1.

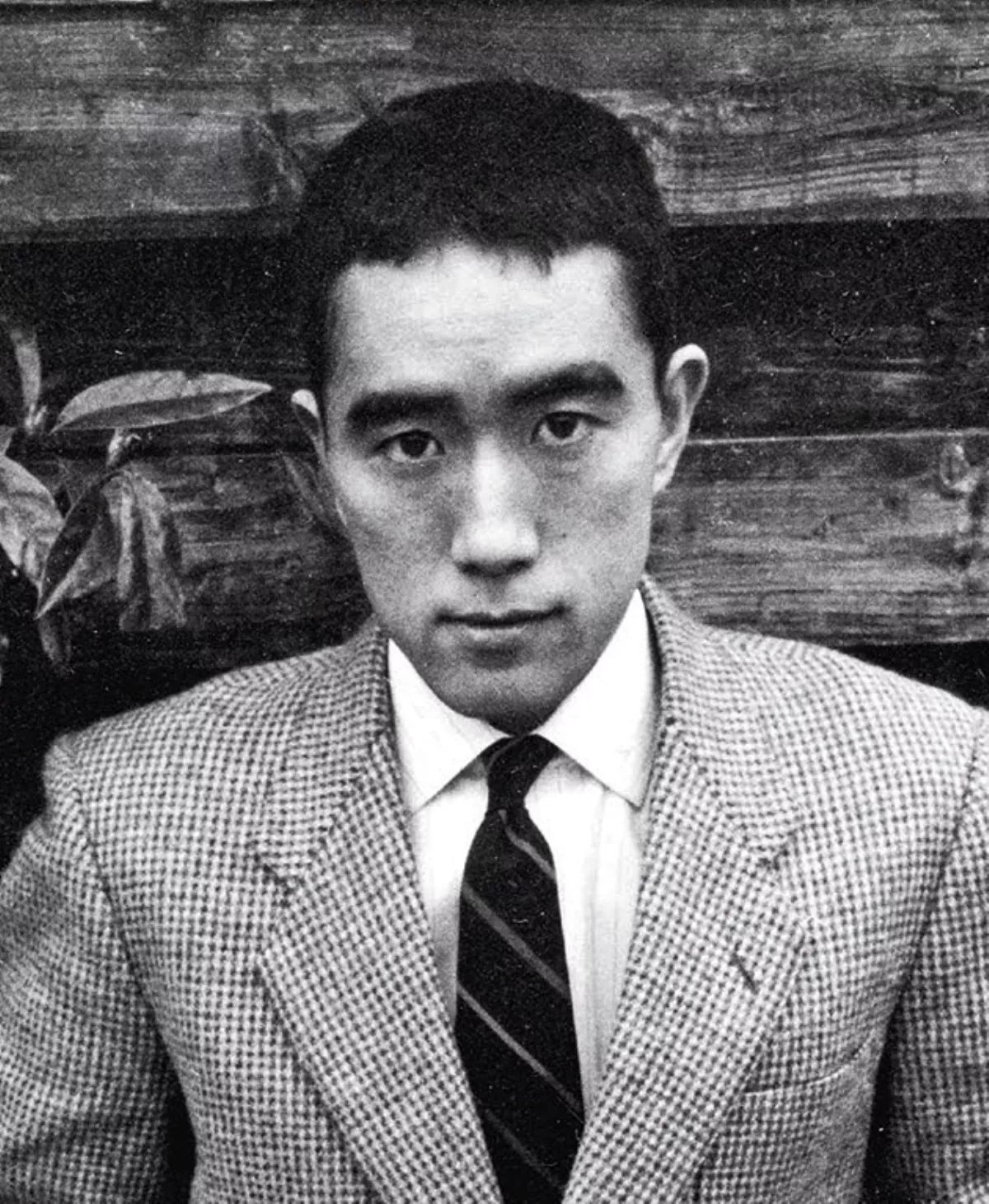

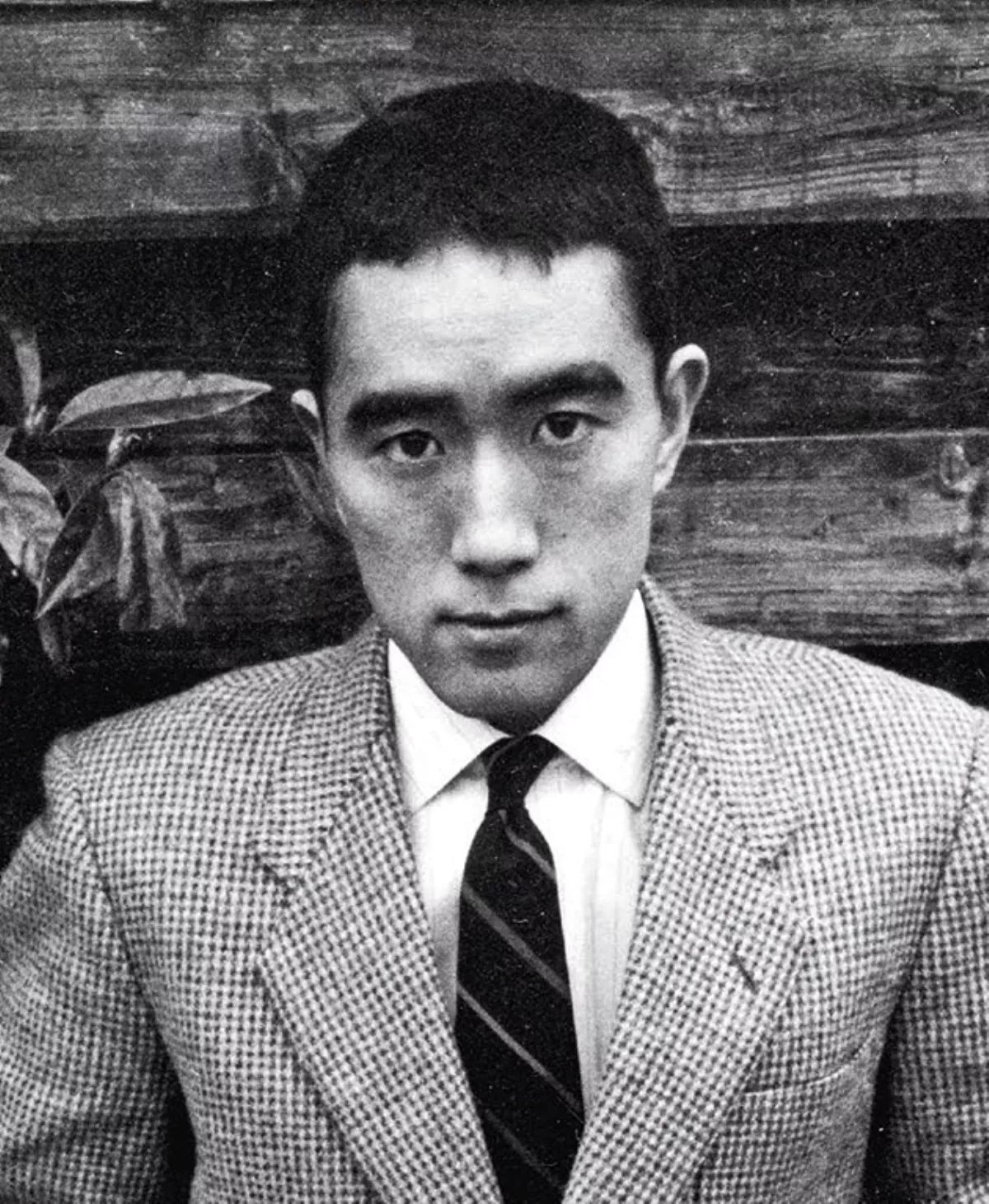

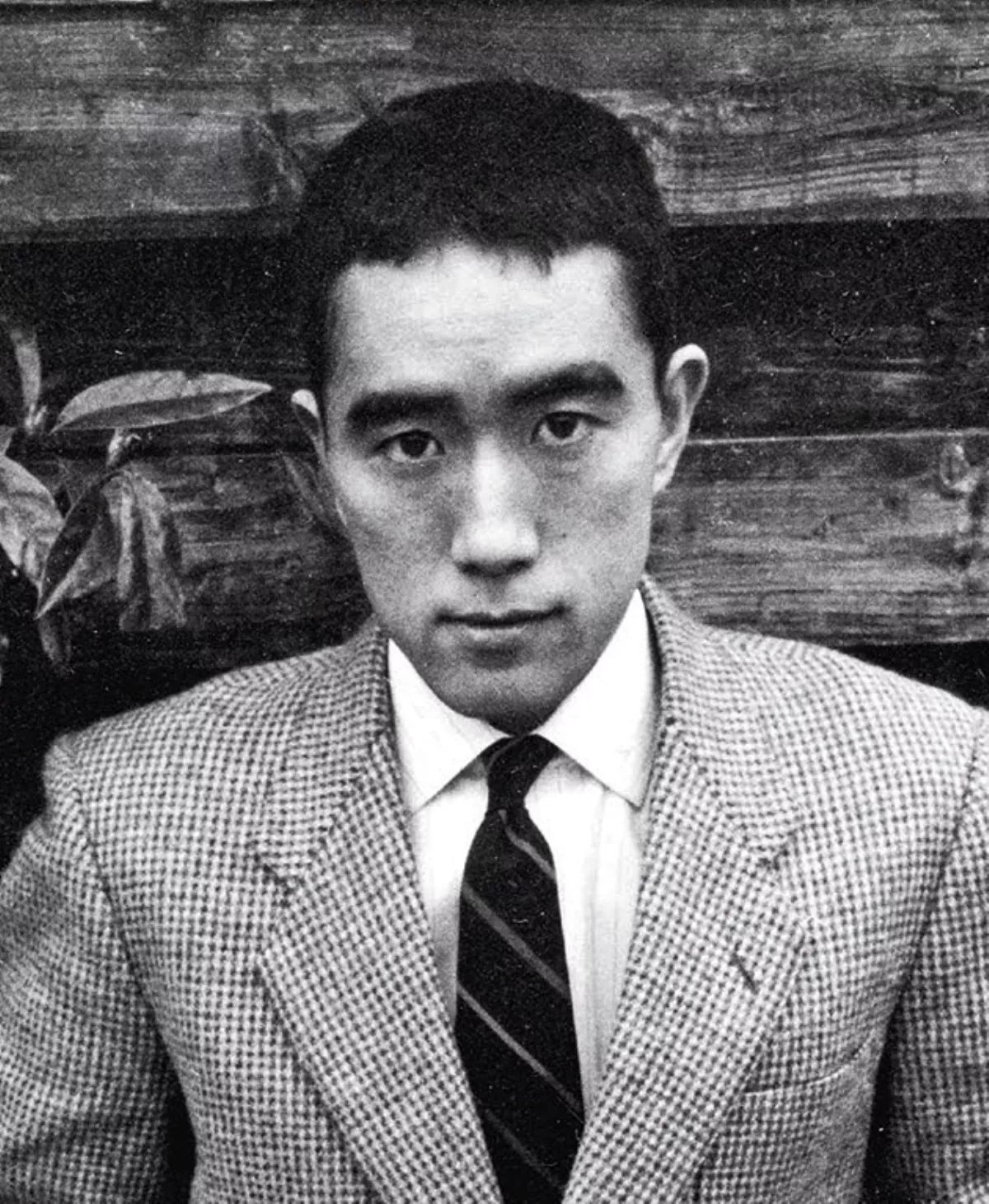

1. Kimitake Hiraoka, known by his pen name Yukio Mishima, was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, ultranationalist, and the leader of an attempted coup d'etat that culminated in his seppuku.

1.

1. Kimitake Hiraoka, known by his pen name Yukio Mishima, was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, ultranationalist, and the leader of an attempted coup d'etat that culminated in his seppuku.

Yukio Mishima's works include the novels Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the autobiographical essay Sun and Steel.

Yukio Mishima's work is characterized by "its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death", according to the author Andrew Rankin.

Yukio Mishima extolled the traditional culture and spirit of Japan, and opposed what he saw as Western-style materialism, along with Japan's postwar democracy, globalism, and communism, worrying that by embracing these ideas the Japanese people would lose their "national essence" and distinctive cultural heritage to become a "rootless" people.

In 1968 Yukio Mishima formed the Tatenokai, a private militia, for the purpose of protecting the dignity of the emperor as a symbol of national identity.

On 14 January 1925, Yukio Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of Tokyo City.

Yukio Mishima's father was Azusa Hiraoka, a government official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce.

Yukio Mishima received his birth name Kimitake in honor of Furuichi Koi who was a benefactor of Sadataro.

Yukio Mishima had a younger sister, Mitsuko, who died of typhus in 1945 at the age of 17, and a younger brother, Chiyuki.

Yukio Mishima's childhood home was a rented house, though a fairly large two-floor house that was the largest in the neighborhood.

Yukio Mishima lived with his parents, siblings and paternal grandparents, as well as six maids, a houseboy, and a manservant.

Yukio Mishima was the granddaughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka, the daimyo of Shishido, which was a branch domain of Mito Domain in Hitachi Province; therefore, Mishima was a descendant of the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu, through his grandmother.

Yukio Mishima did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, engage in any kind of sport, or play with other boys.

Yukio Mishima spent much of his time either alone or with female cousins and their dolls.

When Yukio Mishima was returned to his immediate family at the age of 12, Azusa employed extreme parenting tactics, such as holding young Yukio Mishima up close to the side of a speeding steam locomotive.

Yukio Mishima raided his son's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature, and often ripped his son's manuscripts apart.

When Yukio Mishima was 13, Natsuko took him to see his first Kabuki play: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, an allegory of the story of the 47 Ronin.

Yukio Mishima was later taken to his first Noh play by his maternal grandmother Tomi Hashi.

Yukio Mishima began attending performances every month and grew deeply interested in these traditional Japanese dramatic art forms.

Yukio Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite Gakushuin, the Peers' School in Tokyo, which had been established in the Meiji period to educate the Imperial family and the descendants of the old feudal nobility.

Yukio Mishima was particularly drawn to the works of Japanese poet Shizuo Ito, Haruo Sato, and Michizo Tachihara, who inspired Yukio Mishima's appreciation of classical Japanese waka poetry.

In 1941, at the age of 16, Yukio Mishima was invited to write a short story for the Hojinkai-zasshi, where he submitted Forest in Full Bloom, a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live on within him.

Yukio Mishima sent a copy of the manuscript to his teacher Fumio Shimizu, who was so impressed that he and his fellow editorial board members decided to publish it in their literary magazine Bungei Bunka.

The name "Yukio Mishima" came from yuki, the Japanese word for "snow", because of the snow they saw on Mount Fuji as the train passed.

Yukio Mishima had it published as a keepsake to remember him by, as he assumed that he would die in the war.

Yukio Mishima is much younger than we are, but has arrived on the scene already quite mature.

Later in 1941, Yukio Mishima wrote an essay about his deep devotion to Shinto, titled The Way of the Gods.

On 9 September 1944, Yukio Mishima graduated Gakushuin High School at the top of the class, becoming a graduate representative.

Emperor Hirohito was present at the graduation ceremony, with Yukio Mishima later receiving a silver watch from him at the Imperial Household Ministry.

On 27 April 1944, during the final years of World War II, Yukio Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army, barely passing his conscription examination on 16 May 1944 with a less desirable rating of "second class" conscript.

Yukio Mishima had a cold during his medical check on convocation day, which the army doctor misdiagnosed as tuberculosis; Yukio Mishima was consequently declared unfit for service and sent home.

The veracity of this account is impossible to know for certain, but what is unquestionable is that Yukio Mishima did not speak out against the doctor's diagnosis of tuberculosis.

The unit that Yukio Mishima would have enlisted in was eventually sent to the Philippines, with few survivors.

Yukio Mishima expressed an admiration for kamikaze pilots and other "special attack" units.

Yukio Mishima was deeply affected by Emperor Hirohito's radio broadcast announcing Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945, vowing to protect Japanese cultural traditions and to help to rebuild Japanese culture after the destruction of the war.

Yukio Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946.

On 23 October 1945, Yukio Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from typhoid fever after drinking untreated water.

Yukio Mishima used these events as inspiration and motivation for his later literary work.

Yukio Mishima was worried that his son would become a professional novelist, preferring instead that his son follow in the footsteps of himself and Mishima's grandfather Sadataro and become a bureaucrat.

Yukio Mishima obtained a position in the Ministry of the Treasury and was set for a promising career as a government bureaucrat.

However, after just one year of employment, Yukio Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to allow him to resign from his post and devote himself to writing full time.

In 1945, Yukio Mishima began the short story "A Story at the Cape" and continued to work on it throughout World War II.

Yukio Mishima had heard that the famed writer Yasunari Kawabata had praised his work before the end of the war.

Uncertain of who else to turn to, Yukio Mishima took the manuscripts for The Middle Ages and The Cigarette with him, visited Kawabata in Kamakura, and asked for his advice and assistance in January 1946.

In 1946, Yukio Mishima began his first novel, Thieves, a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide.

Around 1949, Yukio Mishima published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in Modern Literature.

Yukio Mishima visited Greece during his travels, a place which had fascinated him since childhood.

Yukio Mishima's visit to Greece became the basis for his 1954 novel The Sound of Waves, which drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe.

Yukio Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works.

In 1959, Yukio Mishima published the artistically ambitious novel Kyoko no Ie.

Until 1960, Yukio Mishima had not written works that were seen as especially political.

In June 1960, at the climax of the protest movement, Yukio Mishima wrote a commentary in the Mainichi Shinbun newspaper, entitled "A Political Opinion".

Yukio Mishima warned against the dangers of the Japanese people following ideologues who told lies with honeyed words.

The next year, Yukio Mishima published The Frolic of the Beasts, a parody of the classical Noh play Motomezuka, written in the 14th-century by playwright Kiyotsugu Kan'ami.

In 1962, Yukio Mishima produced his most artistically avant-garde work Beautiful Star, which at times comes close to science fiction.

In 1965, Yukio Mishima wrote the play Madame de Sade that explores the complex figure of the Marquis de Sade, traditionally upheld as an exemplar of vice, through a series of debates between six female characters, including the Marquis' wife, the Madame de Sade.

Yukio Mishima's play was inspired in part by his friend Tatsuhiko Shibusawa's 1960 Japanese translation of the Marquis de Sade's novel Juliette and a 1964 biography Shibusawa wrote of de Sade.

Yukio Mishima was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963,1964,1965,1967 and 1968, and was a favorite of many foreign publications.

However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Yukio Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim.

Yukio Mishima was an actor, and starred in Yasuzo Masumura's 1960 film, Afraid to Die, for which he sang the theme song.

Yukio Mishima performed in films like Patriotism or the Rite of Love and Death directed by himself, 1966, Black Lizard directed by Kinji Fukasaku, 1968 and Hitokiri directed by Hideo Gosha, 1969.

Yukio Mishima was featured as the photo model in the photographer Eikoh Hosoe's book Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses, as well as in Tamotsu Yato's photobooks Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan and Otoko: Photo Studies of the Young Japanese Male.

The American author Donald Richie gave an eyewitness account of seeing Yukio Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yato's photoshoots.

At that time in the late 1960s, Yukio Mishima was the first celebrity to be described as a "superstar" by the Japanese media.

In 1955, Yukio Mishima took up weight training to overcome his weak constitution, and his strictly observed workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life.

Yukio Mishima later became very skilled at kendo, and became 2nd Dan in battojutsu, and 1st Dan in karate.

Yukio Mishima hoped to marry her, but they broke up in 1957.

In February 1961, Yukio Mishima became embroiled in the aftermath of the Shimanaka incident.

Yukio Mishima argued that it was the custom of traditional Japanese patriots to immediately commit suicide after committing an assassination.

Yukio Mishima wrote a play titled The Harp of Joy, but star actress Haruko Sugimura and other Communist Party-affiliated actors refused to perform because the protagonist held anti-communist views and mentioned criticism about a conspiracy of world communism in his lines.

When Neo Litterature Theatre experienced a schism in 1968, Yukio Mishima formed another troupe, the Roman Theatre, and worked with Matsuura and Nakamura again.

Yukio Mishima had eagerly anticipated the long-awaited return of the Olympics to Japan after the 1940 Tokyo Olympics were cancelled due to Japan's war in China.

Yukio Mishima hated Ryokichi Minobe, who was a socialist and the governor of Tokyo beginning in 1967.

Yukio Mishima was fond of manga and gekiga, especially the drawing style of Hiroshi Hirata, a mangaka best known for his samurai gekiga; the slapstick, absurdist comedy in Fujio Akatsuka's Moretsu Ataro; and the imaginativeness of Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitaro.

Yukio Mishima especially loved reading the boxing manga Ashita no Joe in Weekly Shonen Magazine every week.

Yukio Mishima was a fan of science fiction, contending that "science fiction will be the first literature to completely overcome modern humanism".

Yukio Mishima praised Arthur C Clarke's Childhood's End in particular.

Yukio Mishima traveled to Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula with his wife and children every summer from 1964 onwards.

In Shimoda, Yukio Mishima often enjoyed eating local seafood with his friend Henry Scott-Stokes.

Yukio Mishima liked ordinary American people after the war, and he and his wife had even visited Disneyland as newlyweds.

In February 1967, Yukio Mishima joined his fellow-authors Yasunari Kawabata, Kobo Abe, and Jun Ishikawa in issuing a statement condemning China's Cultural Revolution for suppressing academic and artistic freedom.

Yukio Mishima traveled widely and met with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and President Zakir Hussain.

Yukio Mishima left extremely impressed by Indian culture, and what he felt was the Indian people's determination to resist Westernization and protect traditional ways.

Yukio Mishima feared that his fellow Japanese were too enamored of modernization and Western-style materialism to protect traditional Japanese culture.

On his way home from India, Yukio Mishima stopped in Thailand and Laos; his experiences in the three nations became the basis for portions of his novel The Temple of Dawn, the third in his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility.

Yukio Mishima praised the Hagakure, a treatise on warrior virtues authored by the samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo during the Edo period that valorized the warrior's willingness to die, as being at the core of his literary production and "the source of his vitality as a writer".

In On the Defense of Culture, Yukio Mishima preached the centrality of the emperor to Japanese culture, and argued that Japan's postwar era was a time of flashy but ultimately hollow prosperity, lacking any truly transcendent literary or poetic talents comparable to the 18th century masters of the original Genroku era, such as the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon or the poet Matsuo Basho.

In 1968, Yukio Mishima wrote a play titled My Friend Hitler, in which he depicted the historical figures of Adolf Hitler, Gustav Krupp, Gregor Strasser, and Ernst Rohm as mouthpieces to express his own views on fascism and beauty.

Yukio Mishima explained that after writing the all-female play Madame de Sade, he wanted to write a counterpart play with an all-male cast.

Yukio Mishima thoroughly lacked the refreshing, sunny quality indispensable to becoming a hero.

Yukio Mishima showed his sincerity by signing his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, in his own blood.

On 13 May 1969, Yukio Mishima accepted an invitation to debate with members of the Tokyo University Zenkyoto on the university's Komaba campus.

At this debate, Yukio Mishima told the students, "As long as you refer to the Emperor as 'Emperor,' I will gladly join forces with you," but in the end the ideological differences between Yukio Mishima and the students could not be overcome.

Yukio Mishima aimed for a very long novel with a completely different raison d'etre from Western chronicle novels of the 19th and 20th centuries; rather than telling the story of a single individual or family, Yukio Mishima boldly set his goal as interpreting the entire human world.

Yukio Mishima hoped to express in literary terms something akin to pantheism.

From 12 April to 27 May 1967, Yukio Mishima underwent basic training with the Ground Self-Defense Force.

Yukio Mishima had originally lobbied to train with the GSDF for six months, but was met with resistance from the Defense Agency.

Accordingly, Yukio Mishima trained under his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, and most of his fellow soldiers did not recognize him.

From June 1967, Yukio Mishima became a leading figure in a plan to create a 10,000-man "Japan National Guard" as a civilian complement to the Self-Defense Forces.

Yukio Mishima began leading groups of right-wing college students to undergo basic training with the GSDF in the hope of training 100 officers to lead the National Guard.

Yukio Mishima accepted no outside money, and funded the activities of the Tatenokai using royalties from his writing.

Yukio Mishima wore a white hachimaki headband with a red hinomaru circle in the center bearing the kanji for "To be reborn seven times to serve the country", a reference to the last words of Kusunoki Masasue, the younger brother of the 14th-century imperial loyalist samurai Kusunoki Masashige, as the two brothers died fighting to defend the emperor.

Yukio Mishima's speech was intended to inspire a coup d'etat to restore direct rule to the emperor.

Yukio Mishima succeeded only in irritating the soldiers, and was heckled, with jeers and the noise of helicopters drowning out some parts of his speech.

Morita had been assigned to serve as Yukio Mishima's second, cutting off his head with a sword at the end of the rite to spare him unnecessary pain.

However, Yukio Mishima attempted to dissuade them and three of the members acquiesced to his wishes.

Yukio Mishima had planned his suicide meticulously for at least a year, with no one outside a small group of hand-picked Tatenokai members knowing of his plans.

Yukio Mishima had made sure his affairs were in order and left money for the legal defense of the three surviving Tatenokai members involved in the incident.

Yukio Mishima had arranged for a department store to send his two children Christmas gifts every year until they became adults, and had asked a publisher to pay the long-term subscription fee for children's magazines in advance and deliver them every month.

Yukio Mishima's remains were returned to his family the day after the incident, and were buried in the grave of the Hiraoka Family at Tama Cemetery on what would have been his 46th birthday, 14 January 1971.

Yukio Mishima has been recognized as one of the world's most important literary persons of the 20th century.

Yukio Mishima wrote 34 novels, approximately 50 plays and 25 books of short stories, more than 35 books of essays, plus a libretto and one film.

The annual Yukio Mishima Prize was established in 1998 by the literary publisher Shinchosha to recognise groundbreaking Japanese literature.

The Yukio Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of "New Right" groups in Japan, such as the "Issuikai", founded by Tsutomu Abe, who was one of Tatenokai members and Yukio Mishima's follower.

The Mishima Yukio Shrine was built in the suburb of Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on 9 January 1983.

Yukio Mishima wrote a detailed account of the whole process, in which the particulars regarding costume, shooting expenses and the film's reception are delved into.