1.

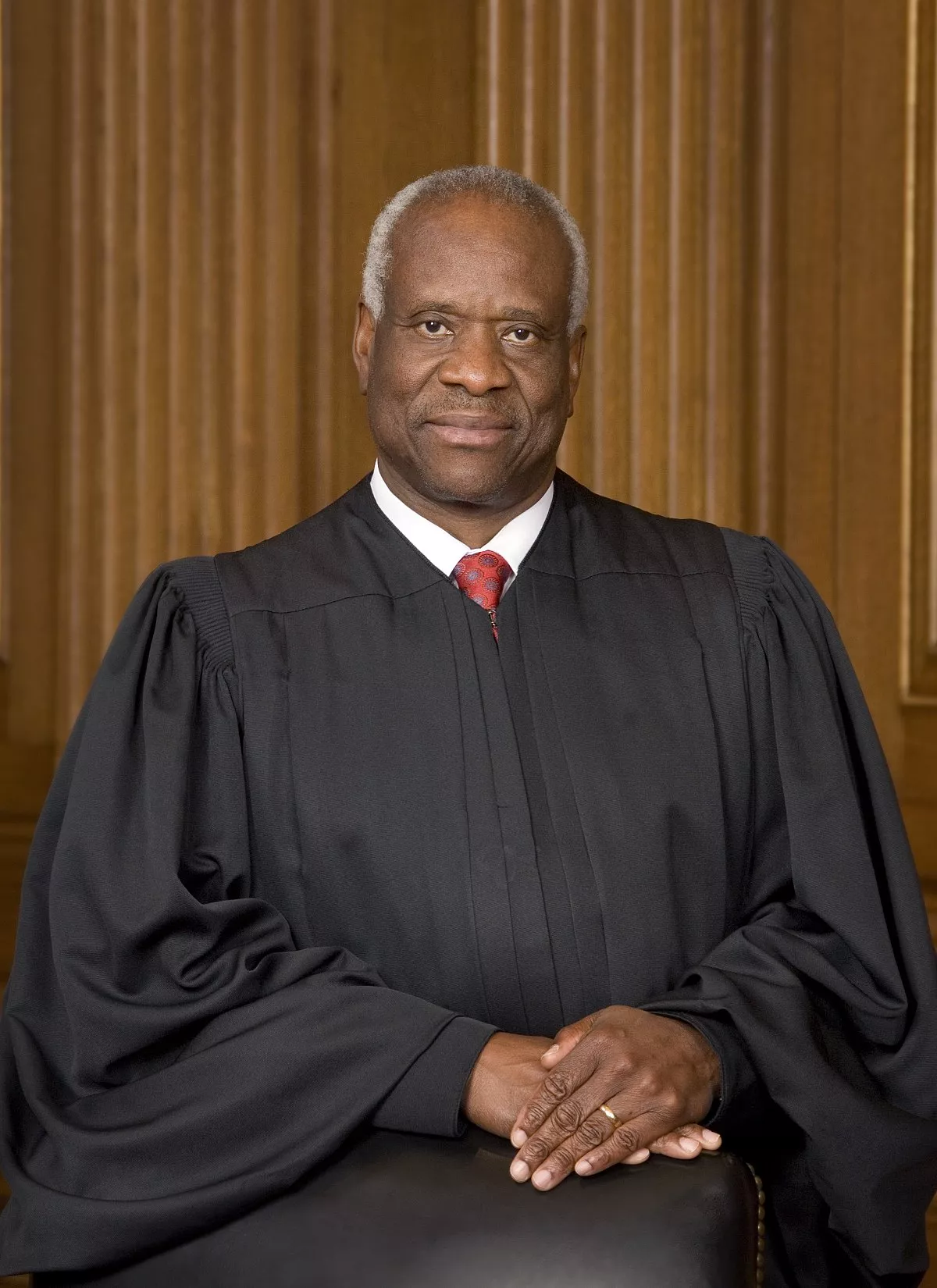

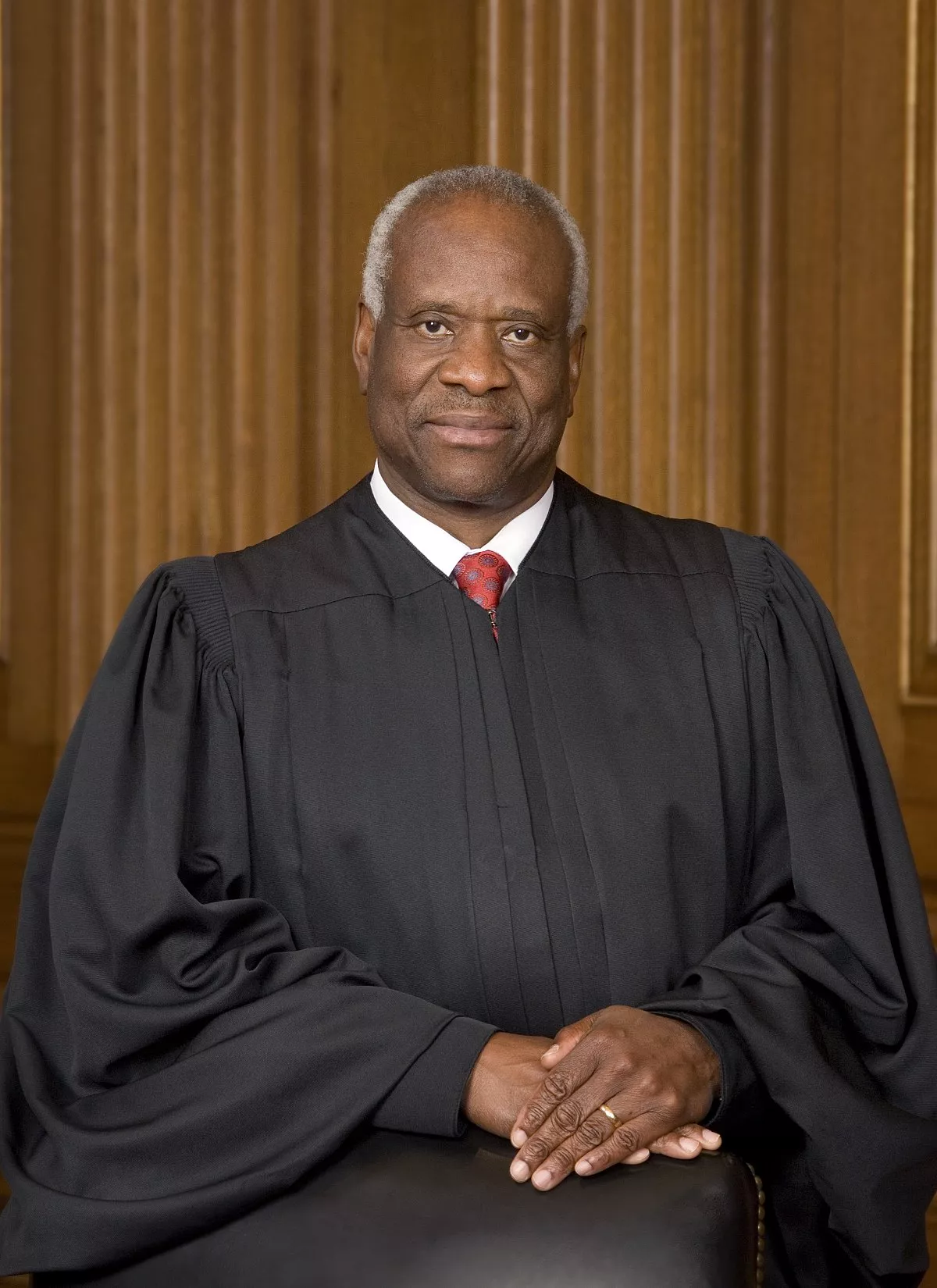

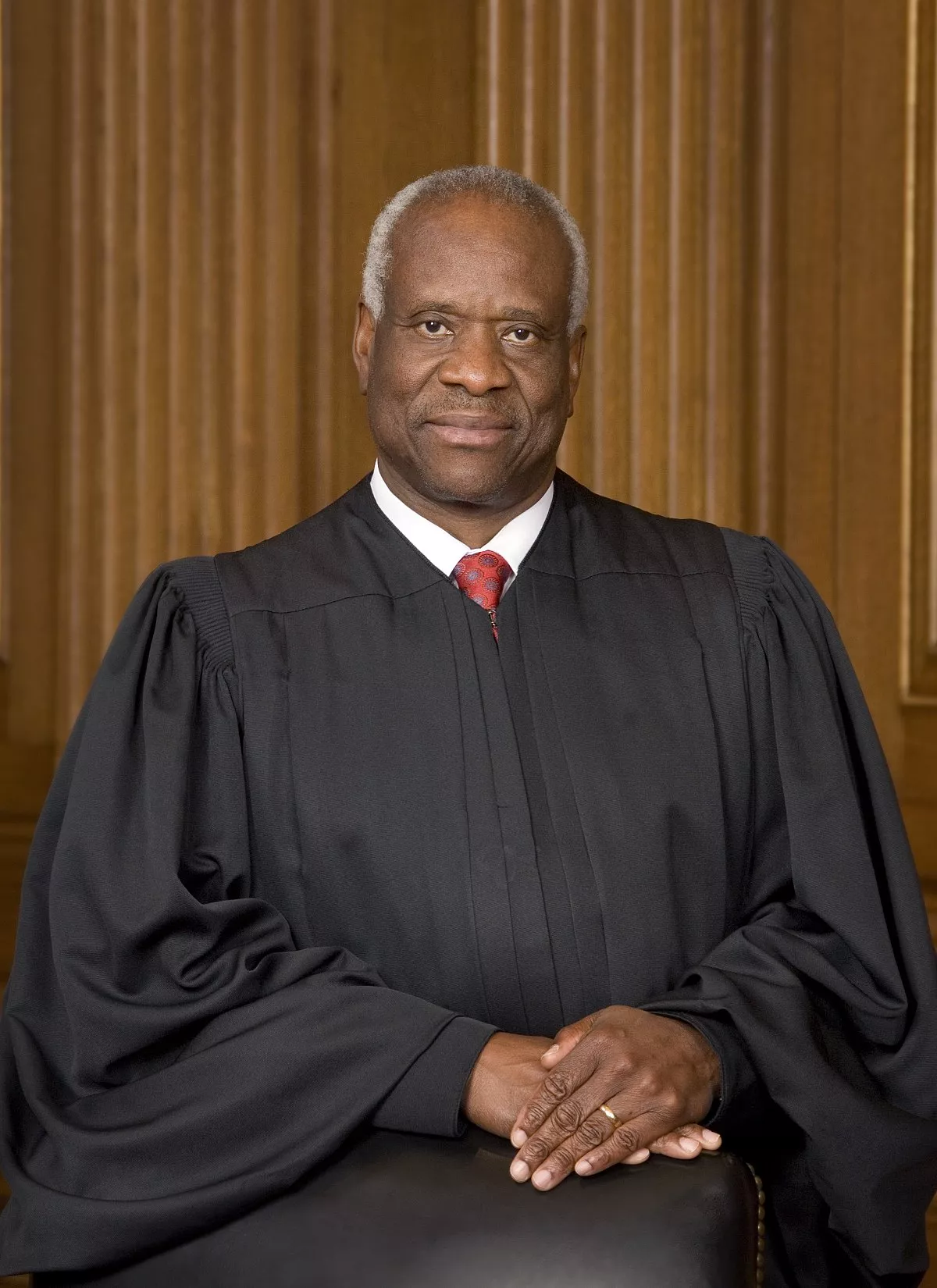

1. Clarence Thomas was born on June 23,1948 and is an American lawyer and jurist who has served since 1991 as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

1.

1. Clarence Thomas was born on June 23,1948 and is an American lawyer and jurist who has served since 1991 as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Clarence Thomas has been the Court's oldest member since Stephen Breyer retired in 2022.

Clarence Thomas graduated with honors from the College of the Holy Cross in 1971 and earned his Juris Doctor in 1974 from Yale Law School.

Clarence Thomas became a legislative assistant to US Senator John Danforth in 1979, and was made Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights at the US Department of Education in 1981.

Clarence Thomas served in that role for 19 months before filling Marshall's seat on the Supreme Court.

Since the death of Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas has been the Court's foremost originalist, stressing the original meaning in interpreting the US Constitution.

Until 2020, Clarence Thomas was known for his silence during most oral arguments, though has since begun asking more questions to counsel.

Clarence Thomas is widely considered to be the Court's most conservative member.

Clarence Thomas was born on June 23,1948, in his parents' wooden shack in Pin Point, Georgia.

Clarence Thomas's earliest known ancestors were slaves named Sandy and Peggy, who were born in the late 18th century and owned by wealthy planter Josiah Wilson of Liberty County.

Clarence Thomas's older sister, Emma, was born in 1946, and his younger brother, Myers, in 1949.

Clarence Thomas initially refused but agreed after his wife threatened to throw him out.

Clarence Thomas has described his grandfather as the person who has influenced his life the most.

Anderson converted to Catholicism and sent Clarence Thomas to be educated at a series of Catholic schools.

Clarence Thomas attended the predominantly black St Pius X High School in Chatham County for two years before transferring to St John Vianney's Minor Seminary on the Isle of Hope, where he was the segregated boarding school's first black student.

Clarence Thomas spent many hours at the Carnegie Library, the only library for Blacks in Savannah before libraries were desegregated in 1961.

When Clarence Thomas was ten years old, Anderson began putting his grandsons to work during the summers, helping him build a house on a plot of farmland he owned, building fences, and doing farm work.

Clarence Thomas believed in hard work and self-reliance, never showed his grandsons affection, beat them frequently according to Leola, and impressed the importance of a good education on them.

Anderson taught Clarence Thomas that "all of our rights as human beings came from God, not man", and that racial segregation was a violation of divine law.

The display of racism moved Clarence Thomas to leave the seminary.

Clarence Thomas thought the church did not do enough to combat racism and resolved to abandon the priesthood.

At a nun's suggestion, Clarence Thomas enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross, an elite Catholic college in Massachusetts, as a sophomore transfer student on a full academic scholarship.

Clarence Thomas was one of the college's first black students, being one of twenty recruited by President John E Brooks in 1968 in a group that included the future attorney Ted Wells, the running back Eddie Jenkins Jr.

Clarence Thomas kept to a strict routine of studying alone and stayed back during holidays to continue working.

Eddie Jenkins, a BSU member, said Clarence Thomas "could turn on a dime and reduce you to intellectual rubble".

Edward P Jones, who lived across from Thomas as a sophomore, reflected that "there was a fierce determination I sensed from him [Thomas], that he was going to get as much as he could and get as far, ultimately, as he could".

Clarence Thomas became acquainted with black separatism, the black Muslim Movement, the black power movement, and displayed a poster of Malcolm X in his dormitory room.

The BSU adopted his idea and Clarence Thomas left campus along with 60 other black students.

Clarence Thomas has credited his protests for his turn toward conservatism and subsequent disillusionment with leftist movements.

Clarence Thomas became a member of Alpha Sigma Nu, the Jesuit honor society, and the Purple Key Society, of which he was the only black member.

Clarence Thomas applied to and was accepted by Yale Law School, Harvard Law School, and the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

That same year, Clarence Thomas entered Yale Law School as one of twelve black students.

Clarence Thomas enrolled in Yale's most difficult courses and became a student of the property law scholar Quintin Johnstone, his favorite professor.

Under Johnstone's supervision, Clarence Thomas completed his law school senior dissertation, a thesis on bar exams, and received honors.

Clarence Thomas graduated from Yale with his Juris Doctor in 1974.

Clarence Thomas thought the law firms "asked pointed questions, unsubtly suggesting that they doubted I was as smart as my grades indicated".

Clarence Thomas moved to Saint Louis to study for the Missouri bar, and was admitted on September 13,1974.

Clarence Thomas remained financially destitute even after leaving Yale, trying unsuccessfully on one occasion to make money by selling his blood at a blood bank, and hoped that by working for Danforth he might later acquire a job in private practice.

Clarence Thomas worked first in the office's criminal appeals division and later in the revenue and taxation division.

Clarence Thomas conducted lawsuits independently, gaining a reputation as a fair but controversial prosecutor.

Years later, after he joined the Supreme Court, Clarence Thomas recalled his position in Missouri as "the best job I've ever had".

When Danforth was elected to the US Senate in 1976, Clarence Thomas left to become an attorney in Monsanto's legal department in Saint Louis.

Clarence Thomas found the job unsatisfying, so left to rejoin Danforth in Washington, DC, as a legislative assistant.

The Senate received the nomination on May 28,1981, and Clarence Thomas was quickly confirmed before the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee on June 19, succeeding Cynthia Brown at the age of 32.

Clarence Thomas held the position for a brief period before James offered him a new position as chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a promotion that Thomas believed, as with his position in the OCR, was because of his race.

Clarence Thomas chaired the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission from 1982 to 1990.

Clarence Thomas announced a reorganization of the EEOC and upgraded its record-keeping under an uncompromising leadership that eschewed racial quotas.

Concerned by the EEOC's limited statutory authority, Clarence Thomas sought to impose criminal penalties for employers who practiced employment discrimination, moving to shift funding towards agency investigators.

The EEOC's lack of the use of goals and timetables drew criticism from civil rights advocates, who lobbied representatives to review the EEOC's practices; Clarence Thomas testified before Congress more than 50 times.

White House Counsel C Boyden Gray and White House Chief of Staff John H Sununu advocated for his nomination, and Judge Laurence Silberman advised Thomas to accept an appointment.

Clarence Thomas gained the support of other African American officials, including former transportation secretary William Coleman, and said that when meeting white Democratic staffers in the United States Senate, he was "struck by how easy it had become for sanctimonious whites to accuse a black man of not caring about civil rights".

Clarence Thomas developed cordial relationships during his 19 months on the federal court, including with Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

At age 42, Clarence Thomas was the DC Circuit's youngest judge.

Clarence Thomas ruled in 145 cases, many of which concerned criminal matters.

When Justice William Brennan retired from the Supreme Court in July 1990, Clarence Thomas was Bush's favorite among the five candidates on his shortlist for the position.

Abortion-rights groups, including the National Abortion Rights Action League and the NOW, were concerned that Thomas would be among those to overrule Roe v Wade.

On July 31,1991, the board of directors of the NAACP voted against endorsing Clarence Thomas, announcing their opposition to his confirmation the same day.

Opponents of Clarence Thomas's nomination saw the assessment as indicating that he was unfit for the Court.

Clarence Thomas testified for 25 hours, the second-longest of any Supreme Court nominee.

Clarence Thomas was reticent when answering senators' questions, recalling what had happened to Robert Bork when Bork expounded on his judicial philosophy during his confirmation hearings four years earlier.

Clarence Thomas said he regarded natural law as a "philosophical background" to the Constitution.

Hill was raised in Oklahoma and, like Clarence Thomas, graduated from Yale Law School.

Hill requested to the staff of Senator Joe Biden, the chair of the committee, that her allegations be made anonymously if she chose to testify and that Clarence Thomas not be informed of them, which Biden declined.

Clarence Thomas recalled that Thomas told Hill in an elevator at the EEOC that he would ruin her career if she spoke about his behavior.

Clarence Thomas told the Committee that he would not allow any questions about "what goes on in the most intimate parts of my private life or the sanctity of my bedroom" so as not to "provide the rope for my own lynching".

Clarence Thomas's testimony included graphic details, and some senators questioned her aggressively.

Clarence Thomas again denied the allegations and was prompted by Senator Orrin Hatch's questioning to launch a speech that criticized the proceeding as a "high-tech lynching for uppity blacks".

Clarence Thomas received the votes of 41 Republicans and 11 Democrats, while 46 Democrats and two Republicans voted to reject his nomination.

The 99 days during which Clarence Thomas's nomination was pending in the Senate was the second-longest of the 16 nominees receiving a final vote since 1975, second only to Bork's 108 days.

The vote to confirm Clarence Thomas was the narrowest margin for approval in more than 100 years.

Clarence Thomas's first set of law clerks included future judges Gregory Katsas and Gregory Maggs and US Ambassador Christopher Landau.

Clarence Thomas aligned himself with Justice Antonin Scalia, with whom he shared an originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, and sided with him in 92 percent of cases during his first 13 years on the bench.

Clarence Thomas's appointment represented a decline in the Court's liberal wing, which then comprised only Justices John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun.

Clarence Thomas became the subject of intense media criticism for his decisions, including from figures that supported his appointment.

Clarence Thomas formed a friendship with Justice Byron White, with whom he shared multiple interests, and found support from Justice David Souter.

Clarence Thomas is a proponent of original meaning, incorporating what had been Scalia's narrower approach to the doctrine and the original intent of the Framers of the Constitution, including those espoused in the Declaration of Independence.

Clarence Thomas has been the most-willing of all justices on the Court to overrule precedent; according to Scalia, "he does not believe in stare decisis, period".

In 2016, Clarence Thomas wrote nearly twice as many opinions as any other justice.

Clarence Thomas has been called the most conservative member of the Supreme Court, though others gave Scalia that designation while they served on the Court together.

Clarence Thomas was the most senior associate justice by that time.

Clarence Thomas believes the Court should not follow erroneous precedent, a view not currently held by other justices.

Clarence Thomas has called to reconsider New York Times Co.

In 2019, The New York Times reported that data gathered by political scientist Stephen L Wasby of the University at Albany found that Thomas wrote "more than 250 concurring or dissenting opinions seriously questioning precedents, calling for their reconsideration or suggesting that they be overruled".

Clarence Thomas explicitly disavowed the concept of reliance interests as justification for adhering to precedent.

Clarence Thomas has supported a broad interpretation of executive power and has theorized about its constitutional aspects.

Clarence Thomas wrote in Hamdi that the president does not have the singular authority to detain a citizen who was captured while in enemy service.

In Zivotofsky v Kerry, Thomas relied on the Articles of Confederation for his opinion.

Clarence Thomas wrote, "the President is not confined to those powers expressly identified in [the Constitution]", concluding that residual foreign affairs were vested in the president, not Congress.

Rather than finding the original intent or original understanding, Clarence Thomas wrote in the case that he sought the "understanding of executive power [that] prevailed in America" at the time of the founding.

On September 24,1999, Thomas delivered the Dwight D Opperman Lecture at Drake University Law School on "Why Federalism Matters", saying that it was an essential safeguard to protect "individual liberty and the private ordering of our lives".

Clarence Thomas asserted that federalism enhances self-government, protects individual liberty by separating political power, and checks federal authority.

Clarence Thomas argued that states could impose term limits on members of Congress, as state citizens are "the ultimate source of the Constitution's authority".

That same year, Thomas concurred in United States v Lopez, which invalidated the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 for going beyond the Commerce Clause.

Clarence Thomas opined that the Court had deviated "from the original understanding of the Commerce Clause" and that the substantial effects test, "if taken to its logical extreme, would give Congress a 'police power' over all aspects of American life".

Clarence Thomas's dissent, joined by Scalia, argued that the clause allows Congress only to execute enumerated powers.

In Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No 1 v Holder, Thomas was the sole dissenter, voting to throw out Section Five of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Congress had reauthorized Section Five in 2006 for another 25 years, but Clarence Thomas said the law was no longer necessary, stating that the rate of black voting in seven Section Five states was higher than the national average.

Clarence Thomas has generally written opinions in favor of protections for free speech.

Clarence Thomas has voted in favor of First Amendment claims in cases involving issues including campaign contributions and commercial speech.

In Rubin, Clarence Thomas was joined unanimously in ruling unconstitutional a 1935 federal law that prohibited beer labels from disclosing alcohol content.

Clarence Thomas similarly concurred the next year in 44 Liquormart v Rhode Island, which struck down a state law that banned the advertisement of prices of alcoholic beverages.

Clarence Thomas joined Justice Stephen Breyer's majority opinion in the case, but wrote separately to call against the framework established in the previous campaign finance case of Buckley v Valeo :.

Clarence Thomas has made public his belief that all limits on federal campaign contributions are unconstitutional and should be struck down.

In Citizens United v FEC, Thomas joined the majority but dissented in part, arguing that the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act's disclaimer and disclosure requirements were unconstitutional.

Clarence Thomas reinforced his defense of anonymous speech in Doe v Reed, writing that the First Amendment protects "political association" by means of signing a petition.

Clarence Thomas criticized the majority for relying on "vague considerations" and wrote that historically schools could discipline students in similar situations.

Since 2010, Clarence Thomas has dissented from denial of certiorari in several Second Amendment cases.

Clarence Thomas voted to grant certiorari in Friedman v City of Highland Park, which upheld bans on certain semi-automatic rifles; Jackson v San Francisco, which upheld trigger lock ordinances similar to those struck down in Heller; Peruta v San Diego County, which upheld restrictive concealed carry licensing in California; and Silvester v Becerra, which upheld waiting periods for firearm purchasers who have already passed background checks and already own firearms.

Clarence Thomas was joined by Scalia in the first two cases, and by Gorsuch in Peruta.

Clarence Thomas dissented in Georgia v Randolph, which prohibited warrantless searches that one resident approves and the other opposes, arguing that the Court's decision in Coolidge v New Hampshire controlled the case.

In cases involving schools, Clarence Thomas has advocated greater respect for the doctrine of in loco parentis, which he defines as "parents delegat[ing] to teachers their authority to discipline and maintain order".

All the justices except Clarence Thomas concluded that the search violated the Fourth Amendment.

Clarence Thomas wrote, "It is a mistake for judges to assume the responsibility for deciding which school rules are important enough to allow for invasive searches and which rules are not" and "reasonable suspicion that Redding was in possession of drugs in violation of these policies, therefore, justified a search extending to any area where small pills could be concealed".

Clarence Thomas dissented, arguing that the Speedy Trial Clause's purpose was to prevent "'undue and oppressive incarceration' and the 'anxiety and concern accompanying public accusation'" and that the case implicated neither.

Clarence Thomas cast the case instead as "present[ing] the question [of] whether, independent of these core concerns, the Speedy Trial Clause protects an accused from two additional harms: prejudice to his ability to defend himself caused by the passage of time; and disruption of his life years after the alleged commission of his crime".

Clarence Thomas dissented from the court's decision to, as he saw it, answer the former in the affirmative.

Clarence Thomas's opinion was criticized by the seven-member majority, which wrote that, by comparing physical assault to other prison conditions such as poor prison food, it ignored "the concepts of dignity, civilized standards, humanity, and decency that animate the Eighth Amendment".

In United States v Bajakajian, Thomas joined with the Court's liberal justices to write the majority opinion declaring a fine unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment.

Clarence Thomas noted that the case required a distinction to be made between civil forfeiture and a fine exacted with the intention of punishing the respondent.

Clarence Thomas found that the forfeiture in this case was clearly intended as a punishment at least in part, was "grossly disproportional" and violated the Excessive Fines Clause.

Clarence Thomas believes the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids consideration of race, such as race-based affirmative action or preferential treatment.

Clarence Thomas filed a concurring opinion, which he read from the bench, a rare practice for Supreme Court justices.

Clarence Thomas has contended that the Constitution does not address abortion.

Concurring, Clarence Thomas asserted that the court's abortion jurisprudence had no basis in the Constitution but that the court had accurately applied that jurisprudence in rejecting the challenge.

In December 2018, Clarence Thomas dissented when the Court voted not to hear cases brought by Louisiana and Kansas to deny Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood.

Alito and Gorsuch joined Clarence Thomas's dissent, arguing that the Court was "abdicating its judicial duty".

In February 2019, Clarence Thomas joined three of the Court's other conservative justices in voting to reject a stay to temporarily block a law restricting abortion in Louisiana.

In Romer v Evans, Thomas joined Scalia's dissenting opinion arguing that Amendment Two to the Colorado State Constitution did not violate the Equal Protection Clause.

In Lawrence v Texas, Thomas issued a one-page dissent in which he called the Texas statute prohibiting sodomy "uncommonly silly", a phrase originally used by Justice Potter Stewart.

Clarence Thomas saw the issue as a matter for states to decide for themselves.

In October 2020, Thomas joined the other justices in denying an appeal from Kim Davis, a county clerk who refused to give marriage licenses to same-sex couples, but wrote a separate opinion reiterating his dissent from Obergefell v Hodges and expressing his belief that it was wrongly decided.

Clarence Thomas has given many reasons for his silence, including self-consciousness about how he speaks, a preference for listening to those arguing the case, and difficulty getting in a word.

Clarence Thomas took a more active role in questioning when the Supreme Court shifted to holding teleconferenced arguments in May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the justices took turns asking questions in order of seniority.

Since the court resumed in-person oral arguments at the beginning of the 2021 term, the justices agreed to allow Clarence Thomas to ask the first question of each lawyer following their opening statements.

Virginia "Ginni" Clarence Thomas has remained active in conservative politics, serving as a consultant to The Heritage Foundation and as founder and president of Liberty Central.

Also in 2011,74 Democratic members of the House of Representatives wrote that Justice Clarence Thomas should recuse himself on cases regarding the Affordable Care Act because of "appearance of a conflict of interest" based on his wife's work.

In March 2022, texts between Ginni Clarence Thomas and Trump's chief of staff Mark Meadows from 2020 were turned over to the Select Committee on the January 6 Attack.

The texts show Ginni Clarence Thomas repeatedly urging Meadows to overturn the election results and repeating conspiracy theories about ballot fraud.

Clarence Thomas was reconciled to the Catholic Church in the mid-1990s.

In 1975, when Clarence Thomas read economist Clarence Thomas Sowell's Race and Economics, he found an intellectual foundation for his philosophy.

Clarence Thomas acknowledges "some very strong libertarian leanings", though he does not consider himself a libertarian.

Clarence Thomas has said novelist Richard Wright is the most influential writer in his life; Wright's books Native Son and Black Boy "capture[d] a lot of the feelings that I had inside that you learn how to repress".

In 2016, Moira Smith, vice-president and general counsel of a natural gas distributor in Alaska, said that Clarence Thomas groped her buttocks at a dinner party in 1999.

Clarence Thomas was a Truman Foundation scholar helping the director of the foundation set up for a dinner party honoring Thomas and David Adkins.

Norma Stevens, who attended the event, said that the incident "couldn't have happened" because Clarence Thomas was never alone, as he was the guest of honor.

In 2004, the Los Angeles Times reported that Clarence Thomas had accepted gifts from Harlan Crow, a wealthy Dallas-based real estate investor and prominent Republican donor, including a Bible that once belonged to abolitionist Frederick Douglass and a bust of Abraham Lincoln.

Also that year, the advocacy group Common Cause reported that between 2003 and 2007, Clarence Thomas failed to disclose $686,589 in income his wife earned from The Heritage Foundation, instead reporting "none" where "spousal noninvestment income" would be reported on his Supreme Court financial disclosure forms.

The next week, Clarence Thomas said the disclosure of his wife's income had been "inadvertently omitted due to a misunderstanding of the filing instructions".

Clarence Thomas did not report the payments on his financial disclosure forms, while ethics law experts said that they were required to be disclosed as gifts.

Mark Paoletta, a longtime friend of Clarence Thomas, said that Crow paid for one year each at Hidden Lake and Randolph-Macon Academy, which ProPublica estimated to be worth around $100,000.

The documents the newspaper reviewed did not indicate the nature of the work Clarence Thomas did for the Judicial Education Project or Conway's company.

Clarence Thomas had previously said that he "had scrimped and saved to afford the motor coach", according to the Times, and a friend, Armstrong Williams, said that Clarence Thomas had told him that "he saved up all his money to buy it".

In June 2024, Clarence Thomas filed an amendment to his financial disclosure report for 2019 to include information he had "inadvertently omitted".

Clarence Thomas did not report travel to and from the destinations on private jets or the nine-day cruise on Crow's superyacht.

On December 21,2024, Democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee released a report revealing that Clarence Thomas had taken an additional two trips in 2021 paid for by Crow.

Fix the Court released an analysis showing that, over the 20 years beginning in 2004, Clarence Thomas had accepted gifts worth $4.2 million, based on reporting by ProPublica and others.

Clarence Thomas was awarded the 1992 Horatio Alger Award by the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

In 2001, Clarence Thomas was awarded the Francis Boyer Award presented by the American Enterprise Institute.

In 2012, Clarence Thomas received an honorary degree from the College of the Holy Cross, his alma mater.

Clarence Thomas was a member of the college's board of trustees in 1990, and from 2004 to 2006.