1.

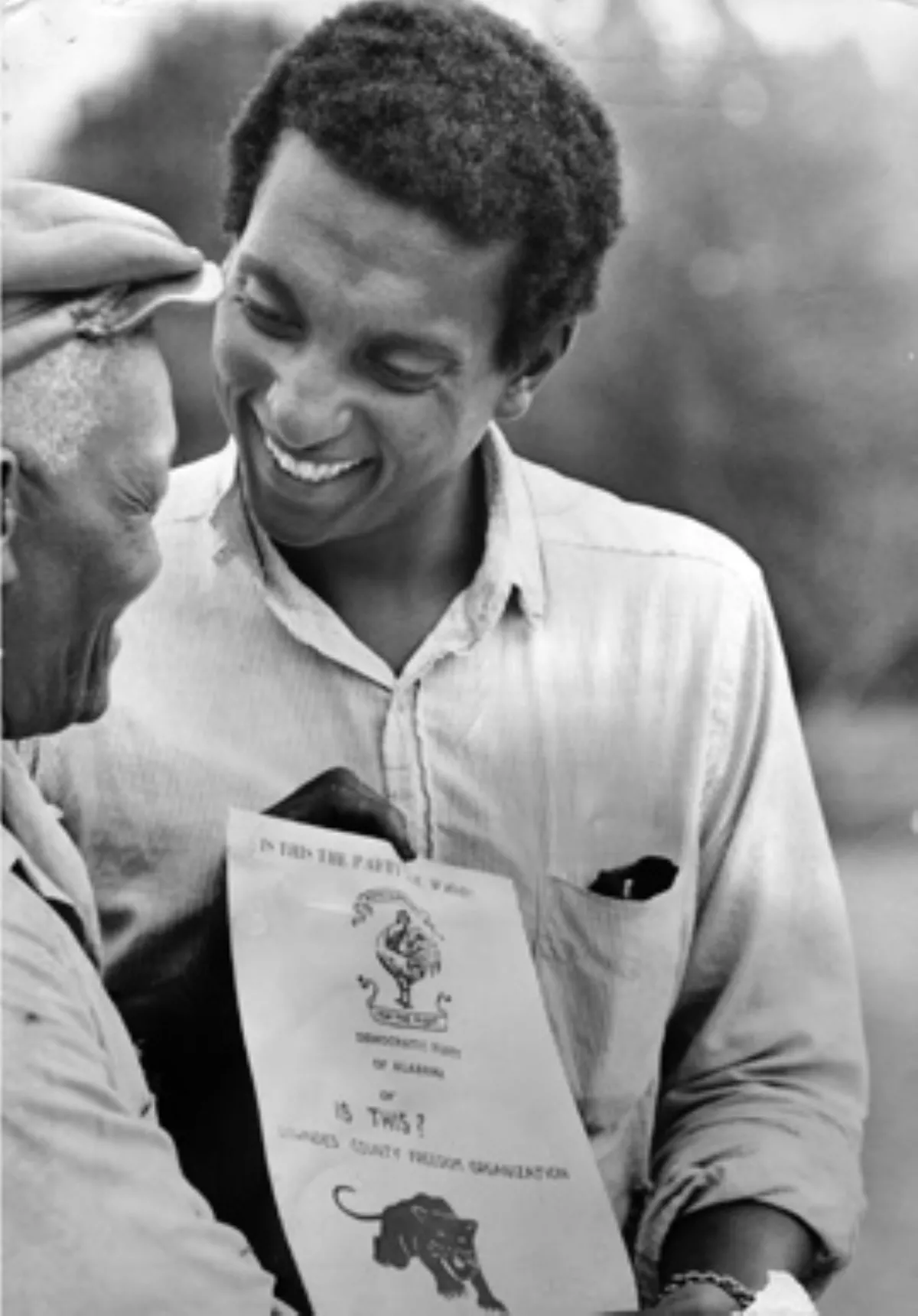

1. Stokely Carmichael was a key leader in the development of the Black Power movement, first while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, then as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party, and last as a leader of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party.