1.

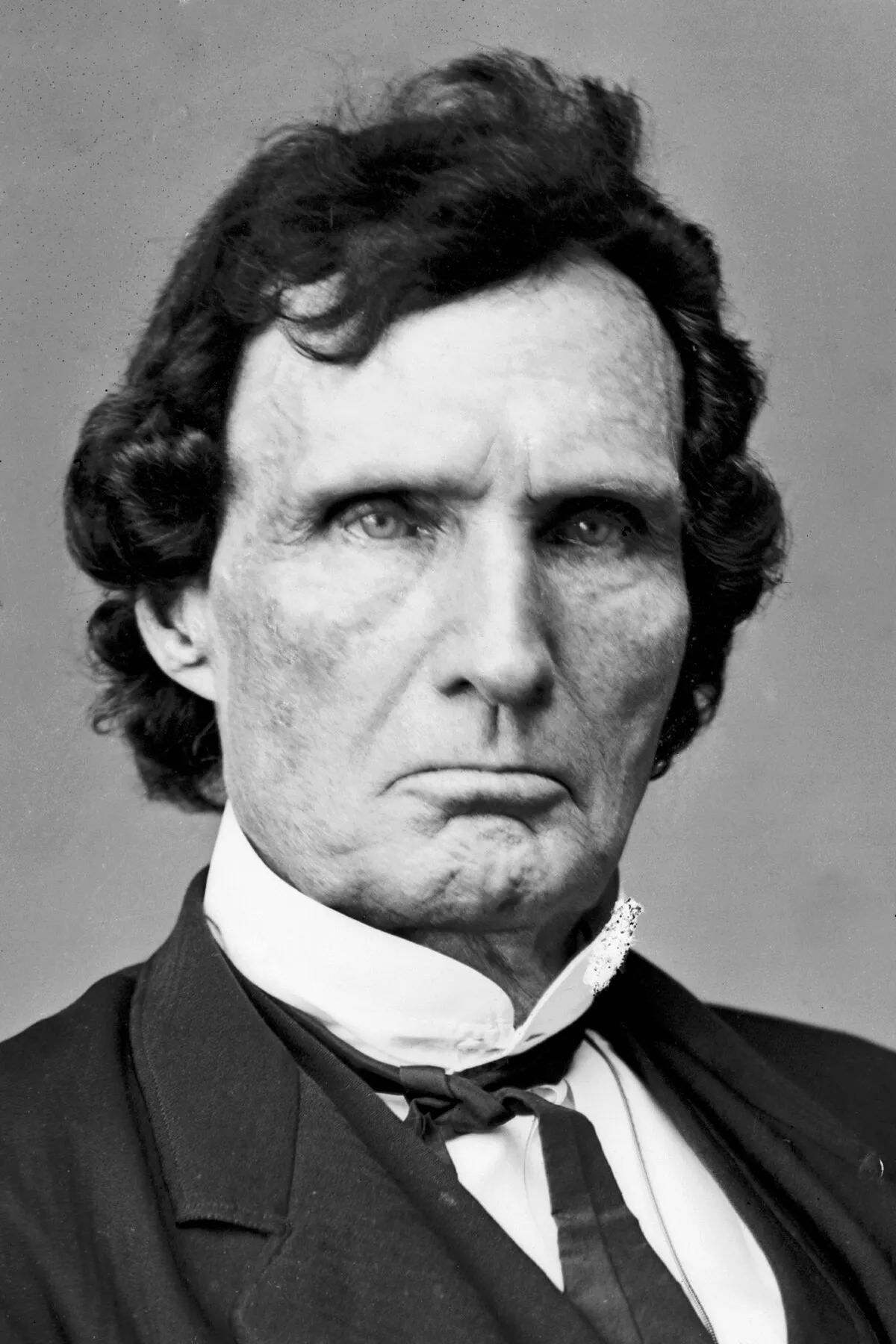

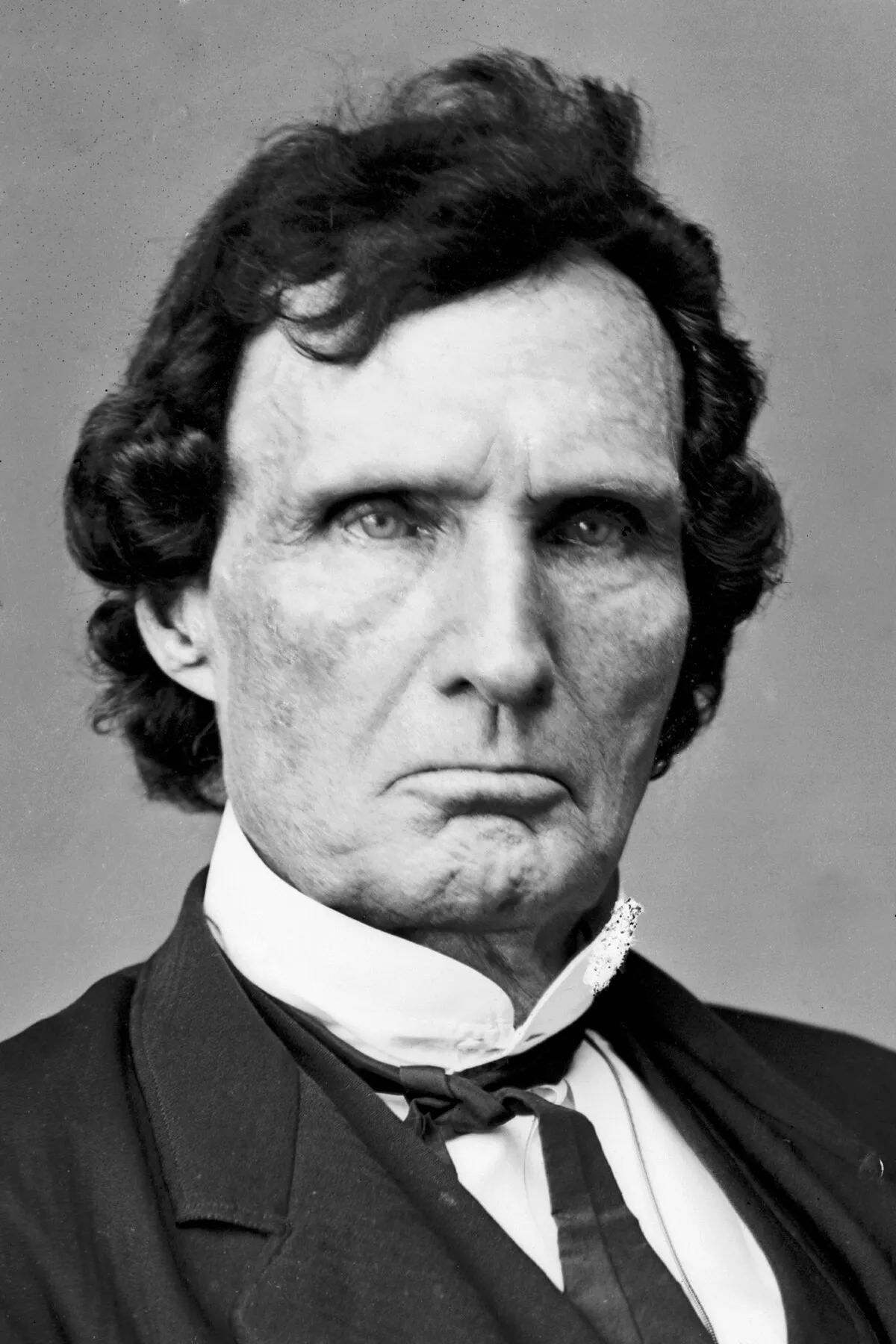

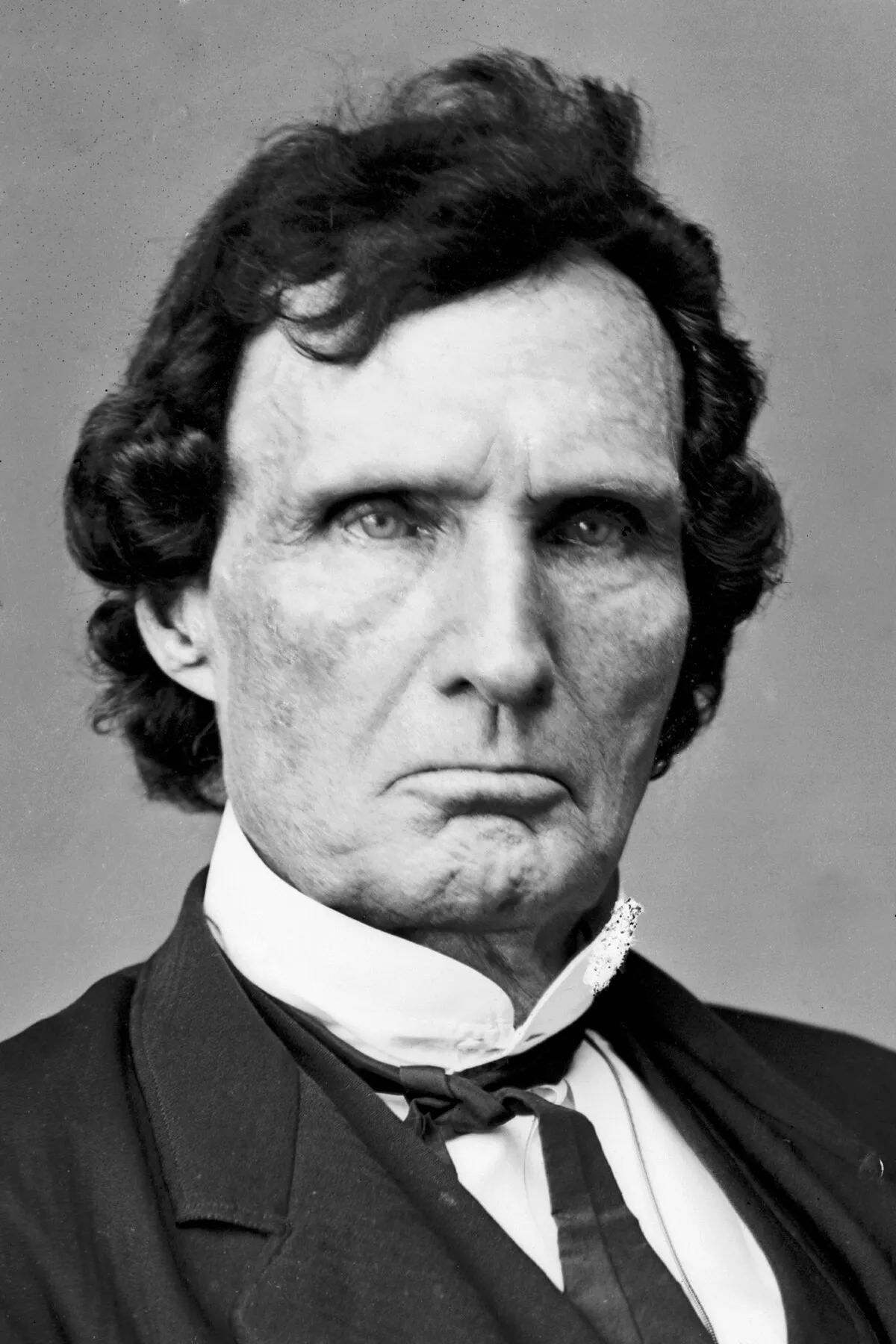

1. Thaddeus Stevens was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s.

1.

1. Thaddeus Stevens was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s.

Thaddeus Stevens was born in rural Vermont, in poverty, and with a club foot, which left him with a permanent limp.

Thaddeus Stevens was an active leader of the Anti-Masonic Party, as a fervent believer that Freemasonry in the United States was an evil conspiracy to secretly control the republican system of government.

Thaddeus Stevens was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, where he became a strong advocate of free public education.

Thaddeus Stevens argued that slavery should not survive the war; he was frustrated by the slowness of US President Abraham Lincoln to support his position.

Thaddeus Stevens guided the government's financial legislation through the House as Ways and Means chairman.

Thaddeus Stevens's plans went too far for the Moderate Republicans and were not enacted.

The difference in views caused an ongoing battle between Johnson and Congress, with Thaddeus Stevens leading the Radical Republicans.

Historiographical views of Thaddeus Stevens have dramatically shifted over the years, from the early 20th-century view of Thaddeus Stevens as reckless and motivated by hatred of the white South to the perspective of the neoabolitionists of the 1950s and afterward, who lauded him for his commitment to equality.

Thaddeus Stevens was the second of four children, all boys, and was named to honor the Polish general who served in the American Revolutionary War, Tadeusz "Thaddeus" Kosciuszko.

Thaddeus Stevens's parents were Baptists who had emigrated from Massachusetts around 1786.

Thaddeus Stevens was born with a club foot which, at the time, was seen by some as a judgment from God for secret parental sin.

Thaddeus Stevens's older brother was born with the same condition in both feet.

The boys' father, Joshua Thaddeus Stevens, was a farmer and cobbler who struggled to make a living in Vermont.

Sarah Thaddeus Stevens struggled to make a living from the farm even with the increasing aid of her sons.

Thaddeus Stevens was determined that her sons improve themselves, and in 1807 moved the family to the neighboring town of Peacham, Vermont, where she enrolled young Thaddeus in the Caledonia Grammar School.

Thaddeus Stevens suffered much from the taunts of his classmates for his disability.

Thaddeus Stevens then enrolled in the sophomore class at Dartmouth College.

Thaddeus Stevens graduated from Dartmouth in 1814 and spoke at the commencement ceremony.

Thaddeus Stevens began to read law in the office of John Mattocks.

In early 1815, correspondence with a friend, Samuel Merrill, a fellow Vermonter who had moved to York, Pennsylvania to become preceptor of the York Academy, led to an offer for Thaddeus Stevens to join the academy faculty.

Thaddeus Stevens moved to York to teach, and continued the study of law in the offices of David Cossett.

In Pennsylvania, Thaddeus Stevens taught school at the York Academy and continued his studies for the bar.

Thaddeus Stevens left Bel Air the next morning with a certificate allowing him, through reciprocity, to practice law anywhere.

Thaddeus Stevens's breakthrough, in mid-1817, was a case in which a farmer who had been jailed for debt later killed one of the constables who had arrested him.

Thaddeus Stevens was involved in the first ten cases to reach the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania from Adams County after he began his practice and won nine.

The rumors dogged him for years; when one newspaper opposed to Thaddeus Stevens printed a letter in 1831 naming him as the killer, he successfully sued for libel.

Thaddeus Stevens had been told by a fellow attorney James Buchanan that he could advance politically if he joined them.

Thaddeus Stevens took to Anti-Masonry with enthusiasm and remained loyal to it after most Pennsylvanians had dropped the cause.

Thaddeus Stevens quickly became prominent in the movement, attending the party's first two national conventions in 1830 and 1831.

In September 1833, Thaddeus Stevens was elected to a one-year term in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives as an Anti-Mason.

Thaddeus Stevens gained attention far beyond Pennsylvania for his oratory against Masonry and quickly became an expert in legislative maneuvers.

The witnesses invoked their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, and when Thaddeus Stevens verbally abused one of them, it created a backlash that caused his own party to end the investigation.

Nevertheless, Thaddeus Stevens remained an opponent of the order for the rest of his life.

Thaddeus Stevens opened his extensive private library to the public and gave up his presidency of the borough council, believing his service on the school board more important.

Thaddeus Stevens gave the school land upon which a building could be raised and served as a trustee for many years.

Thaddeus Stevens stated that opponents were seeking to separate the poor into a lower caste than themselves and accused the rich of greed and failure to empathize with the poor.

Thaddeus Stevens hoped that if the remaining Anti-Masons and the emerging Whig Party gained a majority, he could be elected to the United States Senate, whose members until 1913 were chosen by state legislatures.

Thaddeus Stevens won his seat in Adams County, and sought to have those Philadelphia Democrats excluded, which would create a Whig majority that could elect a Speaker and himself as a senator.

Thaddeus Stevens remained in the legislature for most years through 1842 but the episode cost him much of his political influence.

Thaddeus Stevens campaigned for the Whig candidate in the 1840 presidential election, former general William Henry Harrison.

In 1842, Thaddeus Stevens moved his home and practice to Lancaster.

Thaddeus Stevens knew Lancaster County was an Anti-Mason and Whig stronghold, which ensured that he retained a political base.

At the 1837 Pennsylvania constitutional convention, Thaddeus Stevens, who was a delegate, fought against the disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

Until the outbreak of the American Civil War, Thaddeus Stevens took the public position that he supported slavery's end and opposed its expansion.

Thaddeus Stevens supported slave-owning Whig candidates for president: Henry Clay in 1844 and Zachary Taylor in 1848.

Some delegates felt that because Thaddeus Stevens had been late to join the party, he should not receive the nomination; others disliked his stance on slavery.

Thaddeus Stevens spoke out against the Compromise of 1850, crafted by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, that gave victories to both North and South, but would allow for some of the territories of the United States recently gained from Mexico to become slave states.

Thaddeus Stevens was easily renominated and reelected in 1850, even though his stance caused him problems among pro-Compromise Whigs.

In 1851, Thaddeus Stevens was one of the defense lawyers in the trial of 38 African-Americans and three others in federal court in Philadelphia on treason charges.

Thaddeus Stevens left the Whig caucus in December 1851, when his colleagues would not join him in seeking the repeal of the offensive elements of the Compromise.

Out of office, Thaddeus Stevens concentrated on the practice of law in Lancaster, remaining one of the leading attorneys in the state.

Thaddeus Stevens stayed active in politics, and in 1854, to gain more votes for the anti-slavery movement, he joined the nativist Know Nothing Party.

The members were pledged not to speak of party deliberations, and Thaddeus Stevens was attacked for his membership in a group with similar secrecy rules as the Masons.

Thaddeus Stevens was a delegate to the 1856 Republican National Convention, where he supported Justice McLean, as he had in 1832.

However, the convention nominated John C Fremont, whom Stevens actively supported in the race against his fellow Lancastrian, the Democratic candidate James Buchanan.

Thaddeus Stevens returned to the practice of law, but in 1858, with the President and his party unpopular and the nation torn by such controversies as the Dred Scott decision, Thaddeus Stevens saw an opportunity to return to Congress.

Thaddeus Stevens took his seat in the 36th United States Congress in December 1859, only days after the hanging of John Brown, who had attacked the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry hoping to cause a slave insurrection.

Thaddeus Stevens opposed Brown's violent actions at the time, though later, he was more approving.

Thaddeus Stevens was active in the bitter flow of invective from both sides; at one point, Mississippi Congressman William Barksdale drew a knife on him, though no blood was spilled.

The President-elect's known opposition to the expansion of slavery caused immediate talk of secession in the southern states, a threat that Thaddeus Stevens had downplayed during the campaign.

Thaddeus Stevens was unyielding in opposing efforts to appease the southerners, such as the Crittenden Compromise, which would have enshrined slavery as beyond constitutional amendment.

Thaddeus Stevens stated, in a remark widely quoted both North and South, that rather than offer concessions because of Lincoln's election, he would see "this Government crumble into a thousand atoms," and that the forces of the United States would crush any rebellion.

Thaddeus Stevens believed that the Confederacy had placed itself beyond the protection of the US Constitution by making war, and that in a reconstituted United States, slavery should have no place.

In July 1861, Thaddeus Stevens secured the passage of an act to confiscate the property, including slaves, of certain rebels.

In November 1861, Thaddeus Stevens introduced a resolution to emancipate all slaves; it was defeated.

Thaddeus Stevens quickly adopted the Emancipation Proclamation for use in his successful re-election campaign.

Thaddeus Stevens, who had been there supervising operations, was hastened away by his workers against his will.

Early said that the North had done the same to southern figures and that Thaddeus Stevens was well known for his vindictiveness towards the South.

Thaddeus Stevens pushed Congress to pass a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery.

Lincoln campaigned aggressively for the amendment after his re-election in 1864, and Thaddeus Stevens described his December annual message to Congress as "the most important and best message that has been communicated to Congress for the last 60years".

Thaddeus Stevens closed the debate on the amendment on January 13,1865.

Thaddeus Stevens continued to push for a broad interpretation of it that included economic justice in addition to the formal end of slavery.

Thaddeus Stevens worked closely with Lincoln administration officials on legislation to finance the war.

Thaddeus Stevens played a major part in the passage of the Legal Tender Act of 1862 when for the first time, the United States issued currency backed only by its own credit, not by gold or silver.

In 1863, Thaddeus Stevens aided the passage of the National Banking Act, which required that banks limit their currency issues to the number of federal bonds that they were required to hold.

Thaddeus Stevens was unrepentant even as the value of paper currency recovered in late 1864 amid the expectation of Union victory, proposing legislation to make paying a premium in greenbacks for an amount in gold coin a criminal offense.

Thaddeus Stevens reluctantly voted for Lincoln at the convention of the National Union Party, a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats.

Thaddeus Stevens would have preferred to vote for the sitting vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, as Lincoln's running mate in 1864.

When in January 1865 Congress learned that Lincoln had attempted peace talks with Confederate leaders, an outraged Thaddeus Stevens declared that if the American electorate could vote again, they would elect General Benjamin Butler instead of Lincoln.

Thaddeus Stevens did not attend the ceremonies when Lincoln's funeral train stopped in Lancaster; he was said to be ill.

When his communications were ignored, Thaddeus Stevens began to discuss with other radicals how to prevail over Johnson when the two houses convened.

Congress has the constitutional power to judge whether those seeking to be its members are properly elected; Thaddeus Stevens urged that no senators or representatives from the South be seated.

Thaddeus Stevens argued that the states should not be readmitted as thereafter Congress would lack the power to force race reform.

Thaddeus Stevens proposed that the government confiscate the estates of the largest 70,000 landholders there, those who owned more than 200 acres.

Thaddeus Stevens warned that under the President's plan, the southern states would send rebels to Congress who would join with northern Democrats and Johnson to govern the nation and perhaps undo emancipation.

When Congress convened in early December 1865, Thaddeus Stevens made arrangements with the Clerk of the House that when the roll was called, the names of the Southern electees be omitted.

Thaddeus Stevens focused on legislation that would secure the freedom promised by the newly ratified Thirteenth Amendment.

Thaddeus Stevens proposed and then co-chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction with Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden.

Thaddeus Stevens declared: that "our loyal brethren at the South, whether they be black or white," required urgent protection "from the barbarians who are now daily murdering them".

Thaddeus Stevens had begun drafting versions in December 1865, before the Committee had even formed.

Thaddeus Stevens believed that the Declaration of Independence and Organic Acts already bound the federal government to these principles, but that an amendment was necessary to allow enforcement against discrimination at the state level.

The resolution providing for what would become the Fourteenth Amendment was watered down in Congress; during the closing debate, Thaddeus Stevens said these changes had shattered his lifelong dream in equality for all Americans.

When Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull introduced legislation to reauthorize and expand the Freedmen's Bureau, Thaddeus Stevens called the bill a "robbery" because it did not include sufficient provisions for land reform or protect the property of refugees given them by the military occupation of the South.

Thaddeus Stevens criticized the passage of the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, arguing that the low-quality land it made available would not drive real economic growth for black families.

Thaddeus Stevens attacked Stevens and other radicals during this tour.

Thaddeus Stevens campaigned for firm measures against the South, his hand strengthened by violence in Memphis and New Orleans, where African-Americans and white Unionists had been attacked by mobs, including the police.

Thaddeus Stevens was returned to Congress by his constituents; Republicans would have a two-thirds majority in both houses in the next Congress.

In January 1867, Thaddeus Stevens introduced legislation to divide the South into five districts, each commanded by an army general empowered to override civil authorities.

Thaddeus Stevens introduced a Tenure of Office Act, restricting Johnson from firing officials who had received Senate confirmation without getting that body's consent.

Thaddeus Stevens steered a bill to enfranchise African-Americans in the District of Columbia through the House.

Congress was downsizing the Army for peacetime; Thaddeus Stevens offered an amendment, which became part of the bill as enacted, to have two regiments of African-American cavalry.

Thaddeus Stevens added a stipulation into the [Transcontinental] Pacific Railroad Act requiring the applicable railroads to buy iron "of American manufacture" of the top price qualities.

Thaddeus Stevens advocated a bill to give government workers raises; it did not pass.

Thaddeus Stevens firmly supported impeachment, but others were less enthusiastic once the Senate elected Ohio's Benjamin Wade as its president pro tempore, next in line to the presidency in the absence of a vice president.

Thaddeus Stevens was chairman of the House Select Committee on Reconstruction, which was tasked by the House on January 27,1868, with running a second impeachment inquiry.

On February 13,1868, Thaddeus Stevens presented to the committee a report accusing Johnson of actions that intended to violate the Tenure of Office Act.

Thaddeus Stevens led the delegation of House members sent the following day to inform the Senate of the impeachment, though he had to be carried to its doors by his bearers.

Nevertheless, dissatisfied with the committee's proposed articles, Thaddeus Stevens suggested another that would become ArticleXI.

Thaddeus Stevens was one of the House impeachment managers elected by the House to present its case in the impeachment trial.

Increasingly ill, Stevens took little part in the impeachment trial, at which the leading House manager was Massachusetts Representative Benjamin F Butler.

Thaddeus Stevens nourished himself on the Senate floor with raw eggs and terrapin, port and brandy.

Thaddeus Stevens focused on ArticleXI, taking the position that Johnson could be removed for political crimes; he need not have committed an offense against the law.

Thaddeus Stevens, though, was never certain of the result as Chief Justice Chase made rulings that favored the defense, and he had no great confidence Republicans would stick together.

Thaddeus Stevens offered a bill to divide Texas into several parts to gain additional Republican senators to vote out Johnson.

Thaddeus Stevens was in pain from his stomach ailments, from swollen feet, and from dropsy.

Thaddeus Stevens still received some visitors, though, and correctly predicted to his friend and former student Simon Stevens that Grant would win the election.

Thaddeus Stevens sucked on ice to try to soothe the pain; his last words were a request for more of it.

Thaddeus Stevens died on the night of August 11,1868, as the old day departed.

Thaddeus Stevens's body was conveyed from his house to the Capitol by white and black pallbearers together.

Thousands of mourners, of both races, filed past his casket as he lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda; Thaddeus Stevens was the third man, after Clay and Lincoln, to receive that honor.

Thaddeus Stevens was laid to rest in Shreiner's Cemetery ; it allowed the burial of people of all races, although, at the time of Thaddeus Stevens's interment, only one African-American was buried there.

When Congress convened in December 1868, there were several speeches in tribute to Thaddeus Stevens; they were afterward collected in book form.

Thaddeus Stevens never married, though there were rumors about his twenty-year relationship with his widowed housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith.

Thaddeus Stevens was a light-skinned African American; her husband Jacob and at least one of her sons were much darker than she was.

Thaddeus Stevens insisted that his nieces and nephews refer to her as "Mrs Smith", despite deference towards an African-American servant being almost unheard of at that time.

Thaddeus Stevens expresses his bitterness about his own inability to gain election by the legislature to the Senate, or to secure a Cabinet position.

Thaddeus Stevens was baptized a Catholic by one of the nuns on his deathbed.

Early biographical works on Thaddeus Stevens were composed by men who knew him and reflected their viewpoints.

Current argued that Thaddeus Stevens was motivated in his Reconstruction policies by frustrated ambitions and a desire to use his political position to promote industrial capitalism and advance the Republican Party.

Controversial in its conclusions for being a psychobiography, it found that Thaddeus Stevens was a "consummate underdog who identified with the oppressed" and whose intelligence won him success, while his consciousness of his clubfoot stunted his social development.

In 1989, Allan Bogue found that as chairman of Ways and Means, Thaddeus Stevens was "less than complete master" of his committee.

When Lincoln appointed rival Pennsylvania Republican leader Simon Cameron as Secretary of War, Thaddeus Stevens expressed disgust at Cameron's reputed corruption.

Steven Spielberg's 2012 film Lincoln, in which Thaddeus Stevens was portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones, brought new public interest in Thaddeus Stevens.

Historian Matthew Pinsker notes that Thaddeus Stevens is referred to only four times in Doris Kearns Goodwin's 2005 book Team of Rivals, on which screenwriter Tony Kushner based the film's screenplay; other radicals were folded into the character.

Thaddeus Stevens is depicted as unable to moderate his views for the sake of gaining passage of the amendment until after he is urged to do so by the ever-compromising Lincoln.