1.

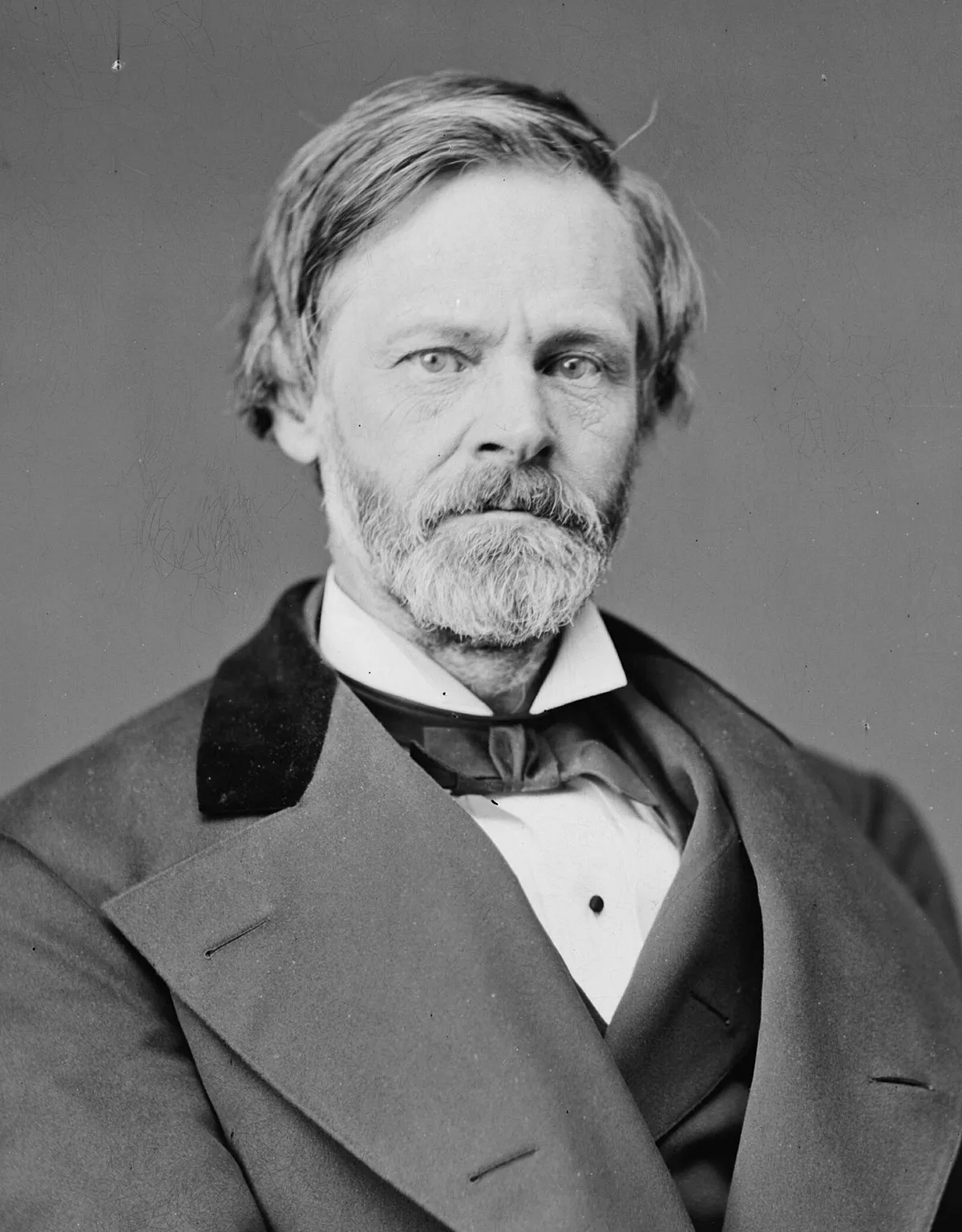

1. John Sherman was an American politician from Ohio who served in federal office throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century.

1.

1. John Sherman was an American politician from Ohio who served in federal office throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century.

John Sherman served as Secretary of the Treasury and Secretary of State.

John Sherman was the younger brother of Union general William Tecumseh Sherman, with whom he had a close relationship.

John Sherman served three terms in the House of Representatives.

John Sherman rose in party leadership and was nearly elected Speaker in 1859.

John Sherman served as the Chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee during his 32 years in the Senate.

John Sherman returned to the Senate after his term expired, serving there for a further sixteen years.

John Sherman was the principal author of the John Sherman Antitrust Act, which was signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890.

John Sherman died at his home in Washington, DC, in 1900 at age 77.

John Sherman's father died suddenly in 1829, leaving his mother to care for 11 children.

The elder John Sherman intended for his namesake to study there until he was ready to enroll at nearby Kenyon College, but Sherman disliked school and was, in his own words, "a troublesome boy".

John Sherman continued his education there at a local academy where, after being briefly expelled for punching a teacher, he studied for two years.

In 1837, John Sherman left school and found a job as a junior surveyor on construction of improvements to the Muskingum River.

John Sherman was admitted to the bar in 1844 and joined his brother's firm.

John Sherman quickly became successful at the practice of law, and by 1847 had accumulated property worth $10,000 and was a partner in several local businesses.

In 1848, John Sherman married Margaret Cecilia Stewart, the daughter of a local judge.

Around the same time, John Sherman began to take a larger role in politics.

Four years later, John Sherman was a delegate to the Whig National Convention where the eventual winner Zachary Taylor was nominated.

In 1852, John Sherman was again a delegate to the Whig National Convention, where he supported the eventual nominee, Winfield Scott, against rivals Daniel Webster and incumbent Millard Fillmore, who had become president following Taylor's death.

John Sherman moved north to Cleveland in 1853 and established a law office there with two partners.

Two months after the Act's passage, John Sherman became a candidate for Ohio's 13th congressional district.

Democrats were defeated across Ohio that year, and John Sherman was elected by 2,823 votes.

John Sherman spent two months in the territory and was the primary author of the 1,188-page report filed on conditions there when they returned in April 1856.

In spite of this defeat John Sherman had achieved considerable prominence for a freshman representative.

John Sherman spoke against the Kansas bill in the House, pointing out the evidence of fraud in the elections there.

John Sherman's speech attracted attention and was the start of Sherman's focus on financial matters, which would continue throughout his long political career.

Again, sectional tension had increased while Congress was in recess, this time due to John Sherman Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Southerners accused John Sherman of having endorsed the book, but he protested that he had only endorsed its use as a campaign tool and had never read it.

Pennington assigned John Sherman to serve as chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means, where he spent much of his time on appropriations bills, while cooperating with his colleague Justin Smith Morrill on the passage of what became known as the Morrill Tariff.

John Sherman spoke in favor of the bill, and it passed the House by a vote of 105 to 64.

Likewise, John Sherman supported a bill admitting Kansas as a free state that passed in 1861.

John Sherman was renominated for Congress in 1860 and was active in Abraham Lincoln's campaign for president, giving speeches on his behalf in several states.

John Sherman returned to Washington for the lame duck session of the 36th Congress.

John Sherman voted for the amendment, which passed both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification.

John Sherman took his seat on March 23,1861, as the Senate had been called into special session to deal with the secession crisis.

Lincoln soon called for 75,000 men to enlist for three months to put down the rebellion, which William John Sherman thought too few and too short a duration.

William's thoughts on the war greatly influenced his brother, and John Sherman returned home to Ohio to encourage enlistment, briefly serving as an unpaid colonel of Ohio Volunteers.

The Civil War expenditures quickly strained the government's already fragile financial situation and John Sherman, assigned to the Senate Finance Committee, was involved in the process of increasing the revenue.

John Sherman endorsed the measure, and even spoke in favor of a steeper tax than the one imposed by the Act, preferring to raise revenue by taxation than by borrowing.

John Sherman defended his position as necessary in his memoirs, saying "from the passage of the legal tender act, by which means were provided for utilizing the wealth of the country in the suppression of the rebellion, the tide of war turned in our favor".

John Sherman agreed with Chase wholeheartedly and hoped that state banking would be eliminated.

John Sherman believed the state-by-state system of regulation was disorderly and unable to facilitate the level of borrowing a modern nation might require.

Besides his role in financial matters, John Sherman participated in debate over the conduct of the war and goals for the post-war nation.

John Sherman voted for the Confiscation Act of 1861, which allowed the government to confiscate any property being used to support the Confederate war effort and for the act abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia.

John Sherman voted for the Confiscation Act of 1862, which clarified that slaves "confiscated" under the 1861 Act were freed.

In 1864, John Sherman voted for the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery.

Sherman and Johnson had been friendly, and some observers hoped that Sherman could serve as a liaison between Johnson and the party's "Radical" wing.

That same year, John Sherman voted for the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection of the laws to the freedmen.

The 40th Congress's lame duck session passed the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed that the right to vote could not be restricted because of race; John Sherman joined the two-thirds majority that voted for its passage.

John Sherman voted in favor of both Acts, which had Grant's support.

John Sherman instead favored leaving the existing notes in circulation and letting the growth in population catch up to the growth in money supply.

John Sherman suggested an amendment that would instead just allow the Treasury to redeem the notes for lower-interest bonds, now that the government's borrowing costs had decreased.

John Sherman's amendment was voted down, and the Contraction Act passed; greenbacks would be gradually withdrawn, but those still circulating would be redeemable for the high-interest bonds as before.

John Sherman continued to favor wider circulation of the greenback when he voted for the Currency Act of 1870, which authorized an additional $54 million in United States Notes.

John Sherman was involved in debate over the Funding Act of 1870.

The Funding Act, which John Sherman called "[t]he most important financial measure of that Congress," refunded the national debt.

The bill as John Sherman wrote it authorized $1.2 billion of low-interest rate bonds to be used to purchase the high-rate bonds issued during the war, to take advantage of the lower borrowing costs brought about by the peace and security that followed the Union victory.

John Sherman returned to his leadership of the Finance Committee, and the issues of greenbacks, gold, and silver continued into the next several congresses.

John Sherman emphasized in his memoirs that the bill was openly debated for several years and passed both Houses with overwhelming support and that, given the continued circulation of smaller silver coins at the same 16:1 ratio, nothing had been "demonetized," as his opponents claimed.

The idea of withdrawing the greenbacks from circulation altogether had been tried and quickly rejected in 1866; the notes were, as John Sherman said, "a great favorite of the people".

Still, John Sherman desired an eventual return to a single circulating medium: gold.

Hayes and John Sherman became close friends in the next four years, taking regular carriage rides together to discuss matters of state in private.

John Sherman knew that silver was gaining popularity, and opposing it might harm the party's candidates in the 1880 elections, but he agreed with Hayes in wanting to avoid inflation.

John Sherman thought Hayes should sign the amended bill but did not press the matter, and the President vetoed it.

John Sherman was not a civil service reformer, but he went along with Hayes's instructions.

John Sherman agreed with Hayes that the three had to resign, but he made clear in a letter to Arthur that he had no personal grudge against the Collector.

John Sherman submitted appointments to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements but the Senate's Commerce Committee, which Conkling chaired, voted unanimously to reject the nominees.

When Congress reconvened, John Sherman pressured his former Senate colleagues to confirm the President's replacement nominees, which they did after considerable debate.

John Sherman replied that it was important that the Republican party win the election there, despite their intra-party differences.

Hayes's preference was for John Sherman to succeed him, but he made no official endorsement, and he did not think John Sherman could win the nomination.

John Sherman held out hope that he would be that compromise candidate, but while his vote tally reached as high as 120, he never commanded even all of Ohio's delegates.

John Sherman's divided home-state support was likely fatal to his cause, as Blaine delegates, searching for a new champion, did not think Sherman would make a popular candidate.

John Sherman was respected among his fellow Republicans for his intelligence and hard work, but there were always doubts about his potential as a national candidate.

John Sherman continued at the Treasury for the rest of Hayes's term, leaving office March 3,1881.

John Sherman rejoined the Finance Committee, but Justin Smith Morrill, his old House colleague, now held the chairmanship.

When John Sherman re-entered the Senate in the 47th United States Congress, the Republicans were not in the majority.

John Sherman sided with Garfield on the appointments and was pleased when the New York legislature declined to reelect Conkling and Platt, replacing them with two less troublesome Republicans.

John Sherman spoke on behalf of Ohio Governor Charles Foster's effort for a second term and went to Kenyon College with ex-President Hayes, where he received an honorary degree.

John Sherman looked forward to staying with his wife at home for an extended period for the first time in years, when news arrived that Garfield had been shot in Washington.

John Sherman spoke in favor of merit selection and against removing employees from office without cause.

John Sherman was against the idea that civil servants should have unlimited terms of office but believed that efficiency, not political activity, should determine an employee's length of service.

John Sherman supported the bill, more for the excise reduction than for the tariff changes.

John Sherman paid greater attention to foreign affairs during the second half of his Senate career, serving as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations.

John Sherman opposed both the 1880 treaty revisions and the bill Miller proposed, believing that the Exclusion Act reversed the United States' traditional welcoming of all people and the country's dependence on foreign immigration for growth.

President Arthur vetoed the bill, and John Sherman voted to sustain the veto.

John Sherman voted against this bill, too, but it passed, and Arthur signed it into law.

In 1885, John Sherman voted in favor of the Alien Contract Labor Law, which barred engaging in a labor contract before immigrating or transporting a person under such a contract to the United States.

John Sherman saw this Act as a more appropriate solution to depressed wages than Chinese exclusion: the problem, as he saw it, was not the national origin of Chinese immigrants, but their employment under serf-like conditions.

In 1884, John Sherman again ran for the Republican nomination, but his campaign never gained steam.

Blaine gathered support the next day, and John Sherman withdrew after the fourth ballot.

John Sherman returned to the Senate where, in 1885, he was elected President pro tempore of the Senate.

John Sherman encouraged fairness in the treatment of black Americans and denounced their mistreatment at the hands of the "redeemed" Southern state governments.

The tour had its effect, and John Sherman's hopes were high.

John Sherman gained votes on the second ballot, but plateaued there; by the fifth ballot, it was clear that he would gain no more delegates.

John Sherman refused to withdraw, but his supporters began to abandon him; by the eighth ballot, the delegates coalesced around Benjamin Harrison of Indiana and voted him the nomination.

John Sherman thought Harrison was a good candidate and bore him no ill will, but he did begrudge Alger, whom he believed "purchased the votes of many of the delegates from the southern states who had been instructed by their conventions to vote for me".

John Sherman agreed with the general idea of the law, but objected to certain portions, especially a provision that gave state courts jurisdiction over enforcement disputes.

John Sherman believed the law should allow for more nuance as well, insisting that competition against other forms of transit be considered.

The bill Sherman proposed was largely derivative of a failed bill from the previous Congress written by Senator George F Edmunds, which Sherman had amended during its consideration.

Until 1888, John Sherman had shown little interest in the trust question but it was rising in the national consciousness, and John Sherman now entered the fray.

The revised bill John Sherman proposed was simple, stating that "[e]very contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal".

In debate, John Sherman praised the effects of corporations on developing industry and railroads and asserted the right for people to form corporations, so long as they were "not in any sense a monopoly".

The Act was later criticized for its simple language and lack of defined terms, but John Sherman defended it, saying that it drew on common-law language and precedents.

John Sherman denied that the Act was anti-business at all, saying that it only opposed unfair business practices.

John Sherman emphasized that the Act aimed not at lawful competition, but at illegal combination.

John Sherman was elected in 1892 to a sixth term, easily defeating the Democratic candidate in the state legislature.

In 1894, John Sherman surpassed Thomas Hart Benton's record for longest tenure in the Senate.

John Sherman became known as a "friend of England" in Washington DC.

John Sherman frequently made reference to British history in his speeches.

John Sherman believed there was a lot America could learn from England as an example with respects to economic systems, railroads and governance, and he was fond of highlighting the English origins of American political thought.

John Sherman met with John Bright and attended a speech given by Benjamin Disraeli.

John Sherman retired from public life after resigning as Secretary of State.

Except for one day, John Sherman had spent the previous forty-two years, four months, and twenty-two days in government service.

John Sherman gave a few interviews in which he disagreed with the administration's policy of annexing Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

John Sherman continued to alternate between houses in Mansfield and Washington.

John Sherman mostly remained out of politics, except for a letter he wrote endorsing George K Nash for Governor of Ohio in 1899.

John Sherman died at his Washington home on October 22,1900, in the company of his daughter, relatives and friends.

John Sherman was not unmindful of his legacy and left $10,000 in his will for a biography to be written "by some competent person".

John Sherman is most remembered now for the antitrust act that bears his name.

John Sherman was a charter member of the District of Columbia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

John Sherman served as one of the Society's vice presidents from 1891 to 1893.