1.

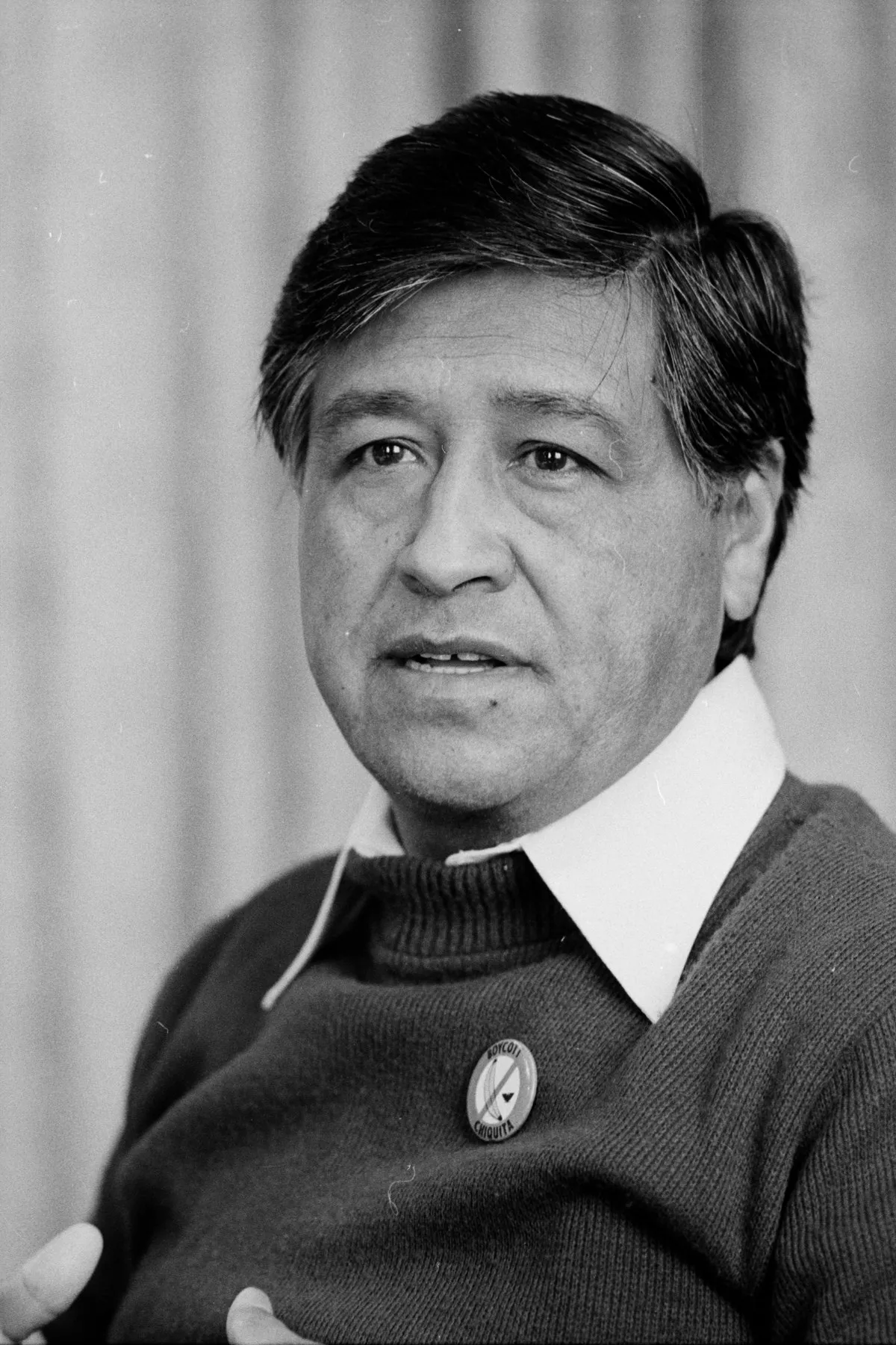

1. Cesar Chavez imbued his campaigns with Roman Catholic symbolism, including public processions, Masses, and fasts.

1.

1. Cesar Chavez imbued his campaigns with Roman Catholic symbolism, including public processions, Masses, and fasts.

Cesar Chavez received much support from labor and leftist groups but was monitored by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Cesar Chavez's increased isolation and emphasis on unrelenting campaigning alienated many California farmworkers who had previously supported him, and by 1973 the UFW had lost most of the contracts and membership it won during the late 1960s.

Cesar Chavez became an icon for organized labor and leftist groups in the US Posthumously, he became a "folk saint" among Mexican Americans.

Cesar Chavez's birthday is a federal commemorative holiday in several US states, while many places are named after him, and in 1994 he posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Cesario Estrada Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona on March 31,1927.

Cesar Chavez was named after his paternal grandfather, Cesario Chavez, a Mexican who had crossed into Texas in 1898.

Librado and Juana's first child, Rita, was born in August 1925, with their first son, Cesar Chavez, following nearly two years later.

Cesar Chavez was raised in what his biographer Miriam Pawel called "a typical extended Mexican family"; she noted that they were "not well-off, but they were comfortable, well-clothed, and never hungry".

The Cesar Chavez family joined the growing number of American migrants who were moving to California amid the Great Depression.

Cesar Chavez graduated from junior high in June 1942, after which he left formal education and became a full-time farm laborer.

In 1944, Cesar Chavez enlisted in the US Navy, and was sent to Naval Training Center San Diego.

Cesar Chavez was then stationed to San Francisco, where he decided to leave the Navy, receiving an honorable discharge in 1946.

In 1947, Cesar Chavez joined the National Farm Labor Union, which, until its 1947 affiliation with the American Federation of Labor, was the Southern Tenant Farmers Union.

Cesar Chavez entered a relationship with Helen Fabela, who soon became pregnant.

The latter had been born shortly after they had relocated to Crescent City, where Cesar Chavez was employed in the lumber industry.

Cesar Chavez helped Ross establish a chapter of his Community Service Organization in San Jose, and joined him in voter registration drives.

Cesar Chavez was voted vice president of the CSO chapter.

Cesar Chavez helped McDonnell construct the first purpose-built church in Sal Si Puedes, the Our Lady of Guadalupe church, which opened in December 1953.

In turn, McDonnell lent Cesar Chavez books, encouraging the latter to develop a love of reading.

In late 1953, Cesar Chavez was laid off by the General Box Company.

Many of the CSO chapters fell apart after Ross or Cesar Chavez ceased running them, and to prevent this Saul Alinsky advised them to unite the chapters, of which there were over twenty, into a self-sustaining national organization.

In late 1955, Cesar Chavez returned to San Jose to rebuild the CSO chapter there so that it could sustain an employed full-time organizer.

Cesar Chavez's repeated moving meant that his family were regularly uprooted; he saw little of his wife and children, and was absent for the birth of his sixth child.

Cesar Chavez grew increasingly disillusioned with the CSO, believing that middle-class members were becoming increasingly dominant and were pushing its priorities and allocation of funds in directions he disapproved of; he for instance opposed the decision to hold the organization's 1957 convention in Fresco's Hacienda Hotel, arguing that its prices were prohibitive for poorer members.

Amid the wider context of the Cold War and McCarthyite suspicions that leftist activism was a front for Marxist-Leninist groups, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began monitoring Cesar Chavez and opened a file on him.

At Alinsky's instigation, the United Packinghouse Workers of America paid $20,000 to the CSO for the latter to open a branch in Oxnard; Cesar Chavez became its organizer, working with the largely Mexican farm laborers.

Cesar Chavez repeatedly heard concerns from local Mexican-American laborers that they were being routinely passed over or fired so that employers could hire cheaper Mexican guest workers, or braceros, in violation of federal law.

In 1959, Cesar Chavez moved to Los Angeles to become the CSO's national director.

Cesar Chavez found the CSO's financial situation was bad, with even his own salary in jeopardy.

Cesar Chavez laid off several organizers to keep the organization afloat.

Cesar Chavez tried to organize a life insurance scheme among CSO members to raise funds, but this project failed to materialize.

Cesar Chavez was intent on forming a labor union for farm workers but, to conceal this aim, told people that he was simply conducting a census of farm workers to determine their needs.

Cesar Chavez began devising the National Farm Workers Association, referring to it as a "movement" rather than a trade union.

Cesar Chavez was aided in this project both by his wife and by Dolores Huerta; according to Pawel, Huerta became his "indispensable, lifelong ally".

Cesar Chavez spent his days traveling around the San Joaquin Valley, meeting with workers and encouraging them to join his association.

At the organization's constitutional convention held in Fresno in January 1963, Cesar Chavez was elected president, with Huerta, Julio Hernandez, and Gilbert Padilla its vice presidents.

Cesar Chavez wanted to control the NFWA's direction and to that end ensured that the role of the group's officers was largely ceremonial, with control of the group being primarily in the hands of the staff, headed by himself.

At the NFWA's second convention, held in Delano in 1963, Cesar Chavez was retained as its general director while the role of the presidency was scrapped.

The strike covered an area of over 400 square miles ; Cesar Chavez divided the picketers among four quadrants, each with a mobile crew led by a captain.

Cesar Chavez insisted that the strikers must never respond with violence.

Cesar Chavez met with representatives of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which became an important ally of the strikers.

The third, which took place in Delano, was attended by Senator Robert F Kennedy, who toured a labor camp with Chavez and addressed a mass meeting.

Cesar Chavez then declared an end to the Schenley boycott; instead, the movement would switch the boycott to the DiGiorgio Corporation, a major Delano land owner.

Cesar Chavez then appealed to Pat Brown, the Governor of California, to intervene.

Not all of Cesar Chavez's staff agreed with the merger; many of its more left-wing members mistrusted the growing links with organized labor, particularly due to the AFL-CIO's anti-communist views.

Cesar Chavez brought new people, such as LeRoy Chatfield, Marshall Ganz, and the lawyer Jerry Cohen, into his inner circle.

In June 1967, Cesar Chavez launched his first purge of the union to remove those he deemed disruptive or disloyal to his leadership.

Cesar Chavez's cover story was that he wanted to eject members of the Communist Party USA and related far-left groups, although the FBI's report at the time found no evidence of communist infiltration of the union.

Cesar Chavez was concerned that the Teatro had become a rival to his prominent standing in the movement and was questioning his actions.

Cesar Chavez asked the Teatro to disband, at which it split from the union and went on a tour of the US.

Cesar Chavez hoped for it to be a "spiritual" center where union members would relax; he designed it to have a swimming pool, a chapel, a market, and a gas station, as well as gardens with outdoor sculptures.

Cesar Chavez wanted the main building to be decorated inside with Gandhi quotations in English and Spanish.

Meanwhile, Cesar Chavez was increasingly concerned that his supporters might turn to violence.

In February 1968, Cesar Chavez began a fast; he publicly stated that in doing so he was reaffirming his commitment to peaceful protest and presented it as a form of penance.

Cesar Chavez stated that he would remain at Forty Acres for the duration of his fast, which at this point had only a gas station there.

Many members of the union were critical of what they saw as a stunt; Itliong was annoyed that Cesar Chavez had not consulted the union's board before making his declaration.

The union introduced a motion urging Cesar Chavez to cancel his plan, although this failed.

Cesar Chavez invited Robert Kennedy to be the guest of honor at this event.

Cesar Chavez asked Chavez to run as a delegate in the California primary.

Cesar Chavez's activism was a contributing factor to Kennedy's victory in that state.

Cesar Chavez then attended Kennedy's New York funeral as a pallbearer.

Kennedy's assassination came two months after that of Martin Luther King, generating growing concerns among the union that Cesar Chavez would be targeted by those who opposed him.

Cesar Chavez followed this with a recuperation stay at St Anthony's Seminary in Santa Barbara.

Cesar Chavez returned home, but finding it too crowded moved in to Forty Acres.

Cesar Chavez used his image of physical suffering as a tactic in his cause, although some of his inner circle thought his pain to be at least partially psychosomatic.

In July 1969, Cesar Chavez's portrait appeared on the front of Time magazine.

In March 1969, the doctor Janet Travell visited Cesar Chavez and determined that fused vertebrae were the source of his back pain.

Cesar Chavez prescribed various exercises and other treatments which he found eased his pain.

Cesar Chavez demanded that the CRLA make its staff available for union work and that it would allow the union's attorneys to decide which cases the CRLA would pursue.

Cesar Chavez insisted that their negotiations cover issues at the Delano High School, where several pupils, including his own daughter Eloise, had been suspended or otherwise disciplined for protesting in support of the boycott.

Cesar Chavez was angry at this, traveling to Salinas to talk with the lettuce cutters, many of whom were dissatisfied with the way that the Teamsters represented them.

Cesar Chavez decided that the strike should initially target the valley's largest lettuce grower, Interharvest, which was owned by the United Fruit Company.

The Salinas lettuce growers secured a temporary restraining order preventing a strike, at which Cesar Chavez initiated another protest fast.

Cesar Chavez selected the Bud Antle company as the first target of the boycott campaign.

Cesar Chavez took part in a rally which included a Roman Catholic Mass; it was opposed by a group of local counter-protesters who opposed the concentration of leftist activism in their community.

Cesar Chavez wanted a more remote base for his movement than Forty Acres, especially one where he could experiment with his ideas about communal living.

Cesar Chavez named this new base Nuestra Senora Reina de la Paz, although it became commonly known just as "La Paz".

La Paz became the union's new headquarters, something that various backers and funders were critical of due to its remote location; Cesar Chavez said that this was necessary for his security, particularly following allegations of a plot against his life.

Farmworkers rallied outside Williams' office while Cesar Chavez embarked on a fast in the Santa Rita Center, a hall used by a local Chicano group.

Cesar Chavez then broke the fast at a memorial Mass on the anniversary of Robert Kennedy's death, where he was joined by the folk singer Joan Baez.

Cesar Chavez increasingly pushed for the UFW to become a national organization, with a token presence being established in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Texas, and Florida.

Cesar Chavez pushed for the California Migrant Ministry, which supported the UFW, to transform into a National Farm Worker Ministry, insisting that the UFW should have the power to veto decisions made by the NFWM.

At the AFL-CIO's request, Cesar Chavez had suspended the Salinas lettuce boycott, but prepared to relaunch it eight months later as the growers had only conceded to one of their demands.

In early 1972, Richard visited Cesar Chavez and confronted him about the problems in Delano, telling him that the union was losing support among farmworkers and that they were in danger of losing the contracts when they came up for renewal.

In Richard's opinion, Cesar Chavez was losing touch with the union's membership.

Cesar Chavez responded to these criticisms by reassigning his brother away from Delano.

Cesar Chavez tasked LeRoy Chatfield with running the campaign against it; at the ballot, Proposition 22 lost by 58 percent to 42 percent.

At this, Cesar Chavez called a strike in the Coachella Valley.

Cesar Chavez agreed; although he did not want such a law and he thought that Governor Reagan would never agree to it anyway.

Cesar Chavez then called off the Delano strike, stating that he would do so until the federal government guaranteed the safety of UFW protesters; the government believed that this was a cover to conceal the financial problems that the strike was causing the UFW.

The new executive committee, which included Huerta and Richard Cesar Chavez, was racially mixed, although some members expressed dissatisfaction that it did not contain more Mexican Americans.

Cesar Chavez flew to Europe to urge the unions there to block the imported goods that the UFW were sending there.

Cesar Chavez traveled through London, Oslo, Stockholm, Geneva, Hamburg, Copenhagen, Brussels, and Paris, although he found that the unions were cautious about joining his campaign.

Cesar Chavez increasingly blamed the failure of the UFW strike on illegal immigrants who were brought in as strikebreakers.

Cesar Chavez made the unsubstantiated claim that the CIA was involved in part of a conspiracy to bring illegal migrants into the country so that they could undermine his union.

Cesar Chavez launched the "Illegals Campaign" to identify illegal migrants so that they could be deported, appointing Liza Hirsch to oversee the campaign.

Cesar Chavez believed that any strike undertaken by agricultural workers could be undermined by "wetbacks" and "illegal immigrants".

Cesar Chavez repeatedly said that his boycott was a much better organizing tool because the law would always be corrupted by the powerful economic interests that control politics.

Cesar Chavez dismissed the reports of violence as the smears of paid provocateurs, a claim which many of his supporters accepted.

Cesar Chavez protected Manuel, while the executive board kept silent on his activities, regarding him as useful.

The Chicano activist Bert Corona staged a protest against the UFW wet line, at which Cesar Chavez directed Jerry Cohen to launch an investigation into the funding of Corona's group.

In 1974, Cesar Chavez proposed the idea of a Poor People's Union with which he could reach out to poor white communities in the San Joaquin Valley who were largely hostile to the UFW.

Cesar Chavez met with Brown and together they developed a strategy: Brown would introduce a bill to improve farmworkers' rights, at which the UFW would support a more radical alternative.

Brown appointed a five-person board to lead the ALRB which was sympathetic to Cesar Chavez; it included the former UFW official LeRoy Chatfield.

The Teamster victories in the Delano vineyards angered Cesar Chavez, who insisted that there had not been free elections there.

Cesar Chavez criticised the ALRB and launched a targeted campaign against Walter Kintz, the ALRB's general counsel, demanding his resignation.

Cesar Chavez put pressure on Governor Brown to remove Kintz.

Meanwhile, to develop the UFW's administration, Cesar Chavez hired the management consultant Crosby Milne, whose ideas led to a restructuring of the union.

In July 1976, Cesar Chavez traveled to New York to attend the Democratic Party's National Congress, at which he gave a speech nominating Brown as the party's presidential candidate.

Cesar Chavez thought that Proposition 14 had little chance of being passed by the electorate and was concerned that devoting its resources to the campaign would be financially costly for the UFW.

Cesar Chavez blamed the defeat on the UFW's national boycott director, Nick Jones, who had been the only staff member to publicly voice disquiet over the Proposition 14 campaign.

Under pressure, in November 1976, Jones resigned; in a letter to the executive board he stated that he was "deeply concerned" about the direction in which Cesar Chavez was taking the union.

Cesar Chavez fired Joe Smith, the editor of El Macriado, after accusing him of deliberately undermining the newspaper.

Cesar Chavez then ordered Ross and Ganz to interrogate everyone who worked on the campaign, ostensibly to decide on new assignments but to route out alleged malcontents, agitators, and spies.

Many of those involved in running the UFW's boycott expressed concerns about a McCarthyite-style atmosphere developing within the union, and Cesar Chavez's purge attracted press attention.

Cesar Chavez became convinced that there was a far-left conspiracy, whose members he called the "assholes" or "them", who were trying to undermine the UFW.

At a La Paz meeting in April 1977, later called "the Monday Night Massacre", Cesar Chavez called together a range of individuals whom he denounced as malcontents or spies.

Cesar Chavez later accused Philip Vera Cruz, the oldest member of the executive board, of being part of the conspiracy, and forced him out.

Cesar Chavez reversed many of the changes he had implemented under Milne's guidance, with executive board members being reassigned to cover geographic areas rather than having union-wide responsibilities.

Milne, who had been living at La Paz, soon left, with Cesar Chavez later alleging he had been part of a conspiracy against the union.

Cesar Chavez told the executive committee that radical change was necessary in the UFW; he stated that they could be either a union or a movement, but not both.

Cesar Chavez instead urged them to become a movement, which he argued meant establishing communal settlements for members, drawing on a Californian religious organization, Synanon, as an exemplar.

Cesar Chavez had become increasingly interested in Synanon, a drug-treatment organization that had declared itself a religion in 1975 and which operated out of a compound east of Fresno.

Cesar Chavez admired Synanon's leader Charles Dederich, and the way that the latter controlled his planned community.

In Cesar Chavez's opinion, Dederich was "a genius in terms of people".

In February 1977, Cesar Chavez took the UFW's executive board on a visit to the Synanon compound.

Cesar Chavez received tacit agreement from the executive board, although some of its members privately opposed the measure.

Cesar Chavez remained enthusiastic about the Game, calling it "a good tool to fine-tune the union".

Many of those close to Cesar Chavez, including his wife and Richard Cesar Chavez, refused to take part.

Synanon provided the UFW with $100,000 worth of cars and materials; building links with Cesar Chavez's movement burnished Dederich's reputation with rich liberals who were among Synanon's core constituency.

Cesar Chavez created a curriculum for them to follow, which included the Game.

Whereas Cesar Chavez had previously refused to accept government money, he now applied for over $500,000 in grants for a school and other projects.

Formal celebrations and group rituals became an important part of life at La Paz, while Cesar Chavez declared that on Saturday mornings all residents of La Paz should work in the vegetable and flower gardens to improve sociability.

Cesar Chavez then spoke to a reporter from The Washington Post where he spoke positively about Marcos' introduction of martial law.

Cesar Chavez then organized an event on Delano for five senior Filipino government officially to speak to an assembled audience.

Synanon launched a boycott of Time in response, with Cesar Chavez urging the UFW to support it, stating that they should assist their friends and help protect religious freedom.

The UFW stopped using the Game in response to these developments; Cesar Chavez's calls for it to resume were rejected by other senior members.

Cesar Chavez framed the issue along the lines of whether the UFW should start paying wages to everyone or instead continue to rely on volunteers.

In June 1978, Cesar Chavez joined a picket in Yuma as part of his cousin Manuel's Arizona melon strike.

Cesar Chavez organized a new strike over wages, hoping that salary increases would stem the UFW's losses; the union made its wage demands in January 1979, days after its contracts had expired.

Cesar Chavez urged the strikers not to resort to violence and with Contreras' father led a three-mile candlelit funerary procession, attended by 7000 people.

Cesar Chavez continued arguing for a boycott, suggesting that the union could use alcoholics from the cities to run the boycott campaign, an idea most of the executive board rejected.

Cesar Chavez brought these paid representatives to La Paz for a five-day training session in May 1980.

Ganz, who was becoming increasingly distant from Cesar Chavez, helped tutor them.

Cesar Chavez called all staff to a meeting at La Paz in May 1981, where he again insisted that the UFW was being infiltrated by spies seeking to undermine it and overthrow him.

Cesar Chavez arranged for more of his loyalists to be put on the executive board, which now had no farmworkers sitting on it.

Cesar Chavez's supporters responded with leaflets claiming that the paid representatives were puppets of "the two Jews", Ganz and Cohen, who were trying to undermine the union.

Cesar Chavez responded with a counter-suit, suing them for libel and slander.

Cesar Chavez acknowledged to a reporter that in doing so, he was trying to intimidate the protester's lawyer, something which brought negative publicity for the UFW.

In court, Cesar Chavez denied that the paid representatives were ever elected, alleging that they were appointed by him personally, but produced no evidence to support this claim.

The US District Court Judge William Ingram rejected Cesar Chavez's argument, ruling that the sacking of the paid representatives had been unlawful.

Cesar Chavez was involving himself in a broader range of leftist events.

Cesar Chavez co-chaired Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda's fund-raising dinner for their Campaign for Economic Democracy.

In November 1984, Cesar Chavez gave a speech to the Commonwealth Club of California.

Cesar Chavez launched a boycott of Lucky, a California supermarket chain.

Cesar Chavez's strategy was to convince the supermarket that the UFW could damage its patronage among Latinos.

Cesar Chavez had observed that the Christian Right was beginning to use new computer technologies to reach potential supporters and decided that the UFW should do the same.

Cesar Chavez linked this approach in with the ongoing boycott of Bruce Church, arguing that if consumers boycotted the company's products, the growers would stop using pesticides.

Cesar Chavez was replaced by the Republican George Deukmejian, who had the backing of the state's growers; under Deukmejian, the ALRB's influence eroded.

The fast was followed by further purges at La Paz as Cesar Chavez accused more people of being saboteurs.

In October 1990, Coachella became the first district to name a school after Cesar Chavez; he attended the dedication ceremony.

Cesar Chavez set himself up as a housing developer, working in partnership with the Fresno businessman Celestino Aguilar.

Cesar Chavez had sued the union, claiming it libeled them and had illegally threatened supermarkets to stop them selling Red Coach lettuce.

Cesar Chavez was called to testify in front of a Yuma court in 1993.

Cesar Chavez's body was flown to Bakersfield aboard a chartered plane.

Cesar Chavez had already stipulated that he wanted his brother Richard to build his coffin, and that his funeral should take place at Forty Acres.

Cesar Chavez was then buried in a private ceremony at La Paz.

When Cesar Chavez returned home from his service in the military in 1948, he married his high school sweetheart, Helen Fabela.

Cesar Chavez's children resented the union and displayed little interest in it, although most ended up working for it.

Cesar Chavez expressed traditional views on gender roles and was little influenced by the second wave feminism that was contemporary with his activism.

Huerta stated that she was Cesar Chavez's "whipping girl" when he was under pressure.

Cesar Chavez never had close friendships outside of his family, believing that friendships distracted from his political activism.

Cesar Chavez was quiet, and Bruns described him as being "outwardly shy and unimposing".

Cesar Chavez could be self-conscious about his lack of formal education and was uncomfortable interacting with affluent people.

Cesar Chavez was not a great orator; according to Pawel, "his power lay not in words, but in actions".

Cesar Chavez noted that he was "not an articulate speaker", and similarly, Bruns observed that he "had no special talent as a public speaker".

Cesar Chavez was soft-spoken, and according to Pawel had an "informal, conversational style", and was "good at reading people".

Cesar Chavez was capable of responding quickly and decisively to events.

Bruns described Cesar Chavez as combining a "remarkable tenacity with a sense of serenity".

Cesar Chavez described his own life's work as a crusade against injustice, and displayed a commitment to self-sacrifice.

Pawel thought that "Cesar Chavez thrived on the power to help people and the way that made him feel".

Pawel noted that Cesar Chavez was "openly ruthless" in his "drive to be the one and only farm labor leader".

Cesar Chavez was stubborn and would rarely back down once he had taken a stance.

Cesar Chavez was a Catholic whose faith strongly influenced both his social activism and his personal outlook.

Cesar Chavez rarely missed Mass and liked to open all of his meetings with either a Mass or a prayer.

Cesar Chavez credited this diet with easing his chronic back pain.

Cesar Chavez had a love of the music of Duke Ellington and big band music; he enjoyed dancing.

Cesar Chavez was an amateur photographer, and a keen gardener, making his own compost and growing vegetables.

Cesar Chavez disliked telephone conversations, suspecting that his phone line was bugged.

Cesar Chavez tended to see problems faced by his movement not as evidence of innocent mistakes but as deliberate sabotage.

Cesar Chavez was self-educated, with Pawel noting that he was "disinclined to analyze information".

Once Cesar Chavez accepted an idea, he could dedicate himself to it wholeheartedly.

Cesar Chavez described his movement as promoting "a Christian radical philosophy".

Cesar Chavez saw his fight for farmworkers' rights as a symbol for the broader cultural and ethnic struggle for Mexican Americans in the United States.

Cesar Chavez utilized a range of tactics drawing on Roman Catholic religion, including vigils, public prayers, a shrine on the back of his station wagon, and references to dead farmworkers as "martyrs".

Cesar Chavez called on his fellow Roman Catholics to be more consistent in standing up for the religion's values.

Cesar Chavez abhorred poverty, regarding it as dehumanizing, and wanted to ensure a better standard of living for the poor.

Cesar Chavez was frustrated that most farmworkers appeared more interested in money and did not appreciate the values that he espoused.

Cesar Chavez was concerned that, as he had seen with the CSO, individuals moving out of poverty often adopted middle-class values; he viewed the middle classes with contempt.

Cesar Chavez recognized that union activity was not a long-term solution to poverty across society and suggested that forming co-operatives therefore might be the best solution.

Cesar Chavez embraced ideals about communal living, and saw the La Paz commune he established in California as a model for others to follow.

Cesar Chavez repeatedly referred to himself as the leader of the "non-violent Viet Cong", a reference to the Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist militia that the US was combating in the Vietnam War.

Cesar Chavez was interested not only in Gandhi's ideas on non-violence but in the Indian's voluntary embrace of poverty, his use of fasting, and his ideas about community.

Cesar Chavez saw it not as a tactic to pressure his opponents, but rather to motivate his supporters, keeping them focused on the cause and on avoiding violence.

Cesar Chavez saw it as a sign of solidarity with the suffering of the people.

Apart from Catholic social teaching, the movement of Cesar Chavez was based on liberation theology, emphasizing liberation of the poor and self-sacrifice in the pursuit of justice.

Cesar Chavez saw parallels in the way that African Americans were treated in the United States to the way that he and his fellow Mexican Americans were treated.

Cesar Chavez absorbed many of the tactics that African American civil rights activists had employed throughout the 1960s, applying them to his own movement.

Cesar Chavez recognized the impact that his farm-worker campaigns had had on the Chicano Movement during the early 1970s, although he kept his distance from the latter movement and many of its leaders.

Cesar Chavez condemned the violence that some figures in the Chicano Movement espoused.

Cesar Chavez placed the success of the movement above all else; Pawel described him as "the ultimate pragmatist".

Cesar Chavez felt that he had to be both the leader and the organizer-in-chief of his movement because only he had the necessary commitment to the cause.

Cesar Chavez was interested in power and how to use it; although his role model in this was Gandhi, he studied the ideas about power by Niccolo Machiavelli, Adolf Hitler, and Mao Zedong, drawing ideas from each.

Cesar Chavez repeatedly referred to himself as a community organizer rather than as a labor leader and underscored that distinction.

Cesar Chavez wanted his organization to represent not just a union but a larger social movement.

Cesar Chavez personally disliked many of the prominent figures within the American labor movement but, as a pragmatist, recognized the value of working with organized labor groups.

Cesar Chavez opposed the idea of paying wages to those who worked for the union, believing that it would destroy the spirit of the movement.

Cesar Chavez rarely fired people from their positions, but instead made their working situation uncomfortable so that they would resign.

Cesar Chavez felt unable to share the responsibilities of running his movement with others.

Cesar Chavez divided members of movements such as his into three groups: those that achieved what they set out to do, those that worked hard but failed what they set out to do, and those that were lazy.

Cesar Chavez thought that the latter needed to be expelled from the movement.

Cesar Chavez highly valued individuals who were loyal, efficient, and took the initiative.

Cesar Chavez had no money, no political connections, and no experience.

Cesar Chavez was not a particularly dynamic personality and had no special talent as a public speaker.

Cesar Chavez received a range of awards and accolades, which he claimed to hate.

Many ex-members of the UFW took the view that Cesar Chavez had been a poor administrator.

Some critics believed that Cesar Chavez's activism was mobilized largely by the desire for personal gain and ambition.

Bruns noted that Cesar Chavez's movement was "part of the fervor of change [in the United States] of the late 1960s", alongside the civil rights movement and the campaign against the Vietnam War.

The historian Nelson Lichtenstein commented that Cesar Chavez's UFW oversaw "the largest and most effective boycott [in the United States] since the colonists threw tea into Boston Harbor".

Lichtenstein stated that Cesar Chavez had become "an iconic, foundational figure in the political, cultural, and moral history" of the Latino American community.

Cesar Chavez has been described as a "folk saint" of the Mexican-American community.

Cesar Chavez's work has continued to exert influence on later activists.

For instance, in his 2012 article in the Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, Kevin J O'Brien argued that Chavez could be "a vital resource for contemporary Christian ecological ethics".

O'Brien argued that it was both Cesar Chavez's focus on "the moral centrality of human dignity" as well as his emphasis on sacrifice that could be of use by Christians wanting to engage in environmentalist activism.

Cesar Chavez received a range of awards, both during his lifetime and posthumously.

California State University San Marcos' Cesar Chavez Plaza includes a statue to Cesar Chavez.

Cesar Chavez was referenced by Stevie Wonder in the song "Black Man" from the 1976 album Songs in the Key of Life.

The 2014 American film Cesar Chavez, starring Michael Pena as Chavez, covered Chavez's life in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Cesar Chavez received belated full military honors from the US Navy at his graveside on April 23,2015, the 22nd anniversary of his death.

At the start of the presidency of Joe Biden, a bust of Cesar Chavez was placed on a table directly behind the Resolute desk in the Oval Office.