1.

1. Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen is best known today for his 1971 magnum opus The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, in which he argued that all natural resources are irreversibly degraded when put to use in economic activity.

1.

1. Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen is best known today for his 1971 magnum opus The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, in which he argued that all natural resources are irreversibly degraded when put to use in economic activity.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen graduated from Sorbonne University in 1930 with a PhD in mathematical statistics with the highest honors.

Early in his life, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was the student and protege of Joseph Schumpeter, who taught that irreversible evolutionary change and 'creative destruction' are inherent to capitalism.

Later in life, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was the teacher and mentor of Herman Daly, who then went on to develop the concept of a steady-state economy to impose permanent government restrictions on the flow of natural resources through the economy.

In spite of such appreciation, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was never awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics, although benefactors from his native Romania were lobbying for it on his behalf.

The inability or reluctance of most mainstream economists to recognise Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's work has been ascribed to the fact that much of his work reads like applied physics rather than economics, as this latter subject is generally taught and understood today.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's work was blemished somewhat by mistakes caused by his insufficient understanding of the physical science of thermodynamics.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's father, of Greek descent, was an army officer, and his mother, an ethnic Romanian, was a sewing teacher at a girls school.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's stay in Paris broadened his field of study well beyond pure mathematics.

Emile Borel, one of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's professors, thought so highly of the dissertation that he had it published in full as a special issue of a French academic journal.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen made arrangements to lodge with the family of a young Englishman he had met in Paris and left for England in 1931.

When he approached Pearson and the English university system, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was amazed with the informality and openness he found.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was now in a stimulating intellectual environment with weekly evening gatherings and informal academic discussions, where Schumpeter himself presided as the 'ringmaster' of the circle.

In Schumpeter, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen had found a competent and sympathetic mentor.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen managed to obtain a modest stipend for himself and his wife Otilia that enabled them to travel about the country, journeying as far as California.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen offered Georgescu-Roegen a position with the economics faculty, and asked him to work with him on an economics treatise as a joint effort, but Georgescu-Roegen declined.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen wanted to go back to Romania in order to serve his backward fatherland that had sponsored most of his education so far; besides, his return was expected at home.

In spring 1936, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen left the US His voyage back to Romania came to last almost a year in itself, as he paid a long visit to Friedrich Hayek and John Hicks at the London School of Economics on the way home.

From 1937 to 1948, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen lived in Romania, where he witnessed all the turmoil of World War II and the subsequent rise to power of the communists in the country.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen became vice-director of the Central Statistical Institute, responsible for compiling data on the country's foreign trade on a daily basis; he served on the National Board of Trade, settling commercial agreements with the major foreign powers; he even participated in the diplomatic negotiations concerning the reassignment of Romania's national borders with Hungary.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen engaged himself in politics and joined the pro-monarchy National Peasants' Party.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen put a persuasive effort into this work and was elevated to the higher ranks of the party, becoming member of the party's National Council.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen did only little academic work during this period of his life.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen accepted the offer and moved to Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee in 1949.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen remained at Vanderbilt until his retirement in 1976 at age 70.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen held numerous visiting appointments and research fellowships across the continents, and served as editor of a range of academic journals, including the Econometrica.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen received several academic honours, including the distinguished Harvie Branscomb Award, presented in 1967 by his employer, Vanderbilt University.

One other important result of the cooperation was the publication of the pointed and polemical article on Energy and Economic Myths, where Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen took issue with mainstream economists and various other debaters.

Later, the cooperation with the club waned: Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen reproached the club for not adopting a definite anti-growth political stance; he was sceptical of the club's elitist and technocratic fashion of attempting to monitor and guide global social reality by building numerous abstract computer simulations of the world economy, and then publish all the findings to the general public.

When Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen delivered a lecture at the University of Geneva in Switzerland in 1974, he made a lasting impression on the young and newly graduated French historian and philosopher Jacques Grinevald.

Apart from his involvement with the Club of Rome and a few European scholars, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen remained a solitary man throughout the years at Vanderbilt.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen rarely discussed his ongoing work with colleagues and students, and he collaborated in very few joint projects during his career.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen corresponded extensively with his few friends and former colleagues.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen lived long enough to survive the communist dictatorship in Romania he had fled earlier in his life.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen even received some late recognition from his fatherland: In the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent Romanian Revolution in 1989, Georgescu-Roegen was elected to the Romanian Academy in Bucharest.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen believed he had long been running against a current.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was becoming rather deaf, and complications caused by his diabetes rendered him unable to climb stairs.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen cut off all human contact, even to those of his former colleagues and students who appreciated his contribution to economics.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen died bitter and lonely in his home at the age of 88.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen found that two of his other main sources of inspiration, namely Karl Pearson and Albert Einstein, had a largely Machian outlook.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen was critical of the increasing use of abstract algebraic formalism grounded in no facts of social reality.

Hence, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen engages himself in an intellectual battle with two fronts.

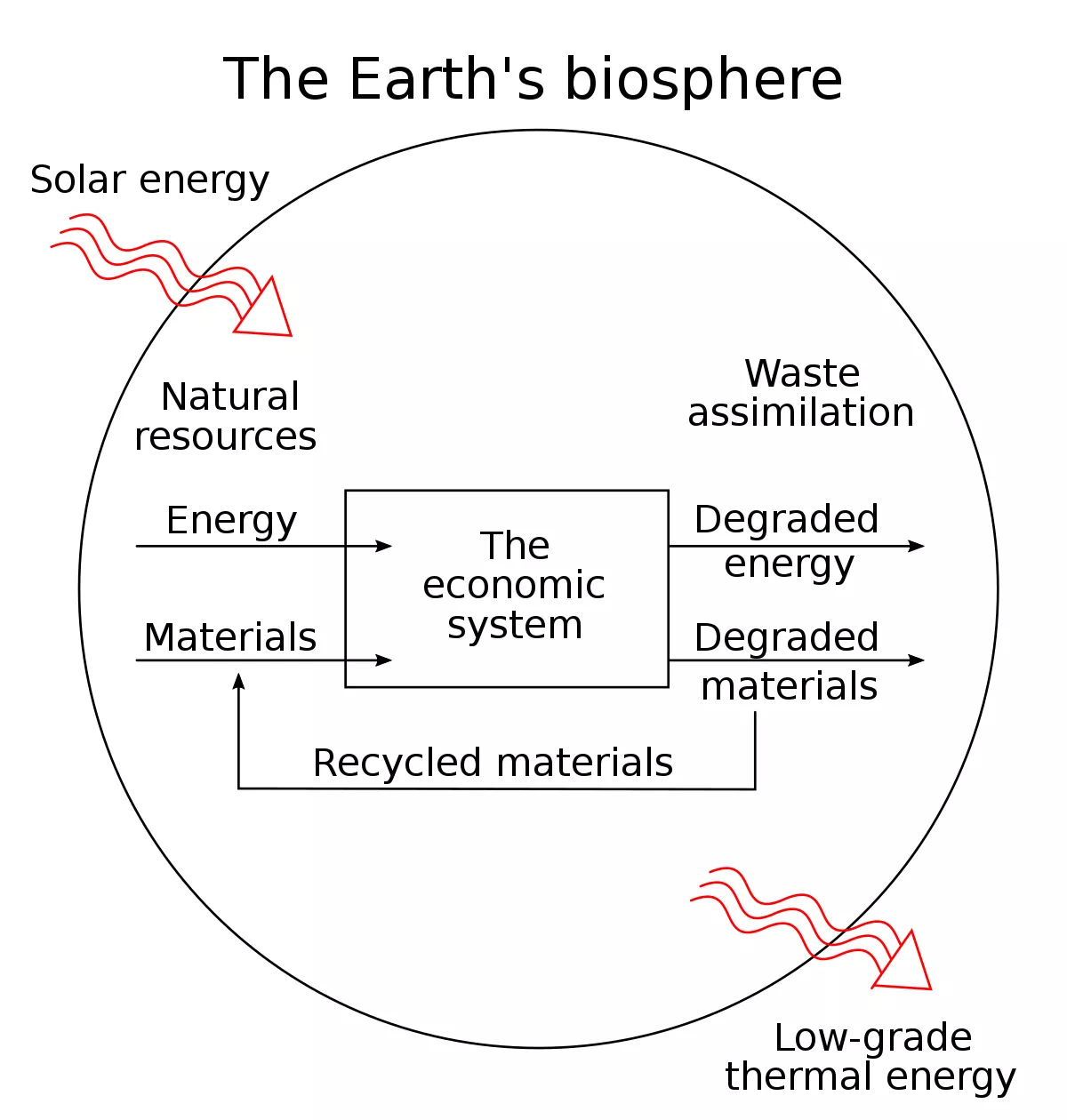

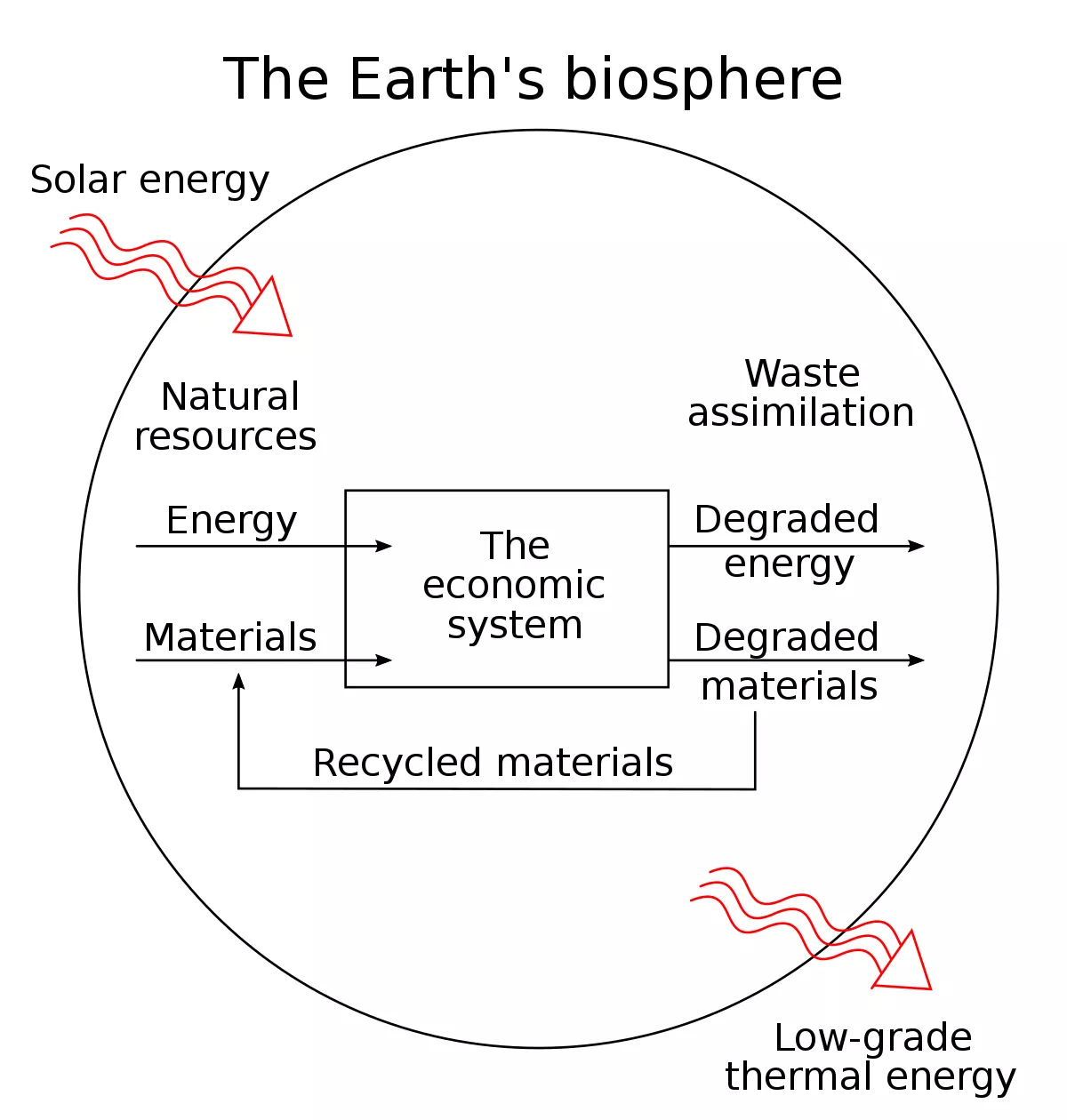

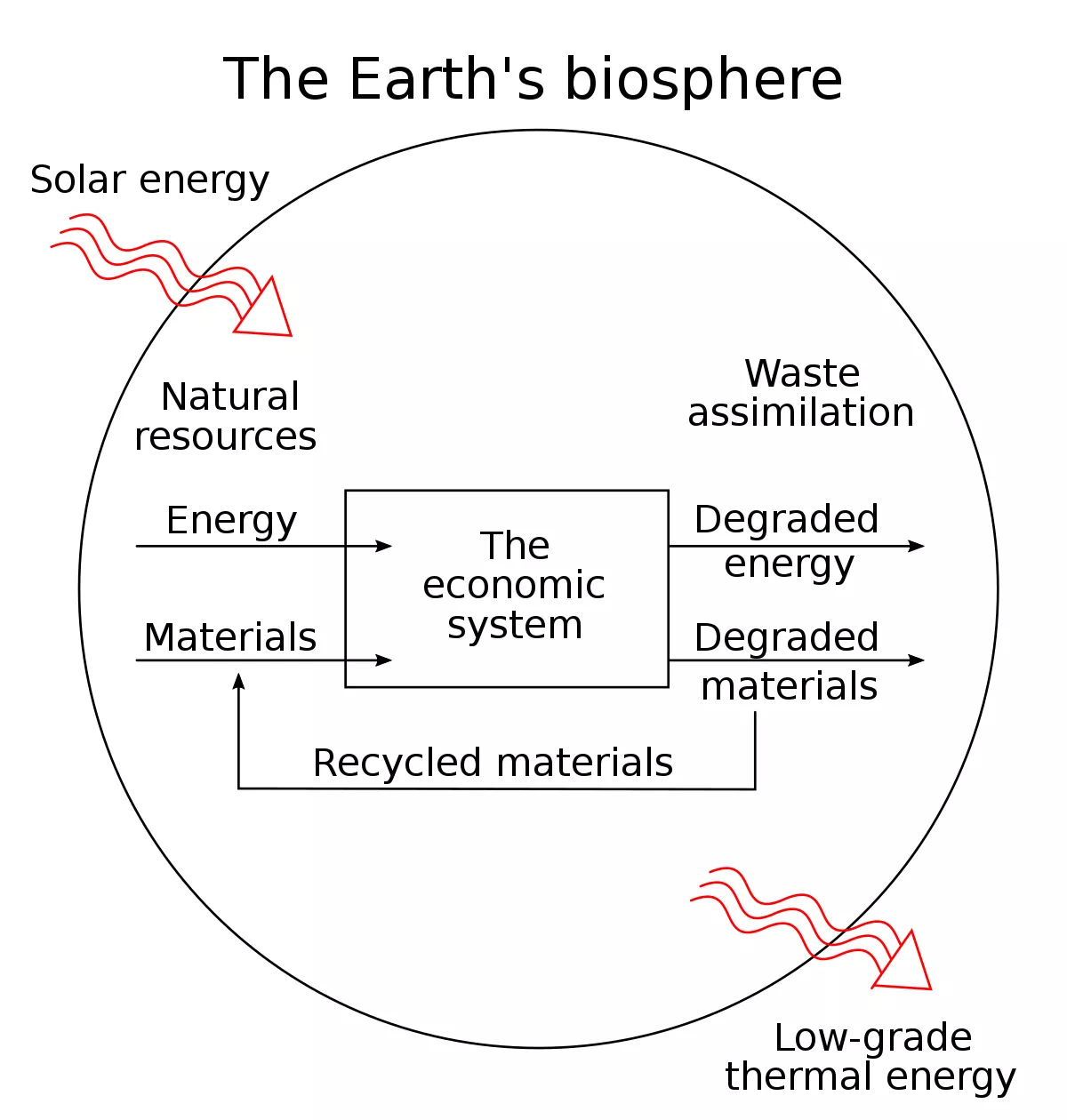

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues that the relevance of thermodynamics to economics stems from the physical fact that man can neither create nor destroy matter or energy, only transform it.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues from this inspiration from cosmology that humanity's economic activities shorten the time frame to planetary heat death, locally on Earth.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen points out that the earth is a closed system in the thermodynamic sense of the term: the earth exchanges energy, but not matter with the rest of the universe.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues that this 'asymmetry' helps explain the historical subjection of the countryside by the town since the dawn of civilisation, and he criticises Karl Marx for not taking this subjection properly into account in his theory of historical materialism.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen cautions that this situation is a major reason why the carrying capacity of earth is decreasing.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen realised that production cannot be adequately described by stocks of equipment and inventories only, or by flows of inputs and outputs only.

Contrary to neoclassical production theory, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen identifies nature as the exclusive primary source of all factors of production.

Later, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen introduced the term 'bioeconomics' to describe his view that man's economic struggle is a continuation of the biological struggle.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen did manage to write a sketch on it, though.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen takes a dismal view on human nature and the future of mankind.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's point is that only material resources can be transformed into man-made capital.

Contrary to the neoclassical position, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues that flow factors and fund factors are essentially complementary, since both are needed in the economic process in order to have a working economy.

However, contrary to the widely established use of Turner's simplifying taxonomy, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen never referred to his own position as 'strong sustainability' or any other variant of sustainability.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen flatly dismissed any notion of sustainable development as only so much 'snake oil' intended to deceive the general public.

In several articles, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen criticised his student's concept of a steady-state economy.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues that Daly's steady-state economy will provide no ecological salvation for mankind, especially not in the longer run.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen argues that the first viable technology in human history was fire.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen believed that for a worldwide solar-powered economy to be truly energy self-supporting, a Promethean kind of solar collector had yet to be invented.

Later, some scholars have argued that the efficiency of solar collectors has increased considerably since Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen made these assessments.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen stressed the point that even with the proliferation of solar collectors throughout the surface of the globe, or the advent of fusion power, or both, any industrial economy will still depend on a steady flow of material resources extracted from the crust of the earth, notably metals.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen repeatedly argued his case that in the future, it will be scarcity of terrestrial material resources, and not of energy resources, that will prove to impose the most binding constraint on man's economy on earth.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's work was blemished somewhat by mistakes caused by his insufficient understanding of the physical science of thermodynamics.

Later, when Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen realised his mistake, his reaction passed through several stages of contemplation and refinement, ultimately leading to his formulation of a new physical law, namely the fourth law of thermodynamics.

The purpose of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's proposed fourth law was to substantiate his initial claim that not only energy resources, but material resources, are subject to general and irreversible physical degradation when put to use in economic activity.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen himself was not confident about this tentative solution to the problem.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen remained embarrassed that he had misinterpreted, and consequently, overstretched the proper application of the physical law that formed part of the title of his magnum opus.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen conceded that he had entered into the science of thermodynamics as something of a bold novice.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen found consolation in the belief that the concept of 'matter dissipation' used by a physicist of Planck's authoritative standing would decisively substantiate his own fourth law and his own concept of material entropy.

In effect, complete and perpetual recycling of material resources will be possible in a future spaceship economy of this kind specified, thereby rendering obsolete Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's proposed fourth law of thermodynamics, Ayres submits.

In ecological economics, Ayres' contribution vis-a-vis Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's proposed fourth law was since described as yet another instance of the so-called 'energetic dogma': Earlier, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen had attached the label 'energetic dogma' to various theorists holding the view that only energy resources, and not material resources, are the constraining factor in all economic activity.

Each year since 1987, the Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen Prize has been awarded by the Southern Economic Association for the best academic article published in the Southern Economic Journal.