1.

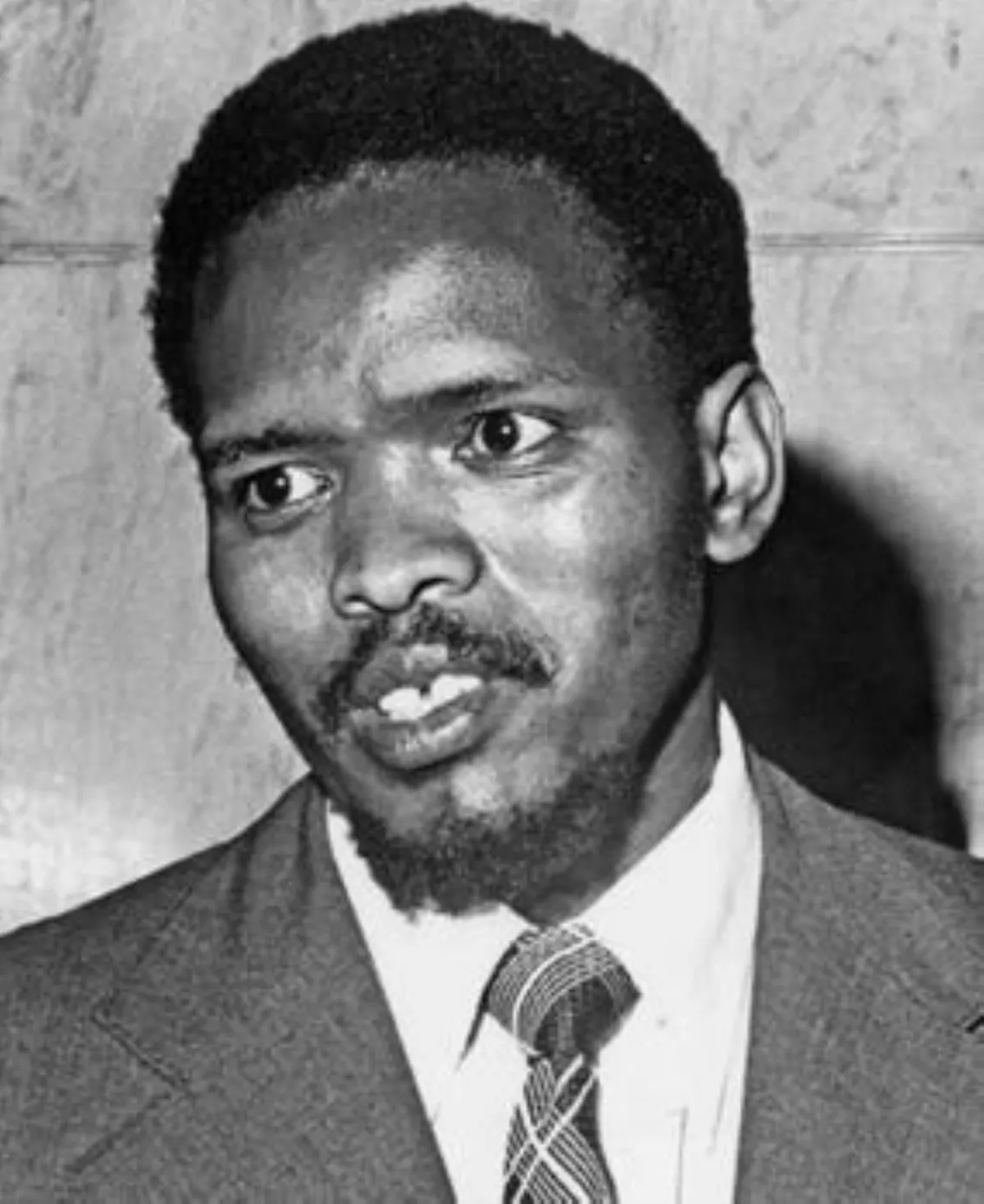

1. Bantu Stephen Biko OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid activist.

1.

1. Bantu Stephen Biko OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid activist.

Steve Biko's ideas were articulated in a series of articles published under the pseudonym Frank Talk.

Strongly opposed to the apartheid system of racial segregation and white-minority rule in South Africa, Steve Biko was frustrated that NUSAS and other anti-apartheid groups were dominated by white liberals, rather than by the blacks who were most affected by apartheid.

Steve Biko believed that well-intentioned white liberals failed to comprehend the black experience and often acted in a paternalistic manner.

Steve Biko developed the view that to avoid white domination, black people had to organise independently, and to this end he became a leading figure in the creation of the South African Students' Organisation in 1968.

Steve Biko was careful to keep his movement independent of white liberals, but opposed anti-white hatred and had white friends.

Steve Biko believed that black people needed to rid themselves of any sense of racial inferiority, an idea he expressed by popularizing the slogan "black is beautiful".

Steve Biko remained politically active, helping organise BCPs such as a healthcare centre and a creche in the Ginsberg area.

Steve Biko became the subject of numerous songs and works of art, while a 1978 biography by his friend Donald Woods formed the basis for the 1987 film Cry Freedom.

Nonetheless, Steve Biko became one of the earliest icons of the movement against apartheid, and is regarded as a political martyr and the "Father of Black Consciousness".

Bantu Stephen Steve Biko was born on 18 December 1946, at his grandmother's house in Tarkastad, Eastern Cape.

Steve Biko's parents had married in Whittlesea, where his father worked as a police officer.

Steve Biko was raised in his family's Anglican Christian faith.

In 1950, when Steve Biko was four, his father fell ill, was hospitalised in St Matthew's Hospital, Keiskammahoek, and died, making the family dependent on his mother's income.

Steve Biko spent two years at St Andrews Primary School and four at Charles Morgan Higher Primary School, both in Ginsberg.

Steve Biko excelled at maths and English and topped the class in his exams.

From 1964 to 1965, Steve Biko studied at St Francis College, a Catholic boarding school in Mariannhill, Natal.

The college had a liberal political culture, and Steve Biko developed his political consciousness there.

Steve Biko became particularly interested in the replacement of South Africa's white minority government with an administration that represented the country's black majority.

Steve Biko later said that most of the "politicos" in his family were sympathetic to the PAC, which had anti-communist and African racialist ideas.

Steve Biko admired what he described as the PAC's "terribly good organisation" and the courage of many of its members, but he remained unconvinced by its racially exclusionary approach, believing that members of all racial groups should unite against the government.

Steve Biko was initially interested in studying law at university, but many of those around him discouraged this, believing that law was too closely intertwined with political activism.

Steve Biko secured a scholarship, and in 1966 entered the University of Natal Medical School.

The late 1960s was the heyday of radical student politics across the world, as reflected in the protests of 1968, and Steve Biko was eager to involve himself in this environment.

Steve Biko later related that this event forced him to rethink his belief in the multi-racial approach to political activism:.

Steve Biko developed SASO's ideology of "Black Consciousness" in conversation with other black student leaders.

Steve Biko believed that, as part of the struggle against apartheid and white-minority rule, blacks should affirm their own humanity by regarding themselves as worthy of freedom and its attendant responsibilities.

Steve Biko presented a paper on "White Racism and Black Consciousness" at an academic conference in the University of Cape Town's Abe Bailey Centre in January 1971.

Steve Biko expanded on his ideas in a column written for the SASO Newsletter under the pseudonym "Frank Talk".

Steve Biko stepped down from the presidency after a year, insisting that it was necessary for a new leadership to emerge and thus avoid any cult of personality forming around him.

Steve Biko argued that NUSAS merely sought to influence the white electorate; in his opinion, this electorate was not legitimate, and protests targeting a particular policy would be ineffective for the ultimate aim of dismantling the apartheid state.

In Durban, Steve Biko entered a relationship with a nurse, Nontsikelelo "Ntsiki" Mashalaba; they married at the King William's Town magistrates court in December 1970.

Steve Biko initially did well in his university studies, but his grades declined as he devoted increasing time to political activism.

Steve Biko voted in favour of the group's creation but expressed reservations about the lack of consultation with South Africa's Coloureds or Indians.

In September 1972, Steve Biko visited Kimberley, where he met the PAC founder and anti-apartheid activist Robert Sobukwe.

Steve Biko's banning order in 1973 prevented him from working officially for the BCPs from which he had previously earned a small stipend, but he helped to set up a new BPC branch in Ginsberg, which held its first meeting in the church of a sympathetic white clergyman, David Russell.

Steve Biko helped to revive the Ginsberg creche, a daycare for children of working mothers, and establish a Ginsberg education fund to raise bursaries for promising local students.

Steve Biko helped establish Njwaxa Home Industries, a leather goods company providing jobs for local women.

Steve Biko disagreed with this action, correctly predicting that the government would use it to crack down on the BCM.

Steve Biko was called as a witness for the defence; he sought to refute the state's accusations by outlining the movement's aims and development.

In 1973, Steve Biko had enrolled for a law degree by correspondence from the University of South Africa.

Steve Biko passed several exams, but had not completed the degree at his time of death.

Steve Biko hoped to convince Woods to give the movement greater coverage and an outlet for its views.

Steve Biko acknowledged that his earlier "antiliberal" writings were "overkill", but said that he remained committed to the basic message contained within them.

Steve Biko remained friends with another prominent white liberal, Duncan Innes, who served as NUSAS President in 1969; Innes later commented that Steve Biko was "invaluable in helping me to understand black oppression, not only socially and politically, but psychologically and intellectually".

In 1977, Steve Biko broke his banning order by travelling to Cape Town, hoping to meet Unity Movement leader Neville Alexander and deal with growing dissent in the Western Cape branch of the BCM, which was dominated by Marxists like Johnny Issel.

Steve Biko was arrested for having violated the order restricting him to King William's Town.

The police later said that Steve Biko had attacked one of them with a chair, forcing them to subdue him and place him in handcuffs and leg irons.

Steve Biko was examined by a doctor, Ivor Lang, who stated that there was no evidence of injury on Steve Biko.

Steve Biko was then examined by two other doctors who, after a test showed blood cells to have entered Biko's spinal fluid, agreed that he should be transported to a prison hospital in Pretoria.

Steve Biko was the twenty-first person to die in a South African prison in twelve months, and the forty-sixth political detainee to die during interrogation since the government introduced laws permitting imprisonment without trial in 1963.

News of Steve Biko's death spread quickly across the world, and became symbolic of the abuses of the apartheid system.

Steve Biko's death attracted more global attention than he had ever attained during his lifetime.

Steve Biko's coffin had been decorated with the motifs of a clenched black fist, the African continent, and the statement "One Azania, One Nation"; Azania was the name that many activists wanted South Africa to adopt post-apartheid.

Steve Biko's account was challenged by some of Biko's friends, including Woods, who said that Biko had told them that he would never kill himself in prison.

Publicly, he stated that Steve Biko had been plotting violence, a claim repeated in the pro-government press.

The security forces alleged that Steve Biko had acted aggressively and had sustained his injuries in a scuffle, in which he had banged his head against the cell wall.

The failure of the government-employed doctors to diagnose or treat Steve Biko's injuries has been frequently cited as an example of a repressive state influencing medical practitioners' decisions, and Steve Biko's death as evidence of the need for doctors to serve the needs of patients before those of the state.

In December 1998, the Commission refused amnesty to the five men; this was because their accounts were conflicting and thus deemed untruthful, and because Steve Biko's killing had no clear political motive, but seemed to have been motivated by "ill-will or spite".

Steve Biko was influenced by his reading of authors like Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Leopold Sedar Senghor, James Cone, and Paulo Freire.

Steve Biko rejected the apartheid government's division of South Africa's population into "whites" and "non-whites", a distinction that was marked on signs and buildings throughout the country.

Steve Biko was not a Marxist and believed that it was oppression based on race, rather than class, which would be the main political motivation for change in South Africa.

Steve Biko is first of all oppressed by an external world through institutionalised machinery and through laws that restrict him from doing certain things, through heavy work conditions, through poor pay, through difficult living conditions, through poor education, these are all external to him.

Steve Biko saw white racism in South Africa as the totality of the white power structure.

Steve Biko argued that under apartheid, white people not only participated in the oppression of black people but were the main voices in opposition to that oppression.

Steve Biko thus argued that in dominating both the apartheid system and the anti-apartheid movement, white people totally controlled the political arena, leaving black people marginalised.

Steve Biko believed white people were able to dominate the anti-apartheid movement because of their access to resources, education, and privilege.

Steve Biko nevertheless thought that white South Africans were poorly suited to this role because they had not personally experienced the oppression that their black counterparts faced.

Steve Biko believed that blacks needed to affirm their own humanity by overcoming their fears and believing themselves worthy of freedom and its attendant responsibilities.

Steve Biko defined Black Consciousness as "an inward-looking process" that would "infuse people with pride and dignity".

Steve Biko opposed any collaboration with the apartheid government, such as the agreements that the Coloured and Indian communities made with the regime.

Steve Biko openly criticised the Zulu leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi, stating that the latter's co-operation with the South African government "[diluted] the cause" of black liberation.

Steve Biko believed that those fighting apartheid in South Africa should link with anti-colonial struggles elsewhere in the world and with activists in the global African diaspora combating racial prejudice and discrimination.

Steve Biko hoped that foreign countries would boycott South Africa's economy.

Steve Biko believed that while apartheid and white-minority rule continued, "sporadic outbursts" of violence against the white minority were inevitable.

Steve Biko wanted to avoid violence, stating that "if at all possible, we want the revolution to be peaceful and reconciliatory".

Steve Biko was suspicious of the Soviet Union's motives in supporting African liberation movements, relating that "Russia is as imperialistic as America", although he acknowledged that "in the eyes of the Third World they have a cleaner slate".

Steve Biko acknowledged that the material assistance provided by the Soviets was "more valuable" to the anti-apartheid cause than the "speeches and wrist-slapping" provided by Western governments.

Steve Biko was cautious of the possibility of a post-apartheid South Africa getting caught up in the imperialist Cold War rivalries of the United States and the Soviet Union.

Steve Biko hoped that a future socialist South Africa could become a completely non-racial society, with people of all ethnic backgrounds living peacefully together in a "joint culture" that combined the best of all communities.

Steve Biko did not support guarantees of minority rights, believing that doing so would continue to recognise divisions along racial lines.

Steve Biko saw individual liberty as desirable, but regarded it as a lesser priority than access to food, employment, and social security.

Black, said Steve Biko, is not a colour; Black is an experience.

Steve Biko believed that, if post-apartheid South Africa remained capitalist, some black people would join the bourgeoisie but inequality and poverty would remain.

Steve Biko stated that this would require an education of the black population in order to teach them how to live in a non-racial society.

Tall and slim in his youth, by his twenties Steve Biko was over six feet tall, with the "bulky build of a heavyweight boxer carrying more weight than when in peak condition", according to Woods.

Steve Biko's friends regarded him as "handsome, fearless, a brilliant thinker".

Steve Biko had from an early age the unmistakable bearing and quality of a unique leader.

Steve Biko owned few clothes and dressed in a low-key manner.

Steve Biko had a large record collection and particularly liked gumba.

Steve Biko enjoyed parties, and according to his biographer Linda Wilson, he often drank substantial quantities of alcohol.

Steve Biko was often critical of the established Christian churches, but remained a believer in God and found meaning in the Gospels.

Mangcu noted that Steve Biko was critical of organised religion and denominationalism and that he was "at best an unconventional Christian".

Steve Biko displayed no racial prejudice, sleeping with both black and white women.

Steve Biko's wife chose the name Nkosinathi, and Steve Biko named their second child after the Mozambican revolutionary leader Samora Machel.

Steve Biko was in a relationship with Lorrain Tabane; they had a child named Motlatsi in 1977.

Steve Biko is viewed as the "father" of the Black Consciousness Movement and the anti-apartheid movement's first icon.

Some academics argue that Steve Biko's thought remains relevant; for example, in African Identities in 2015, Isaac Kamola wrote that Steve Biko's critique of white liberalism was relevant to situations like the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals and Invisible Children, Inc.

Woods held the view that Steve Biko had filled the vacuum within the country's African nationalist movement that arose in the late 1960s following the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela and the banning of Sobukwe.

Followers of Steve Biko's ideas re-organised as the Azanian People's Organisation, which subsequently split into the Socialist Party of Azania and the Black People's Convention.

The defence that Biko provided for arrested SASO activists was used as the basis for the 1978 book The Testimony of Steve Biko, edited by Millard Arnold.

The South African government banned many books about Steve Biko, including those of Arnold and Woods.

Steve Biko's death inspired several songs, including from artists outside South Africa such as Tom Paxton and Peter Hammill.

The English singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel released "Steve Biko" in tribute to him, which was a hit single in 1980, and was banned in South Africa soon after.

In Salvador, Bahia, a Steve Biko Institute was established to promote educational attainment among poor Afro-Brazilians.

In 1994, the ANC issued a campaign poster suggesting that Steve Biko had been a member of their party, which was untrue.