1.

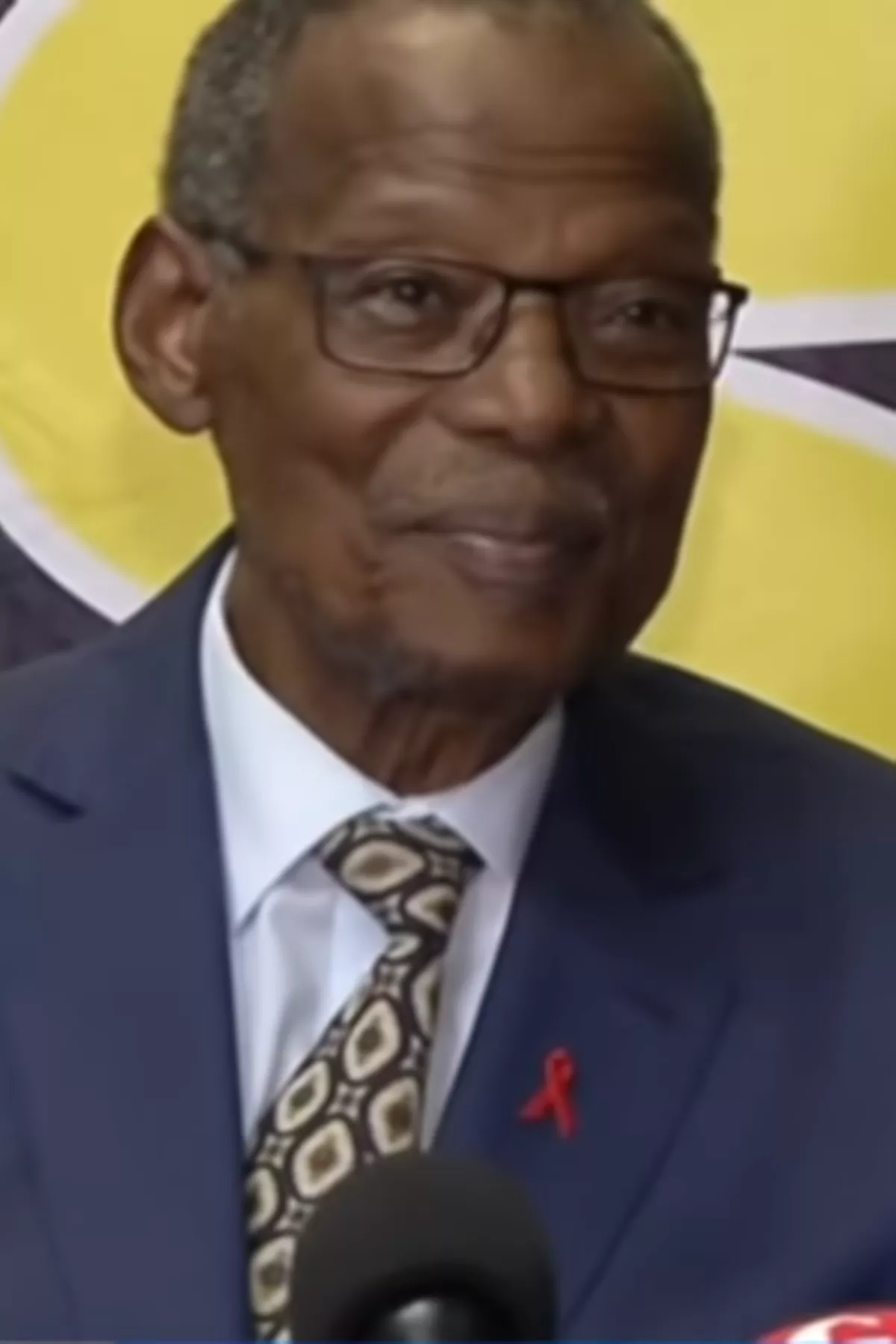

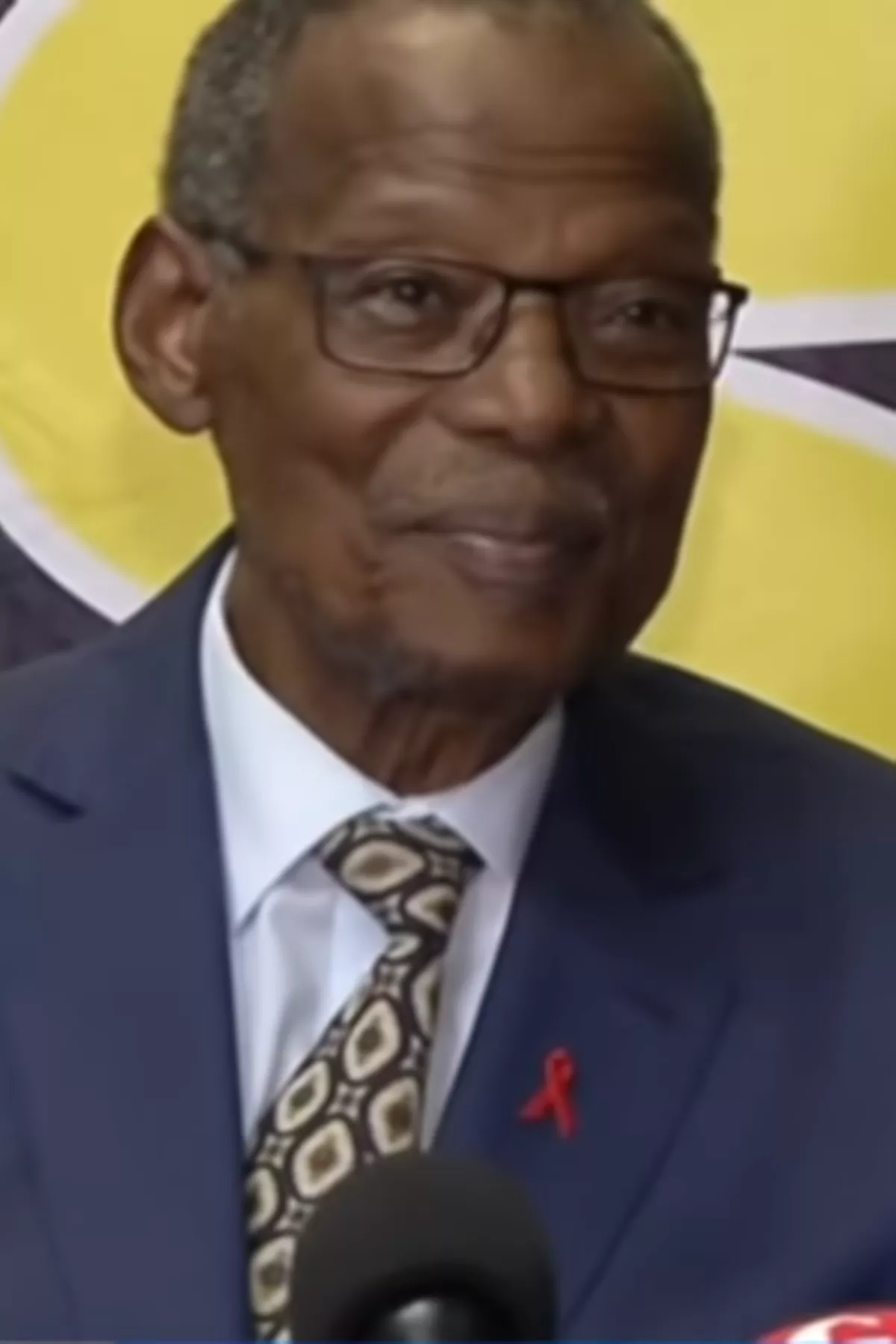

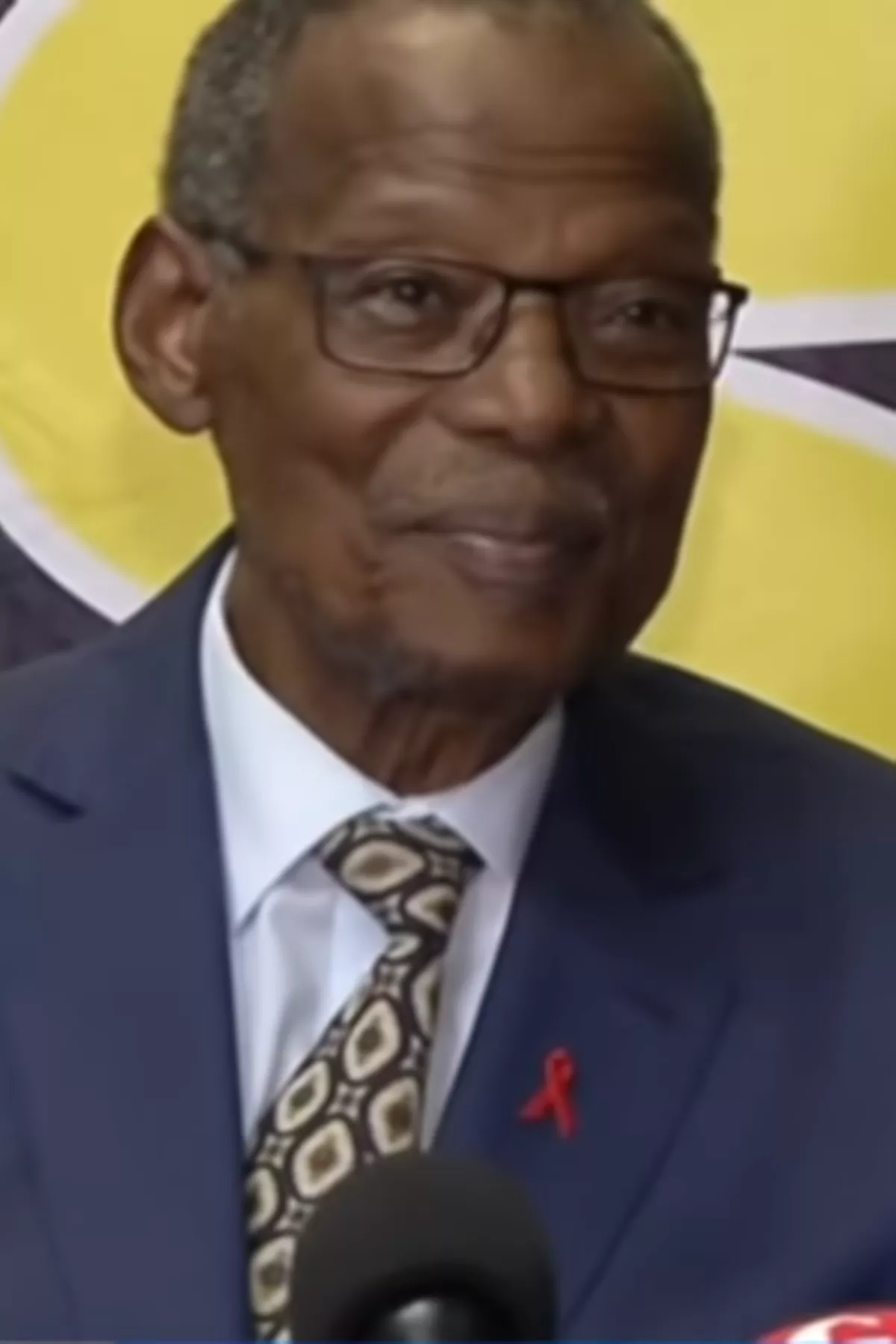

1. Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was a South African politician and Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023.

1.

1. Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was a South African politician and Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was appointed to this post by King Bhekuzulu, the son of King Solomon kaDinuzulu.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was a political leader during Nelson Mandela's incarceration and continued to be so in the post-apartheid era, when he was appointed by Mandela as Minister of Home Affairs, serving from 1994 to 2004.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was one of the most prominent black politicians of the apartheid era.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was the sole political leader of the KwaZulu government, entering when it was still the native reserve of Zululand in 1970 and remaining in office until it was abolished in 1994.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was himself born into the Zulu royal family; his maternal grandfather was King Dinuzulu who was a son of King Cetshwayo and whom Buthelezi played in the 1964 film called Zulu.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi lobbied consistently for the release of Nelson Mandela and staunchly refused to accept the nominal independence which the government offered to KwaZulu, correctly judging that it was a superficial independence.

However, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was derided in some quarters for participating in the bantustan system, a central pillar of apartheid, and for his moderate stance on such issues as free markets, armed struggle, and international sanctions.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi became a bete noire of young activists in the Black Consciousness Movement and was repudiated by many in the African National Congress.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi played a complicated role during the negotiations to end apartheid, for which he helped set the framework as early as 1974 with the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi established the Concerned South Africans Group with other conservatives, withdrew from the negotiations, and launched a boycott of the 1994 general election, South Africa's first under universal suffrage.

However, despite fears that Mangosuthu Buthelezi would upend the peaceful transition entirely, Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the IFP relented soon before the election, and not only participated, but joined the Government of National Unity formed afterwards by newly elected President Mandela.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi served as Minister of Home Affairs under Mandela and under his successor, Thabo Mbeki, despite near-continuous tensions between the IFP and the governing ANC.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi remained the IFP's president until the party's 35th National General Conference in August 2019, when he declined to seek re-election and was succeeded by Velenkosini Hlabisa.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was the oldest MP in his country at the time of his death in 2023.

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was born on 27 August 1928, at Ceza Swedish Missionary Hospital in Mahlabathini in southeastern Natal.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's mother was Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu, the daughter of former Zulu King Dinuzulu and sister of the incumbent King Solomon kaDinuzulu.

Mathole Mangosuthu Buthelezi was a traditional leader as chief of the Mangosuthu Buthelezi clan and his marriage to the princess was arranged by King Solomon to heal a rift between the clan and the royal family.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi is sometimes referred to by his clan name, Shenge, used as an honorific.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was educated at Impumalanga Primary School at Mahashini in Nongoma from 1935 to 1943, then at Adams College, a famous mission school in Amanzimtoti, from 1944 to 1946.

In 1948, the National Party was elected to government in South Africa and began implementing a formal system of apartheid, and Mangosuthu Buthelezi joined the anti-apartheid African National Congress Youth League in 1949.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi made much of his association with Pixley ka Isaka Seme, a founder of the ANC, who was married to his mother's half-sister.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi counted Seme, Albert Luthuli, and Mahatma Gandhi as among his political influences; he was inspired by Martin Luther King's leadership of the American civil rights movement.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was expelled from Fort Hare in 1950 for participating in a student boycott during a visit to the campus of Gideon Brand Van Zyl, the Governor-General.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi later completed his Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Natal and worked as a clerk in the government's Department of Native Affairs in Durban.

In 1953, Mangosuthu Buthelezi returned to Mahlabathini to become chief of the Mangosuthu Buthelezi clan, a hereditary position and lifetime appointment.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi later recounted how Luthuli had persuaded him not to "betray my people and seek my own selfish ends away from them".

Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that his mother had encouraged him to take up the role.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi acted in the 1964 film Zulu, about the Battle of Rorke's Drift, playing the role of his real-life great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo kaMpande.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was reappointed by Cyprian's successor, King Goodwill Zwelithini, in 1968.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi pointed in particular to his paternal great-grandfather, Mnyamana, who was a senior advisor to his maternal great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo, during the Anglo-Zulu War, and claimed that his father was appointed traditional prime minister to his uncle, King Solomon, in 1925.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's supporters sometimes claim instead that Nqengelele was a senior advisor "alongside Ngomane".

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was rumoured to have been estranged from the royal family from 1968 to 1970, as his status as traditional prime minister came into question.

Under this new system, Mangosuthu Buthelezi became head of the executive branch as the Chief Executive Councillor of KwaZulu; his title was changed to Chief Minister in February 1977 when the territory was declared fully "self-governing" and its government was granted additional powers.

The 1972 KwaZulu constitution vested all executive powers in Mangosuthu Buthelezi and granted the Zulu king a largely ceremonial role, requiring him to "hold himself aloof from party politics and sectionalism".

On some accounts, it was during this struggle that Mangosuthu Buthelezi began to appeal to his family's tradition of providing traditional prime ministers, seeking to establish a claim to the premiership.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded the Inkatha National Cultural Liberation Movement at KwaNzimela outside Melmoth on 21 March 1975 and became its first president.

Formally, and as Mangosuthu Buthelezi often insisted, Inkatha was not a sectional party but a national movement open to all black South Africans; in practice its members were almost all Zulus from the KwaZulu region.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi argues that "Zulus," a social construct that has been anything but constant over time, should have a separate political dispensation, that its members have certain unique personality traits, that an insult directed at that identity deserves retribution, and that its survival justifies conflict with other organizations and individuals.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi remained Inkatha's sole president throughout apartheid and for more than two decades afterwards.

The Alliance initially comprised Inkatha, the Labour Party, and the Indian Reform Party; Mangosuthu Buthelezi was elected its chairman.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was not only chief minister but finance minister, and became police minister in 1980 when the KwaZulu Police was established.

However, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was instrumental in setting up teacher training and nursing colleges throughout the late-1970s and the early-1980s.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi argued that the apartheid government intended to use the land deal to extend South African influence in Swaziland; it would have allowed Swaziland to act as a conservative buffer state between South Africa and the left-wing, pro-ANC Frontline State of Mozambique.

Observers pointed out that it would advance the apartheid policy of stripping black South Africans of South African citizenship and that it could be a form of retaliation against Mangosuthu Buthelezi for refusing to accept KwaZulu independence.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi held popular demonstrations against the deal, lobbied the Organisation of African Unity for support, and challenged the plan four successive times in court.

In 2022 a statue of Mangosuthu Buthelezi was erected in Jozini, Ingwavuma, to commemorate his role.

The value and sincerity of Mangosuthu Buthelezi's contribution to the anti-apartheid struggle was a highly polarising issue inside South Africa during apartheid and remains controversial.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu famously asked Mangosuthu Buthelezi to leave the funeral of Robert Sobukwe in 1978 because supporters of the Pan Africanist Movement objected fiercely to his presence, throwing stones at him and calling him a "sell-out" and "government stooge".

Indeed, historian Stephen Ellis wrote that, perhaps excepting Bantu Holomisa, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was "more successful than any other homeland leader in asserting his own autonomy" against the apartheid state.

Also in 1971, in a column for the Rand Daily Mail entitled "End This Master-Servant Relationship", Mangosuthu Buthelezi called on the central government to provide KwaZulu with more land and resources, arguing:.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's critics submit that the delays were designed to give him time to sideline monarchist leaders who might otherwise have sought to unseat him.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi reminded people that Seme and John Dube had been involved in Inkatha's predecessor movement, founded by his uncle.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's view was that the ANC had not sufficiently supported and guided Inkatha after 1975 and that Buthelezi was the ANC's "fault".

Mangosuthu Buthelezi had responded by criticising the exiled ANC in turn.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded in 1986 a conservative trade union, the United Workers Union of South Africa, allied with Inkatha, to counter the growing influence of the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi has claimed that his rejection of violence and sanctions caused the party to turn against him.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi has voiced his frustrations with the effectiveness of Nelson Mandela himself.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was a big proponent in advocating for the release of Mandela but was disappointed with his effectiveness in brokering peace and ending violence in South Africa.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi deviated from the orthodoxy of the anti-apartheid movement in ways other than his involvement in the homeland system.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi opposed the armed struggle and the student protests, consumer boycotts, and union strikes that dominated grassroots anti-apartheid organising in that period under the United Democratic Front.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi developed a lifelong friendship with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

However, Mangosuthu Buthelezi rejected the 1983 Constitution introduced by the NP to establish the Tricameral Parliament, believing, as other activists did, that the political reforms it introduced were insufficient.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi campaigned for a "no" vote in the 1983 constitutional referendum alongside Frederik van Zyl Slabbert of the Progressive Federal Party and other liberals.

In 1986, for example, Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that Botha "has got his head so deeply buried in the sand that you will have to recognize him by the shape of his shoes", and he refused to meet with Botha for five years after Botha was impolite to him in a meeting.

For some ANC leaders, their most significant gripe with Mangosuthu Buthelezi was the perception that he had ordered, sanctioned, or allowed the ongoing political violence in KwaZulu, Natal, and the Transvaal between Inkatha supporters and groups aligned to the ANC and broader Congress movement, including the UDF.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's alleged involvement in political violence is the primary concern of some of his harshest contemporary critics, such as City Press editor Mondli Makhanya.

At the time, Mangosuthu Buthelezi blamed the ANC for the violence; he still did in 2019.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that he had never endorsed violence and that he could not control any "high-ranking members of Inkatha who have been involved in acts of violence in their local situations"; but the New York Times noted that his public statements about the violence were "calculatedly ambiguous".

Mangosuthu Buthelezi reportedly approached the state for help training Inkatha protection units for Inkatha leaders, himself among them, who were explicitly or implicitly threatened by political rivals, including the ANC and UDF.

The Commission found that Mangosuthu Buthelezi had been personally involved in planning the operation, as had General Magnus Malan; it concluded that President Botha and the State Security Council had been aware of the scheme.

The codename of the operation, Marion, was derived from the word marionette and related terms, suggesting that Mangosuthu Buthelezi was seen as the state's marionette.

On 4 January 1974 in Mahlabatini, Mangosuthu Buthelezi signed the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith with Harry Schwarz, the Transvaal leader of the United Party, then South Africa's official parliamentary opposition.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi later said that, once founded, Inkatha subscribed to the principles set out in the Mahlabtini Declaration.

From 1991 to 1993, Mangosuthu Buthelezi led the IFP's delegation to the multi-party constitutional negotiations at the Congress for a Democratic South Africa and Multi-Party Negotiating Forum, although he personally boycotted CODESA sessions in protest of the steering committee's decision not to allow a separate delegation representing King Zwelithini.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was furious that the IFP had been excluded from the agreement.

The week before the election, Mangosuthu Buthelezi announced that he had agreed to accept their proposal after negotiations by Kenyan diplomat Washington Okumu.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that after the election he was swayed by the majority view in his party: "As a democrat I do what my people want, even if I don't like it".

Mandela appointed Mangosuthu Buthelezi acting president more than a dozen times in periods when both he and his deputy, Thabo Mbeki, were abroad.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi deployed the South African National Defence Force across the border to protect Pakalitha Mosisili's government, inaugurating a months-long military incursion by South Africa.

When Zwelithini invited Mandela to a traditional Shaka Day commemoration service, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was angered that he had not been consulted; IFP supporters stormed the royal palace, disrupting a visit by Mandela, and Mangosuthu Buthelezi organised a boycott of Zwelithini's annual Reed Dance.

That weekend, Mangosuthu Buthelezi presided over Shaka Day services held without the king for the first time ever; in his speech, he surprised observers by rejecting the concept of a sovereign Zulu state with an executive monarch.

Zulu had been in the middle of an appearance on a live television interview programme and had been criticising Mangosuthu Buthelezi; Mangosuthu Buthelezi happened to be in the same building for a different interview, had watched Zulu's remarks on a monitor, and had stormed uninvited onto the chat show's set with his bodyguards to confront Zulu, not realising that the cameras were still rolling.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was widely criticised, including for transgressing the values of freedom of speech and freedom of the press, and the following day he issued a public apology to the programme's viewers.

In December 1994, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was appointed chairperson of the new KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders; his appointment was challenged by Zwelithini.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi saw the appointment as continuous with his earlier role in the province, but Zwelithini continued to insist that he was not and had never been traditional prime minister.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi therefore retained the Home Affairs portfolio for another term.

Mbeki had offered him the position of deputy president, but on the condition that the IFP would help elect an ANC representative as Premier of KwaZulu-Natal; Mangosuthu Buthelezi was unwilling to meet this condition.

Mbeki later said that he initially offered the deputy presidency unconditionally, but had been persuaded by his party to link it to the KwaZulu-Natal government; he said that Mangosuthu Buthelezi, likewise, had been persuaded not to accept the proposal by his party, who would view it as "dishonourable" and as elevating Mangosuthu Buthelezi personally at the expense of his organisation.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi appointed Buthelezi as chairperson of two of the six cabinet committees.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi continued to deny that he had ever "ordered, ratified or condoned human rights violations" and launched a lengthy legal battle to force the Commission to open its records to him and change its report.

The existing immigration regulations had been suspended in March 2003 after the Cape High Court ruled that Mangosuthu Buthelezi had not followed proper public consultation procedures when devising them; he published the new regulations in haste because of a court application lodged by an impatient citizen.

Mbeki and Maduna applied for the court to declare the regulations invalid and void, and there was a comical exchange of press releases in which Maduna's department declared that the regulations would not be implemented just as Mangosuthu Buthelezi's department declared that they would be.

The judge found no grounds to believe that Mangosuthu Buthelezi had been deceitful but agreed with Mbeki that the regulations required collective cabinet approval; they were set aside.

In 2007, Mangosuthu Buthelezi reflected of the incident, "I am not aware of any world precedent in which a president not only sued his own minister, but went so far as trying to get a cost order against him in his personal capacity".

The KwaZulu-Natal Traditional Leadership and Governance Act of 2005 further entrenched the status of the KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders as an advisory body attached to the KwaZulu-Natal provincial legislature with the power to make non-binding recommendations about legislation related to traditional leadership and governance; Mangosuthu Buthelezi remained its chairperson.

Sources told News24 that the document had been well received by the parliamentary caucus when first tabled in a meeting in which Mangosuthu Buthelezi was not present, but that Mangosuthu Buthelezi had been "livid" about the report and in a subsequent caucus meeting had read from a prepared statement attacking "the author of the document" without naming Woods.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi told the press that he felt Woods had "mis-assessed the situation in the party"; Woods himself released a statement in which he said that the media had misrepresented the report and overstated the extent to which it blamed Buthelezi for the party's problems.

The KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders was up for re-election in the same period, but Mangosuthu Buthelezi withdrew ahead of the vote, saying that he would not stand for re-election as chairperson.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's withdrawal followed an announcement by the Independent Electoral Commission which suggested that he was not the frontrunner for the position: Bhekisisa Bhengu had received 28 nominations against Buthelezi's 24.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi claimed that ANC leaders, including newly elected President Zuma and Premier Zweli Mkhize, had induced traditional leaders to withdraw their support for him in exchange for bribes.

The IFP was due to convene a national elective conference, in July 2009, to elect its leadership, but the conference was postponed indefinitely; Mangosuthu Buthelezi's critics, especially in the Youth Brigade, said that it was a delaying tactic intended to buy his supporters time to shore up his re-election as IFP president.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was re-elected unopposed as IFP president, but the conference signalled the beginning of a leadership succession process by amending the party's constitution to create a deputy president post; Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that he would stay on to oversee a "smooth transition".

On 20 January 2019, Mangosuthu Buthelezi announced that he would not seek re-election to another term as party president of the IFP, pointing out that he had been intending to step down since 2006.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was intimately involved in negotiating the battle and on multiple occasions his critics within the royal house accused him of exceeding his authority.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi married Irene Audrey Thandekile Mzila, whom he met at a wedding in January 1949 when she was a nursing student from Johannesburg.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi said that he was occasionally put under pressure to take on additional wives, in line with customary Zulu polygamy, but had followed Christian edicts in remaining monogamous.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's traditional residence was at kwaPhindangene in Ulundi in northern KwaZulu-Natal, and he was a fan of classical and choral music.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi contracted COVID-19 twice, in August 2020 and December 2021, and was hospitalised with hypertension in January 2022.

On 1 August 2023, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was reportedly hospitalised due to back problems.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi's funeral was attended by prominent politicians and royalties including EFF leader Julius Malema and his former deputy Floyd Shivambu; UDM president Bantu Holomisa; former presidents Thabo Mbeki, Kgalema Motlanthe, and Jacob Zuma; Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria and President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was buried at a family cemetery next to his house in Kwaphindangene later that same day.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was succeeded as head of the clan by his son Zuzifa Buthelezi.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was made a Knight Commander of the Star of Africa for Outstanding Leadership by Liberian President William Tolbert in 1975 and appointed to the French National Order of Merit in 1981; King Goodwill Zwelithini awarded him the King's Cross Award in 1989 and the King Shaka Gold Medal in 2001.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi has been awarded four honorary doctorates in law, from the University of Zululand in 1976, the University of Cape Town in 1978, Florida's Tampa University in 1985, and Boston University in 1986.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was named Man of the Year by the Institute of Management Consultants in 1972 and by the Financial Mail in 1985, and Newsmaker of the Year by the South African Society of Journalists in 1973 and Pretoria Press Club in 1985.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was patron of the Mangosuthu University of Technology and is a former Chancellor of the University of Zululand, a ceremonial position to which he was appointed in 1979; he was the first black person to hold the title.