1.

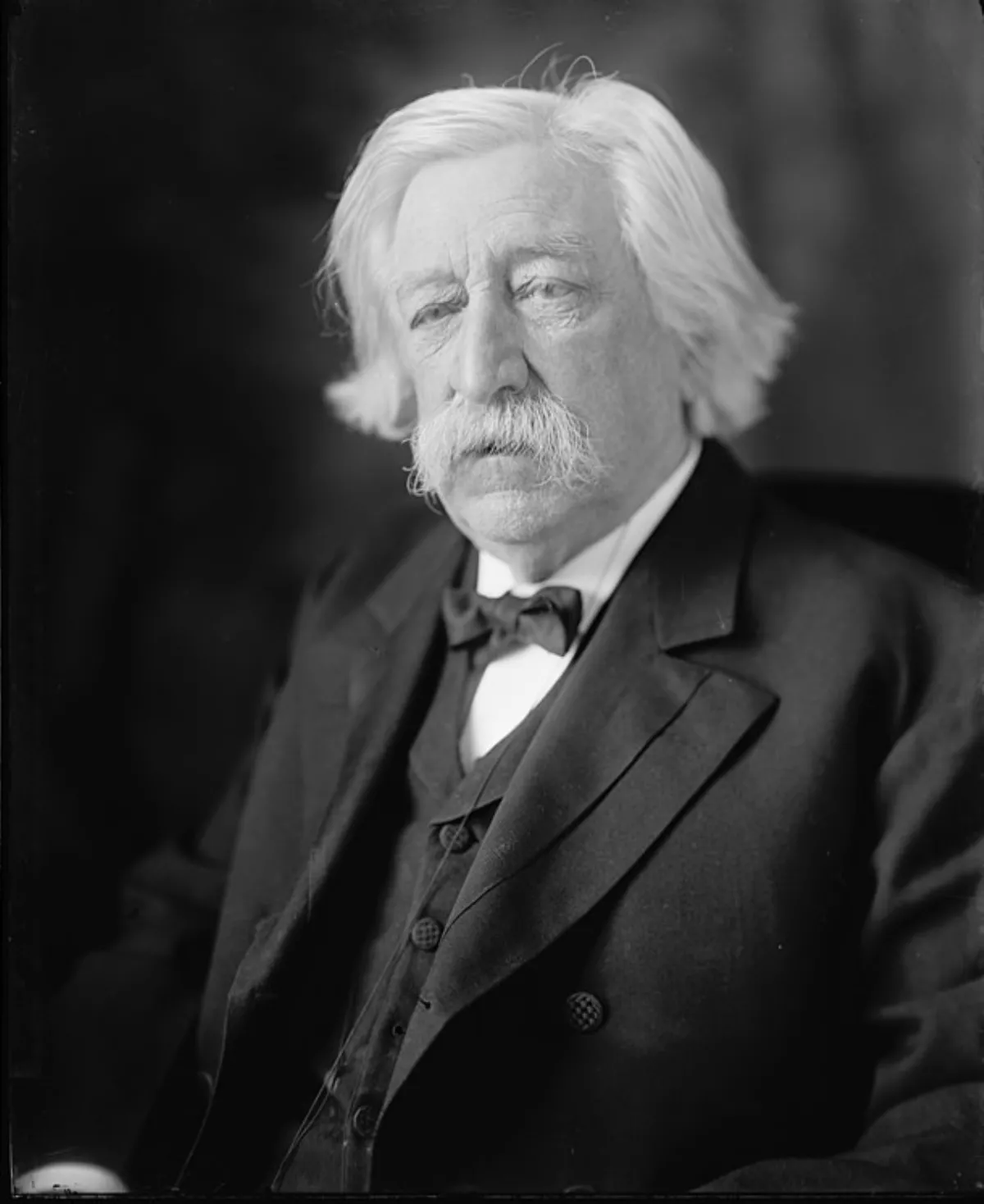

1. Melville Weston Fuller was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910.

1.

1. Melville Weston Fuller was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910.

Melville Fuller wrote major opinions on the federal income tax, the Commerce Clause, and citizenship law, and he took part in important decisions about racial segregation and the liberty of contract.

Melville Fuller became a prominent attorney in Chicago and was a delegate to several Democratic National Conventions.

Melville Fuller declined three separate appointments offered by President Grover Cleveland before accepting the nomination to succeed Morrison Waite as chief justice.

Melville Fuller served as chief justice until his death in 1910, gaining a reputation for collegiality and able administration.

Melville Fuller's jurisprudence was conservative, focusing strongly on states' rights, limited federal power, and economic liberty.

In Lochner v New York, Fuller agreed with the majority that the Constitution forbade states from enforcing wage-and-hour restrictions on businesses, contending that the Due Process Clause prevents government infringement on one's liberty to control one's property and business affairs.

Melville Fuller argued in the Insular Cases that residents of the territories are entitled to constitutional rights, but he dissented when, in United States v Wong Kim Ark, the majority ruled in favor of birthright citizenship.

Many of Melville Fuller's decisions did not stand the test of time.

Melville Fuller's maternal grandfather, Nathan Weston, served on the Supreme Court of Maine, and his paternal grandfather was a probate judge.

Three months after Melville Fuller was born, his mother sued successfully for divorce on grounds of adultery; she and her children moved into Judge Weston's home.

In 1849, the sixteen-year-old Melville Fuller enrolled at Bowdoin College, from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1853.

Melville Fuller studied law in an uncle's office before spending six months at Harvard Law School.

Melville Fuller was admitted to the Maine bar in 1855 and clerked for another uncle in Bangor.

Melville Fuller was elected to Augusta's common council in March 1856, serving as the council's president and as the city solicitor.

Melville Fuller accepted a position with a local law firm, and he became involved in politics.

Melville Fuller opposed both abolitionists and secessionists, arguing instead for compromise.

Melville Fuller campaigned for Stephen A Douglas both in his successful 1858 Senate campaign against Abraham Lincoln and in his unsuccessful bid against Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election.

Melville Fuller was elected as a Democratic delegate to the failed 1862 Illinois state constitutional convention.

Melville Fuller helped develop a gerrymandered system for congressional apportionment, and he joined his fellow Democrats in supporting provisions that prohibited African-Americans from voting or settling in the state.

Melville Fuller advocated for court reform and for banning banks from printing of paper money.

In November 1862, Melville Fuller was narrowly elected to a seat in the Illinois House of Representatives as a Democrat.

Melville Fuller spoke in opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation, arguing that it violated state sovereignty.

Melville Fuller supported the Corwin Amendment, which would have prevented the federal government from outlawing slavery.

Melville Fuller opposed Lincoln's decision to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, believing it violated civil liberties.

The frustrated Melville Fuller never sought legislative office again, although he continued taking part in Democratic party politics.

Melville Fuller maintained a successful legal practice, arguing on behalf of many corporations and businessmen.

Melville Fuller represented the city of Chicago in a land dispute with the Illinois Central Railroad.

The matter returned to the courts, where Melville Fuller argued that only the local congregation had the right to remove Cheney.

Melville Fuller remained involved in the politics of the Democratic Party, serving as a delegate to the party's national conventions in 1872,1876, and 1880.

Melville Fuller firmly opposed the printing of paper money, and he spoke out against the Supreme Court's 1884 decision in Juilliard v Greenman upholding Congress's power to issue it.

Melville Fuller was a supporter of states' rights and generally advocated for limited government.

Melville Fuller strongly supported President Grover Cleveland, a fellow Democrat, who agreed with many of his views.

Melville Fuller considered Vermont native Edward J Phelps, the ambassador to the United Kingdom, but the politically influential Irish-American community, which viewed him as an Anglophile, opposed him.

Melville Fuller, who had become a confidant of Cleveland, encouraged the President to appoint John Scholfield, who served on the Illinois Supreme Court.

Cleveland offered the position to Scholfield, but he declined, apparently because his wife was too rustic for urban life in Washington, DC Melville Fuller was considered because of the efforts of his friends, many of whom had written letters to Cleveland in support of him.

At fifty-five years old, Melville Fuller was young enough for the position, and Cleveland approved of his reputation and political views.

Public reaction to Melville Fuller's nomination was mixed: Some newspapers lauded his character and professional career, while others criticized his comparative obscurity and his lack of experience in the federal government.

Some Illinois Republicans, including Lincoln's son Robert, came to Melville Fuller's defense, arguing that his actions were imprudent but not an indicator of disloyalty.

Melville Fuller's detractors claimed he would reverse the Supreme Court's ruling in the recent legal-tender case of Juilliard; his defenders replied he would be faithful to precedent.

Several prominent Republican senators, including William M Evarts of New York, William Morris Stewart of Nevada, and Edmunds, spoke against the nomination, arguing that Fuller was a disloyal Copperhead who would misinterpret the Reconstruction Amendments and roll back the progress made by the Civil War.

Melville Fuller accused Edmunds of hypocrisy and insincerity, saying he was simply resentful that Phelps had not been chosen.

Melville Fuller served twenty-two years as chief justice, remaining in the center chair until his death in 1910.

Melville Fuller successfully maintained more-or-less cordial relationships among the justices, many of whom had large egos and difficult tempers.

Melville Fuller himself wrote few dissents, disagreeing with the majority in only 2.3 percent of cases.

Melville Fuller was the first chief justice to lobby Congress directly in support of legislation, successfully urging the adoption of the Circuit Courts of Appeals Act of 1891.

Melville Fuller tended to use this power modestly, often assigning major cases to other justices while retaining duller ones for himself.

Justice Felix Frankfurter opined that Fuller was "not an opinion writer whom you read for literary enjoyment", while the scholar G Edward White characterized his style as "diffident and not altogether successful".

In 1893, Cleveland offered to appoint Melville Fuller to be secretary of state.

Melville Fuller declined, saying he enjoyed his work as chief justice and contending that accepting a political appointment would harm the Supreme Court's reputation for impartiality.

Melville Fuller's health declined after 1900, and scholar David Garrow suggests that his "growing enfeeblement" inhibited his work.

Melville Fuller favored states' rights over federal power, attempting to prevent the national government from asserting broad control over economic matters.

Melville Fuller took no interest in preventing racial inequality, although his views on other civil rights issues were less definitive.

Much of Melville Fuller's jurisprudence has not stood the test of time: many of his decisions have been reversed by Congress or overruled by later Supreme Court majorities.

The majority opinion, written by Melville Fuller, held that the Framers intended the term "direct tax" to include property and that income was itself a form of property.

Melville Fuller was suspicious of attempts to assert broad federal power over interstate commerce.

Melville Fuller feared that a broader interpretation of the Commerce Clause would impinge upon states' rights, and he thus held the Sugar Trust could only be broken up by the states in which it operated.

Melville Fuller dissented, joining opinions written by Justices Edward Douglass White and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Melville Fuller dissented from the Court's 1903 decision in Champion v Ames, in which five justices upheld a federal ban on transporting lottery tickets across state lines.

Melville Fuller feared that the law violated the principles of federalism and states' rights protected by the Tenth Amendment.

Melville Fuller maintained that bakers could protect their own health, arguing that the law was in fact a labor regulation in disguise.

The Fuller Court was not exclusively hostile to labor regulation: in Muller v Oregon, for example, it unanimously upheld an Oregon law capping women's working hours at ten hours a day.

Melville Fuller's attorneys petitioned the Supreme Court for relief, arguing that racial bias had tainted the jury pool and that the threat of mob violence made the venue unfair.

Melville Fuller, writing for a five-justice majority, found Shipp and several other defendants guilty of contempt.

The Melville Fuller Court was no more liberal in other cases involving race: to the contrary, it curtailed even the limited progress toward equality made under Melville Fuller's predecessors.

For instance, Fuller joined the unanimous majority in Williams v Mississippi, which rejected a challenge to poll taxes and literacy tests that in effect disenfranchised Mississippi's African-American population.

Melville Fuller, writing for the four dissenters, argued that Congress had no power to hold the territories "like a disembodied shade" free from all constitutional limits.

Melville Fuller contended that the Constitution could not tolerate unrestricted congressional power over the territories, writing that it rejected that proposition in a way "too plain and unambiguous to permit its meaning to be thus influenced".

Melville Fuller's opinion was in line both with his strict-constructionist views and his party's opposition to American imperialism.

Melville Fuller penned a dissent, in which he maintained that Congress had no authority to order the confiscation of property.

Ultimately, Melville Fuller's position was vindicated: Congress later passed a joint resolution restoring the church's property.

Melville Fuller was rarely amenable to the claims of Chinese immigrants.

Three justices, including Melville Fuller, dissented, arguing that aliens were at least entitled to some Constitutional protections.

Melville Fuller was married twice, first to Calista Reynolds, whom he wed in 1858.

Melville Fuller's rulings were often favorable to corporations, and some scholars have claimed that the Melville Fuller Court was biased towards big business and against the working class.

Yet the Melville Fuller Court's jurisprudence was a key source of the legal academy's criticism.

Melville Fuller noted that Fuller and his fellow justices rendered rulings that generally conformed with contemporaneous public opinion.

Lawrence Reed of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy wrote in 2006 that Melville Fuller was "a model Chief Justice", favorably citing his economic jurisprudence.

George Skouras, writing in 2011, rejected the ideas of Ely, Ackerman, and Gillman, agreeing instead with the Progressive argument that the Melville Fuller Court favored corporations over vulnerable Americans.

Melville Fuller's legacy came under substantial scrutiny amidst racial unrest in 2020, with many condemning him for his vote in Plessy.

In 2013, a statue of Melville Fuller, donated by a cousin, was installed on the lawn in front of Augusta's Kennebec County Courthouse.