychology of powerlessness".

Paul Goodman advocated for alternative systems of order that eschewed "top-down direction, standard rules, and extrinsic rewards like salary and status".

Paul Goodman often referenced classical republican ideology, such as improvised, local political decision-making and principles like honor and craftsmanship.

Paul Goodman believed that one's duty as a citizen, nevertheless as a student or faculty member, was to take politcal stances.

Civil liberty, to Paul Goodman, was less about freedom from coercive institutions, as commonly articulated in anarchist politics, and more about freedom to initiate within a community, as is necessary for the community's continued evolution.

Love and the creative rivalry of fraternity, wrote Paul Goodman, is what spurs the individual initiative to do what none could do alone.

Paul Goodman praised classless, everyday, democratic values associated with American frontier culture.

Paul Goodman was interested in radicalism native to the United States, such as populism and Randolph Bourne's anarcho-pacifism, and distanced himself from Marxism and European radicalism.

Paul Goodman is associated with the New York Intellectuals circle of college-educated, secular Jews, despite his political differences with the group.

Paul Goodman criticized the intellectuals as having first sold out to Communism and then to the "organized system".

Paul Goodman's role as a New York Intellectual cultural figure was satirized alongside his coterie in Delmore Schwartz's The World Is a Wedding and namechecked in Woody Allen's Annie Hall.

Paul Goodman's radicalism was based in psychological theory, his views on which evolved throughout his life.

Paul Goodman first adopted radical Freudianism based in fixed human instincts and the politics of Wilhelm Reich.

Paul Goodman believed that natural human instinct served to help humans resist alienation, advertising, propaganda, and will to conform.

Paul Goodman moved away from Reichian individualistic id psychology towards a view of the nonconforming self integrated with society.

Third, as a follower of Kant, Paul Goodman believed in the self as a synthesized combination of internal human nature and the external world.

Unlike the silent Freudian analyst, Paul Goodman played an active, confrontational role as therapist.

Paul Goodman believed his role was less to cure sickness than to adjust clients to their realities in accordance with their own desires by revealing their blocked potential.

The therapist, to Paul Goodman, should act as a "fellow citizen" with a responsibility to reflect the shared, societal sources of these blockages.

Paul Goodman invokes "human nature" as multifaceted and unearthed by new culture, institutions, and proposals.

Paul Goodman offers no common definition of "human nature" and suggests that no common definition is needed even when claiming that some action is "against human nature".

Paul Goodman contends that humans are animals with tendencies and that a "human nature" forms between the human and an environment he deems suitable: a continually reinvented "free" society with a culture developed from and for the search for human powers.

Paul Goodman saw himself as continuing the work started by John Dewey.

Paul Goodman figured that "natural" human development has similar aims, which is to say that education and "growing up" are identical.

Paul Goodman contended that a lack of community, patriotism, and honor stunts the normal development of human nature and leads to "resigned or fatalistic" youth.

Paul Goodman argues that the busyness of American high schools and extracurricular activities preclude students from developing their individual interests, and that students should spend years away from schooling before working towards a liberal arts college degree.

Paul Goodman believes in dismantling large educational institutions to create small college federations and "alternative colleges" that promoted direct relations between faculty and students.

Paul Goodman was encouraged by the free university movement's initiative, as students actively pursued their genuine interests outside the traditional academic constraints of credits and requirements.

Paul Goodman was discouraged when students did not express as much interest as he had in the Western tradition.

Paul Goodman valued what he called the provincial virtues of the country's national character, such as dutifulness, frugality, honesty, prudence, and self-reliance.

Paul Goodman valued curiosity, lust, and willingness to break rules for self-evident good.

Paul Goodman was married to Virginia Miller between 1938 and 1943.

Between 1945 and his death, Paul Goodman was married to Sally Duchsten.

Paul Goodman was fired from his teaching position there for not taking his cruising off-campus.

Paul Goodman was known for his paradoxical identity and contrarian stances.

Paul Goodman believed in liberating coalitions but broke from black power and gay rights movements or coalitions whose collective power diminished individual autonomy.

Paul Goodman loved to shock and his aggressive, cunning argumentative style tended towards polemics and explaining both how his interlocutor was completely wrong and from which basics they should begin anew.

Paul Goodman's unmannered physical presence was a core piece of his presentation and idiosyncratic celebrity as a social gadfly, partly since Paul Goodman himself championed a lack of separation between public and private lives.

Dwight Macdonald said that Paul Goodman did not have close relationships with his intellectual equals and was more personable with his younger admirers and disciples.

Paul Goodman lamented how "Goodman was always taken for granted even by his admirers", praised his literary breadth, and predicted that his poetry would eventually find widespread appreciation.

Some of Paul Goodman's ideas have been assimilated into mainstream thought: local community autonomy and decentralization, better balance between rural and urban life, morality-led technological advances, break-up of regimented schooling, art in mass media, and a culture less focused on a wasteful standard of living.

Paul Goodman bridged the 1950s era of mass conformity and repression into the 1960s era of youth counterculture in his encouragement of dissent.

Paul Goodman influenced many of the late 1960s critics of education, including George Dennison, John Holt, Ivan Illich, and Everett Reimer.